On Christmas Eve 1822, Clement Clarke Moore 1798CC, 1829HON, a newly minted professor of Greek and Hebrew literature at General Theological Seminary, permitted himself a flight of whimsy. He was hosting a holiday gathering in his three-story house at what is now West 23rd Street and Ninth Avenue, and at some point in the evening he cleared his throat and began reading a lighthearted poem titled “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” which he had jotted down as a Christmas gift for his six children.

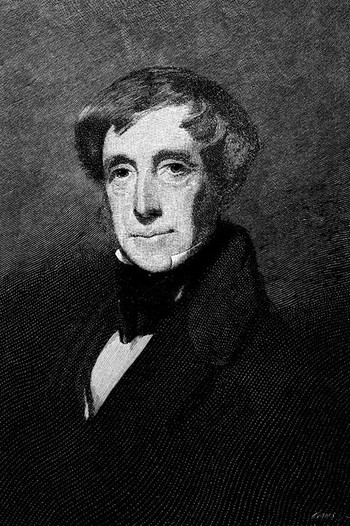

By some accounts, Moore, at forty-three, was an austere man who frowned upon merrymaking and comported himself with a solemnity befitting a Christian man of letters and the steward of his family’s thirty-acre Manhattan estate. His father, Benjamin Moore 1788KC, 1789CC, 1789HON, had been president of Columbia College and bishop of the Protestant Episcopal Church of New York, and in 1804 had administered holy communion to Alexander Hamilton 1788HON, who lay mortally wounded in a house in Greenwich Village. Clement Moore, who finished first in his class at Columbia and later produced the first Hebrew lexicon in the US, was mindful of his literary reputation and never intended his Christmas confection to be heard beyond the walls of Chelsea House, as his English-born grandfather had named the manor.

With guests and family assembled, Moore uttered what would become an immortal couplet: ’Twas the night before Christmas, when all through the house / Not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse. The poem describes the Christmas Eve antics of St. Nicholas, the beloved fourth-century patron saint of children. The cult of St. Nicholas had died in Europe with the Protestant Reformation — except in the Netherlands, where, on December 5 of each year, the eve of his feast day, Dutch children would set out their shoes in hopes that Sinterklaas (sinter means saint, and Klaas is the Dutch short form of Nicholas) would judge them tenderly and leave them candy and not a lump of coal.

But in America, St. Nicholas was barely known outside the old Dutch community, and Moore, who was not Dutch, assimilated for his character a pastiche of European and American influences, including A History of New York by the fictitious author Diedrich Knickerbocker. The parody, which was published in 1809 by Moore’s friend Washington Irving 1821HON, chronicles the city’s little-known Dutch origins. Early in the story, Oloffe Van Kortlandt, a wealthy, real-life Dutch colonist, has a dream in which St. Nicholas descends from above the treetops in a flying wagon, lights a pipe whose swirling smoke takes the form of a spired city (which the dreamer takes as an omen to establish New Amsterdam), and rubs his finger beside his nose before mounting to the sky. The book was reprinted in 1821, the year before Moore wrote “A Visit.” Moore borrowed the pipe and the finger gesture (“And laying his finger aside of his nose / And giving a nod, up the chimney he rose”), and endowed his St. Nick with other traits that would come to define the American Santa Claus: a plump, jolly, cherry-nosed, white-bearded chimney spelunker whose toy-packed sleigh, drawn by team of reindeer, makes its yearly flight over the rooftops not on December 5 but on Christmas Eve.

As the story goes (and there are many stories), a Moore family friend, Harriet Butler of Troy, New York, heard Moore read the poem and asked to copy it down. A year later, at Christmastime, Butler’s friend Sarah Sackett submitted the unsigned poem to the Troy Sentinel, which published it anonymously. The poem, author unknown, spread to other papers, becoming an early-nineteenth-century viral sensation. It wasn’t until 1837 that poet and editor Charles Fenno Hoffman 1837HON published the twenty-eight rhyming couplets under Moore’s name in a collection called The New-York Book of Poetry. But Moore remained mum about his authorship and did not explicitly claim credit until 1844, when, after seeing the poem misattributed in the Washington National Intelligencer, he revealed himself as the author of “some lines, describing a visit from St. Nicholas, which I wrote many years ago ... not for publication, but to amuse my children.” That same year, he included “A Visit” in a book of his own poems.

And that would have been the end of any mystery of attribution, except for one problem: the family of Henry Livingston, a gentleman farmer from Poughkeepsie, insisted that it was Livingston, not Moore, who wrote the Christmas classic.

Livingston, a veteran of the American Revolution and a composer of light verse of the sort published in newspapers, died in 1828. There is no record of his ever having claimed authorship of “A Visit,” and no physical evidence linking him to the poem. Yet his progeny never stopped pressing his case. For more than 150 years their pleas went unheard. Then, in 1999, Mary Van Deusen, a Livingston descendant, enlisted the services of Don Foster, a Vassar English professor and literary sleuth. Foster’s specialty is crunching data from authors’ digitized writings to identify idiosyncratic patterns of syntax, vocabulary, and punctuation. It was Foster who pegged Joe Klein as the author of Primary Colors, and who had analyzed texts in the high-profile cases of JonBenét Ramsey and the Unabomber. Believing that idiosyncrasies of writing are as distinctive as fingerprints, Foster took on the Livingston case and published his findings in his 2000 book Author Unknown: On the Trail of Anonymous.

Apart from his speculations that Moore’s dourness and pedantry would have disqualified him from writing anything so sprightly, Foster unloads a sack of circumstantial evidence in favor of Livingston, whom he paints as a cheerful, playful, broadminded composer of children’s lyrics. Foster notes that the meter of most of Livingston’s poems, like that of “A Visit,” is anapestic — two unstressed syllables followed by a stressed one — while Moore is associated with only one other anapestic poem, “The Pig and the Rooster,” a scolding allegory about sloth and pride. Foster also keys in on the unusual use in “A Visit” of the word “all” as an adverb (“all through the house,” “all snug in their beds,” “dressed all in fur” and “all tarnished,”), which he finds consistent with Livingston’s work but not with Moore’s.

Then there is the question about the names of two reindeer, originally published as “Dunder and Blixem” (after the Dutch oath meaning “thunder and lightning”) but which became the German “Donder and Blitzen” in the four copies of the poem that Moore, late in life, wrote out and distributed as gifts. That Livingston was three-quarters Dutch and knew the language — and that Moore did not — was further proof for Foster that Livingston wrote the original, to say nothing of the very choice of St. Nicholas, an obscure figure who would hardly fall within Moore’s Anglo-Saxon Protestant bailiwick. To Foster, Moore was a thief and a liar.

Foster’s book caused no small stir among the country’s spirited clique of Santa Claus scholars. Seth Kaller, an appraiser of historical documents who in 1997 bought one of Moore’s handwritten copies of “A Visit” for $211,000, took on Foster’s claims point by point on his website, marshalling counterexamples and pointing out Foster’s “convenient” omissions of evidence favoring Moore. Another Santa savant, Scott Norsworthy, proprietor of the blog Melvilliana, launched an obsessively detailed and devastating rebuttal of Foster, furnishing images of contemporaneous nineteenth-century texts that undermine Foster’s claims about word usage. As for Moore’s exposure to Dutch tradition, or lack of it, historian Stephen Nissenbaum ’63GSAS, in his 1988 book The Battle for Christmas, notes Moore’s connection to John Pintard, civic leader and founder of the New-York Historical Society, who venerated St. Nicholas and in 1810 held New York’s first St. Nicholas Day celebration.

The Pintard link is crucial, according to Jared Goldstein ’89CC, ’97BUS, a professional tour guide who gives walking tours highlighting New York’s contributions to the birth of Santa Claus. “Moore was present at Pintard’s 1810 St. Nicholas Day dinner, and so was Washington Irving,” Goldstein says. “That evening, Pintard spoke the words ‘Santa Claus,’ which was possibly the first time the Anglicized form of Sinterklaas was spoken in America.”

Nissenbaum, in an essay called “There Arose Such a Clatter: Who Really Wrote ‘The Night Before Christmas’? (And Why Does It Matter?),” writes that Moore and his social circle “felt that they belonged to a patrician class whose authority was under siege,” and that their interest in St. Nicholas “was part of a larger, ultimately quite serious cultural enterprise: forging a pseudo-Dutch identity for New York, a placid ‘folk’ identity that could provide a cultural counterweight to the commercial bustle and democratic misrule of the early-nineteenth-century city.”

For his own part, Moore once stated that he got the idea of portraying St. Nicholas from “a portly, rubicund Dutchman living in the neighborhood,” sometimes identified as his gardener. But medievalist scholar and St. Nicholas enthusiast Charles W. Jones, in his 1954 essay “Knickerbocker Santa Claus,” published by the New-York Historical Society, proposed that the Dutchman who really influenced Moore was Gulian Verplanck 1801CC, 1835HON.

A Santa freak down to his breeches, Verplanck, who was elected to Congress in 1825, helped found the St. Nicholas Society and the St. Nicholas Club, and had known Moore at Columbia. In the pivotal year of 1822, Verplanck was, with Moore, one of six professors at the new General Theological Seminary. “At Christmas 1822, Verplanck and Moore were close indeed,” Jones writes. “If you think, as I do, that St. Nicholas is a little out of Moore’s natural channel, look to Gulian Verplanck.”

Moore lived to see his poem, treasured by millions as an enchanting evocation of the season, become the template for the character of Santa Claus. And when Moore, who was a Columbia trustee for forty-four years, died in 1863 after a short illness, the New York Herald hailed him as “one whose name will live long after him in the minds of the young through many generations.” Today, he is remembered at Columbia’s annual Yule Log festivities, which have long included a recitation of “A Visit from St. Nicholas.”

Moore is buried at the Trinity Church Cemetery and Mausoleum, between West 153rd and West 155th Streets between Broadway and Riverside Drive, where he shares repose with John James Audubon, John Jacob Astor, and Alfred Tennyson Dickens, a son of Charles Dickens. Each year, at the nearby Church of the Intercession, parishioners gather for a reading of “A Visit” and then walk across Broadway to visit Moore’s grave.

There are other Moore landmarks. On his Santa tours, Goldstein visits the Church of St. Luke in the Fields on Hudson Street (Moore was the first pastor); Moore’s townhouse (built in 1841) on West 22nd Street; and Clement Clarke Moore Park at West 22nd and Tenth Avenue, which had been part of Moore’s vast estate.

The park’s playground is an apt symbol, given Moore’s influence on the young. But one thing Goldstein has noticed on his tours is that Moore’s poem isn’t just for kids.

“Adults have it memorized,” he says. “When you think about it, ‘A Visit from St. Nicholas’ is probably the most famous poem ever written by an American.”