Americans have had to deal with disaster preparedness for decades, anticipating events such as industrial accidents, power plant meltdowns, natural disasters, and nuclear attacks. Since September 11, 2001, the nation has spent unprecedented resources, created new federal, state, and local agencies, and greatly intensified efforts to prepare for catastrophes. But when Hurricane Katrina hit, we were unable to respond in an organized and comprehensive manner. This does not bode well for how we would be able to respond to significant terrorism attacks or a large-scale industrial accident. We still lack the capacity to imagine what would or could actually happen in a catastrophic scenario.

Scientists and engineers had warned for more than a decade that the levees in New Orleans would fail and that the entire city would be flooded in the event of a sufficiently severe storm. Even so, legislators elected not to fund the repair and stabilization of the increasingly fragile levees. As we have seen, there was seemingly no advance appreciation for the extraordinary challenges of mass evacuation — the management of special populations such as hospital and nursing home patients, the maintenance of social order, and the need for rapid search and rescue missions.

Hurricane Rita gave us a chance to correct some of our mistakes. But there was a series of additional flagrant missteps such as failing to provide fuel for cars stuck in daylong traffic jams and grossly underestimating the number of cars that would be evacuating from Houston and Galveston. There were so many errors of planning and execution that, had Rita been a Category 4 or 5 with a direct hit on Houston, there would have been grave consequences.

It is obvious that we need to reexamine our most basic assumptions about planning for catastrophic events.True, the range of bad scenarios is limitless, and we can’t have detailed plans for all of them. Still, we should consider a series of likelihoods around which we can effectively plan in hopes of establishing general principles that we can apply to other major emergencies. This is the direction in which the Department of Homeland Security is headed. The process will require creativity and imagination, attributes generally difficult to identify in most large bureaucracies.Why are these qualities important? Because when disaster actually occurs, the details — like having adequate fuel, or a contingency plan for what to do with a beloved family pet — become vital issues.

Another issue in disaster response is that the people in charge are often politicians who are not experienced or comfortable with disaster management. Clearly, in order to get elected, politicians need to have the charisma of a successful businessperson or lawyer, but, when they are thrust onto center stage to manage a disaster, the results can be damaging. Mistakes are made. Communications are botched. People lose confidence in the authorities at precisely the wrong time.

Yet it’s not just about individual leaders. There needs to be a lead agency in charge. That agency has to have irrefutable credibility and expertise. There is a growing sense that in high-consequence disasters involving large-scale damage and population risk, the Department of Defense and U.S. military forces should always be the lead agency. No other government entities have equivalent experience, organizational structure, or logistic capacity.

Obviously, in any disaster, there are factors beyond our control. Considering the severity and geographic impact range of 90,000 square miles, it would have been impossible to survive Hurricane Katrina completely unscathed, no matter who was in charge. Nonetheless, survival is greatly affected by the speed and quality of the response.We need to field the most capable agencies working under efficient managerial structure to ensure the best possible outcome. In smaller-scale disasters, relying on local management with “as needed” state assistance usually works. Federal resources are summoned if the governor feels that state assets are insufficient. We need to develop hard, objective criteria for when the federal government will assume responsibility.

The nation cannot afford to depend on the same people who have been responsible for disaster preparedness planning in the past. Government agencies tend to be closed shops — often with little interest in bringing in outsiders. But there should be room at the table for all those who are capable of imaginative, large-scale problem solving, even if they come from disparate backgrounds.

Columbia’s Role

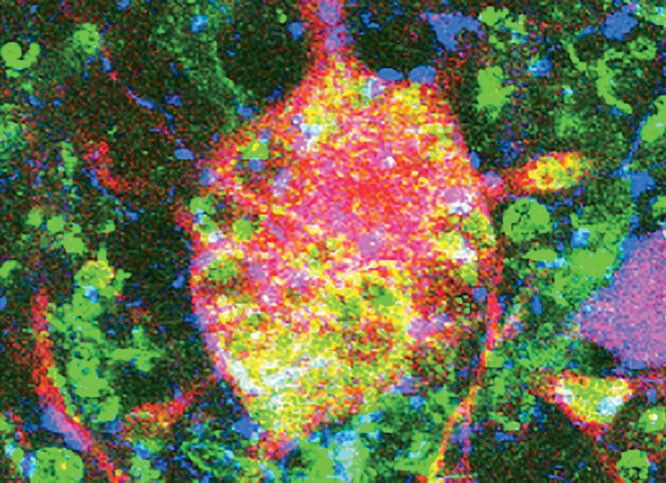

That said, universities have a major role to play in developing the science of disaster preparedness. When I arrived at Columbia in May 2003, we created the National Center for Disaster Preparedness (NCDP).The NCDP’s agenda was to upgrade the capacity of the University and the Mailman School of Public Health (MSPH) to understand what preparedness means and how to provide research information and training. Along with many of our colleagues from other parts of the University, we are focusing on bioterrorism response. The NCDP also been concerned about preparedness for natural disasters such as weather-related events and the pandemic flu.

In addition to research, the NDCP is developing the capacity to respond. Within days of Hurricane Katrina making landfall, we created Operation Assist, a partnership between the NCDP and the Children’s Health Fund (CHF). CHF is a nonprofit organization I founded with the musician Paul Simon in 1987 that provides healthcare access to underserved children around the country. CHF uses more than 20 mobile medical units — essentially custom RVs — to treat disadvantaged children and families in 18 urban and rural communities sites throughout the country.

Operation Assist represents the combined forces of an integrated program of clinical medical care and a strong public health agenda. Four medical teams are operating in Louisiana and Mississippi, with a fifth on the way. Doctors come from a network of CHF affiliates around the country and also from the New York–Presbyterian Hospital community. Robert Bristow, MD, assistant clinical professor of emergency medicine at New York–Presbyterian, is helping to coordinate physicians and medical staff.

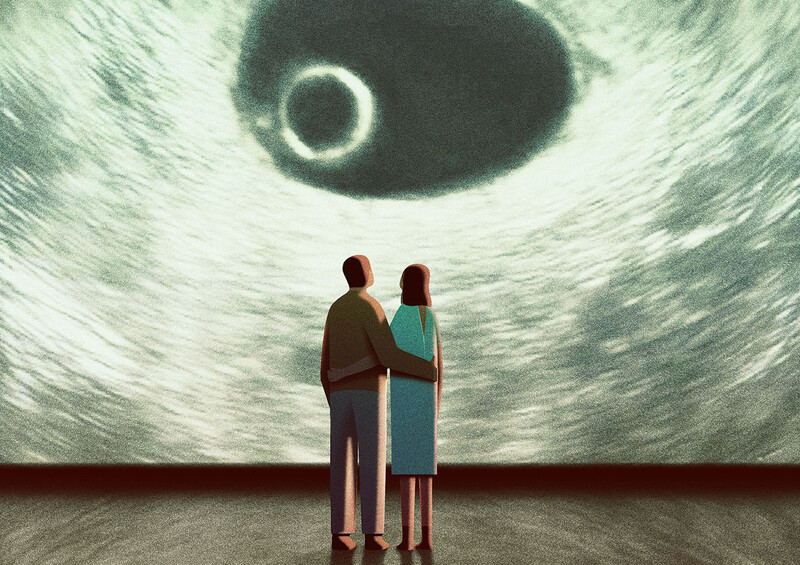

Operation Assist is currently evolving from an acute rescue and emergency medical care model to what we describe as a system of longer-term, disaster-based primary care in very medically underserved communities. We’re still dealing with people who are disoriented, who haven’t been able to get to a doctor, who may be missing prescriptions, and who have chronic illnesses that may not be under control. We are beginning to assess and respond to the mental health needs of a deeply traumatized and displaced population, including children and elderly adults in particular. In addition to the tens of thousands of people with severe preexisting mental health conditions that need to be identified and treated, there are now hundreds of thousands of people who will be affected by the stress of the disaster and the uncertainty of nearterm recovery.They will also need support and rapid restabilization of their lives.This is complicated by the fact that people behind the cleanup effort have also lost homes, jobs, and communities.

Richard Garfield, MD, Henrik H. Bendixen Clinical Professor of International Nursing at Columbia University’s School of Nursing, is the deputy director for the public health aspects of Operation Assist. Under his direction, Operation Assist will conduct needs assessment surveys of schoolchildren, environmental assessment, and the development of guidance materials for families returning to homes in ravaged communities. Additional work will involve the development of programs for children in schools and providing mental health support to affected families. The NCDP faculty and staff involved with these functions include Michael Reilly, program coordinator in the MSPH dean’s office, who is director of training and education of the NCDP. Paula Madrid, MD, program director in MSPH, is the clinical director of the NCDP’s Resiliency Program. Operation Assist will also actively collaborate with Neil Boothby, MD, professor of clinical population and family health, and director of the Program on Forced Migration and Health at MSPH, who has already started groundbreaking work with school systems in Louisiana and Mississippi.

Finally, the NCDP will certainly continue to advocate for extensive rethinking of national and other strategies for disaster preparedness. On this agenda we will seek collaborators from other centers and programs around the U.S.

Facing the Future

Preparedness for terrorism and high-consequence natural events will put enormous stress on the U.S. economy, affect the functioning and structure of government on all levels, and test the nation’s overall level of competence. We face difficult ethical issues of how to ensure equitable distribution of resources among an economically and racially diverse nation. We need to know a lot more about the psychology of fear and resiliency in an age of terrorism and megastorms. We need to know about the historical, social, and political context of preparation for these events.

Many of us were outspoken about the inadequacy of the immediate response to Hurricane Katrina. Unforgivable and lethal errors of omission and commission were made on many levels. Even now, as many weeks have passed, the pace and comprehensiveness of the response remain strikingly insufficient. As you read this, men, women, and children of the Gulf states continue to suffer.That’s why a program of direct assistance, public health intervention, and advocacy for fundamental change makes sense for the NCDP, the Mailman School, and Columbia University as a whole.