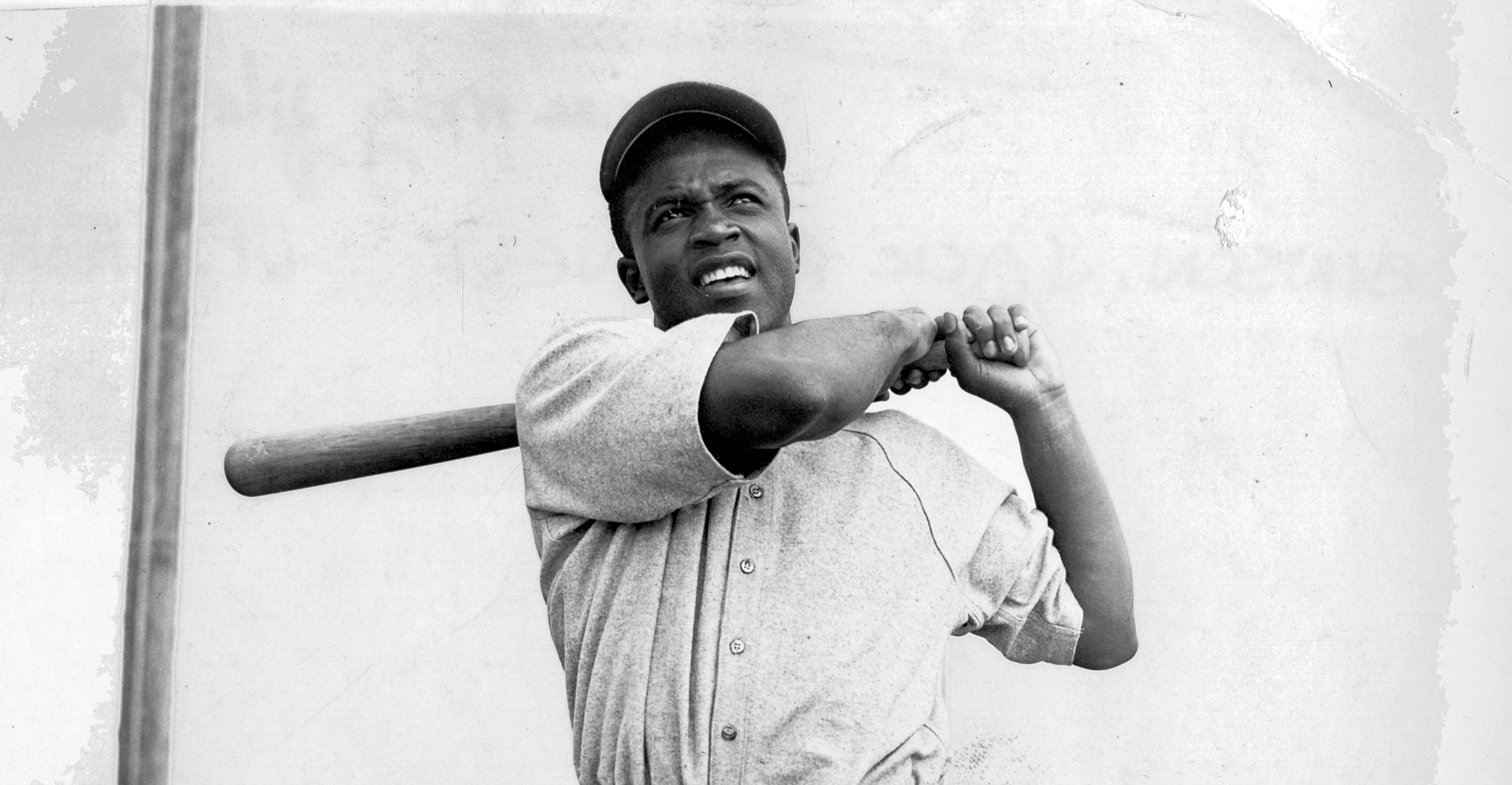

Numbers speak. They tell a story. Remember baseball cards? Kids could recite a player’s stats by heart. Those numbers added up to something — the sum of one’s skill and effort. Take Jackie Robinson, the Brooklyn Dodgers infielder who broke baseball’s color barrier in 1947: 125 runs scored his rookie season; a .342 batting average in ’49; six pennants; nineteen career steals of home plate.

Sharon Robinson ’76NRS knows her father’s numbers. But what if someone were to keep track of her professional stats — as a nurse midwife? Fifty births within her first six months of practice . . . a hundred within the first year . . . 250 after five years. Sharon has delivered some 750 babies — Hank Aaron territory. And that’s not counting the births she’s overseen as a teacher, first at the Columbia School of Nursing and later at Yale, Howard, and Georgetown.

There’s more. How about nine books published, 1,500 students who have received scholarships from the Jackie Robinson Foundation, and thirty-two million kids reached by Breaking Barriers: In Sports, In Life, the educational program that Sharon started in 1997? Those numbers tell many stories.

What if there were bubblegum cards for everyone?

Sharon Robinson is awfully approachable for a member of cultural royalty. She’s unpretentious, contemplative, quick to laugh. You can see her father in her face, can hear him in her voice, but after a minute you can almost forget that this is the daughter of an American folk hero.

When Sharon was born, in 1950, her father was one of the most famous, most important people in the country. As the first Black player in the majors in the modern era, Jackie Robinson had electrified baseball with his dynamic, aggressive style and ferocious will, and through his courage and dignity he had moved the nation forward. Polls rated him second in popularity only to Bing Crosby, and Life photographers showed up to take family portraits a decade before the Kennedys and the astronauts.

Being Jackie Robinson’s daughter came with blessings and challenges. “I learned very early on that I shared my dad with the world,” Sharon says. Her father was a passionate civil-rights activist who marched with Martin Luther King Jr., and he instilled in his family an ethos of service and a commitment — “an ongoing family mission,” says Sharon — to work for social change. “A life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives,” Jackie Robinson often said. The words are inscribed on his tombstone, and Sharon lives by them.

Sharon was six when her dad retired from baseball, after the 1956 season. To protect his family’s privacy, Jackie Robinson had moved the family from an integrated neighborhood on Long Island to a new house on six wooded acres in North Stamford, Connecticut. There was a lake on the property, which the kids — Jackie Jr., Sharon, and David — would skate on in winter. Sharon recalls her father, who couldn’t swim and was afraid of water, walking out on the frozen surface each year to test the thickness of the ice.

To her dad, she was “sweet, shy Sharon” — so sweet, he’d say, that she could sweeten his tea with her pinky. Her mother, Rachel, was beautiful, sophisticated, and accomplished. Sharon and her brothers were raised in the glow of excellence and fame, and inevitably that glow cast shadows. How could they ever measure up? Or establish their identities, or own their success? Even Sharon, the girl, the middle child, who’d never had baseball bats shoved into her little hands by strangers with cameras, became aware, as she got older, of the pressure to achieve.

She was an athlete in high school. She played basketball, softball, and volleyball, and loved to swim. In many ways it was a normal childhood: family dinners, games of Monopoly with Dad, afternoons watching soap operas with her maternal grandmother, who lived with the family. (The Doctors was their favorite.) Sometimes Sharon would sneak off with her grandma’s romance novels. Sharon had always figured she’d get married and have lots of kids, and maybe even write a romance novel of her own. But her mother, a psychiatric nurse who taught at Yale, was pushing her toward college and a career.

Meanwhile, her mother and grandmother pampered the boys: rebellious, sensitive Jackie Jr. and adventurous, funny David. And Dad was at the center of everything.

"My mother is very pro-male — whether it’s the boys or my father, they’re exalted,” Sharon says. “Part of it is cultural in the Black community, because we see the males as more targeted; they’re the bigger threat to the status quo. We want them to be safe. We think we’re building their self-esteem, but actually, it forces the women to be ultra-strong and sort of weakens the men.” Sharon laughs. “We should push them out of the nest earlier. That’s typically what Black families do with the girls: they push them out. We’re not going to pamper you; you’re going to have to take care of your family, your church, and your community.”

Sharon had known since she was a girl that she wanted to work in a hospital someday (maybe it was all those hours watching The Doctors), and in 1968 she entered Howard University to study nursing. Also that year, against her parents’ wishes, she married a young man who, unbeknownst to her parents or anyone else, had been abusing her physically and emotionally for two years, shattering her already fragile self-esteem. They were married for a year before Sharon found the strength to leave. Then, in 1971, her brother Jackie, who had survived a tour in Vietnam and conquered an addiction to heroin, died in a car crash at twenty-four.

By the time of the 1972 World Series in Cincinnati, where her father was to be honored on the twenty-fifth anniversary of his breaking the color barrier, Sharon was at a low point. Her second marriage was collapsing, she was mourning her brother, and she was still coping with the trauma from her first marriage.

Yet she cherished that moment in Cincinnati. The family stood strong together, though her father, white-haired and blind in one eye, appeared older than his fifty-three years. His diabetes had advanced, and his heart was failing. Nine days after the tribute, Jackie Robinson died.

The funeral was held in New York at Riverside Church. Jesse Jackson gave the eulogy. No grave can hold this body down, he said. It belongs to the ages.

After her brother’s death, Sharon had watched her mother crumble and then put herself back together. Rachel Robinson, like her husband, was a fighter, and Sharon took her cues from her mother’s resilience.

She was grateful, too, that toward the end of her father’s life, she’d had a chance to spend some time with him talking about her future. Sharon was interested in women’s health and brought up the idea of going to medical school for obstetrics and gynecology. Her dad was delighted: it didn’t matter to him if she went or not; he was simply pleased that she had the faith in herself to consider it.

As it turned out, Sharon chose another path. At Howard she’d learned about midwifery, and the more she thought about it, the more she realized she didn’t want to do C-sections. She wanted to be part of the entire birthing process. She wanted to be a midwife.

Columbia’s School of Nursing had a graduate nurse-midwifery program. Established in 1955, it was the first of its kind in the nation. For Sharon, Columbia was ideal: a pioneering school in an urban setting, where she could work with a diverse population. She got in and got started.

“It was a very exciting time, because women’s health care was changing,” Sharon says. “Women were getting basic rights around contraception and abortion and childbirth itself: having more choice in how they delivered, having a voice in their care, and bringing the family into the birth experience. That was all part of my era.”

After graduating from Columbia, she got an internship at LA County Hospital. “It was one of the best internships in the country, with a massive amount of births, and I got a lot of experience in six months. I had to deliver in all sorts of crazy circumstances. Sometimes the women delivered in the hallway.” She next joined a small home-birthing practice in West LA: when her beeper went off she’d ride her bike from her home in Venice to the moms-to-be in Santa Monica. “Midwives in this country started off in Kentucky and rode horses,” says Sharon, who had a horse as a girl. “Think of it as the contemporary Kentucky midwife for the beach folks.”

Her next stop was San Francisco General Hospital, where she dealt with pregnant teens. “That was my subspecialty: adolescent health and working on self-esteem, since self-esteem had been such a big issue for me. I used my time with the teenager to help her build confidence and let her know that part of being a good parent is being sure of yourself.”

A good midwifery experience means you have a bond with the expectant mother from labor to delivery, Sharon says. She spent many hours in dimly lit birthing rooms, listening. And then came the birth. “That’s what I miss the most — the touch, the feeling of a baby, of a new life coming out, and you’re there holding it and passing it to the mother. It’s incredible to see.”

1978 was another tumultuous year. Sharon got engaged, then pregnant, and then left her fiancé and moved back east, where her son Jesse was born. She stayed at home with Jesse for a year, and then, in the fall of 1979, she returned to Columbia to teach at the School of Nursing.

Jesse was everything to Sharon. He was not an easy child to raise. He had dyslexia and ADHD, speech and hearing problems — “a whole host of things that required intervention,” Sharon says. “I found it challenging to handle all that as a single parent.” After three years at Columbia, Sharon needed the structure of a nine-to-five, so she took a job leading PUSH for Excellence, Jesse Jackson’s educational nonprofit for high school students.

In 1987, while at PUSH, Sharon spoke to Ebony magazine for an article about whether having a famous name helps or hurts. In it, Sharon disclosed that she had gotten engaged in high school because she wanted to change her name. “I didn’t realize it at that point,” she said, “but I wanted to be anonymous.” She kept her married name at Howard to avoid preferential treatment; it was imperative that she make it on her own. And having seen what Jackie Jr. had gone through — the constant, impossible comparisons — she had declined to name her son Jack. But she soon reclaimed her Robinson name. As she told Ebony: “Once you integrate it into your total being, it is a major asset, especially in my case, because my father had a great deal of respect from all kinds of people.” The Ebony writer told her she ought to write a book about her life.

And so Sharon began carrying around a pad, jotting down thoughts. “I wasn’t sure it would ever be a book; I was just writing and doing research on what it means to be abused by your spouse,” she says. “Then I figured if I could write that part, I could write anything.”

Her memoir, Stealing Home, came out in 1996 from Harper-Collins. In it, she discussed her childhood, her family life, the difficulties that came with integrating her all-white school and neighborhood, her marriages, her father’s politics, and her parents’ partnership. She has since published two young-adult novels and seven children’s books.

She plans to write at least one more.

In 1997, the golden jubilee of Jackie Robinson’s history-shaping appearance on a ball field, Sharon attended the ceremony at a Mets-Dodgers game at Shea Stadium. Her son threw out the first ball, and her mother and President Clinton gave speeches. That same year, Sharon joined Major League Baseball as vice president of educational programming, teaming up with the publisher Scholastic to create a program for character development in children. After twenty years in nursing, Sharon was ready for her next chapter. Her program, Breaking Barriers: In Sports, In Life, was born.

“We introduce kids to nine values that I associate with my dad’s success on and off the field: courage, determination, teamwork, persistence, integrity, citizenship, justice, commitment, and excellence,” Sharon says. “We use those values to provide strategies to help kids overcome obstacles in their lives.” The curriculum includes an essay contest, for which two grand-prize winners are honored at the All-Star Game and the World Series.

Sharon is also vice chair of the Jackie Robinson Foundation (JRF), a scholarship program for low-income students of color that her mother founded in 1973. Martin Edelman ’66LAW is cofounder and secretary. The chair is Gregg Gonsalves ’89SEAS, who attended Columbia as a Jackie Robinson Scholar.

“The JRF is my mom’s baby,” Sharon says. “She is very powerful and self-directed, and very clear in what she wants to accomplish. She doesn’t take on something that she’s not going to push to be successful.”

This spring, the JRF broke ground on the Jackie Robinson Museum, scheduled to open in SoHo in 2019. It won’t be just artifacts and baseball. “There’s no civil-rights museum in New York City,” Sharon says. “We feel this museum will fill that gap, and we’re excited to get it done in my mother’s lifetime.”

Though Sharon is dedicated to this work, she’s also looking ahead. “My mother is ninety-four, and I’m very much supporting her during this phase of her life,” she says. “But I know it’s important I figure out my next phase.”

The essays for the Breaking Barriers contest are about facing adversity, and many of them center on illness — a topic Sharon knows well. She has lupus (an autoimmune inflammatory disease) and high blood pressure. In 2008 she had a double bypass.

Around that time, Jesse, then twenty-nine, got sick and fell into a coma for two weeks. He was diagnosed with adult-onset type 1 diabetes, like his grandfather. “It runs in my father’s family in the males,” says Sharon. “They get a very virulent form of diabetes and heart disease. It had skipped a generation with my brother, and I knew my son was going to get it. I just knew.”

Though Jesse survived the coma, his symptoms worsened. In 2013, he had a heart attack, which proved fatal. He was thirty-four.

On April 15, 2017, Sharon arrived at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles, ten miles from Pasadena, where Jackie Robinson grew up. Seventy years had passed since that immortal day at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn when Jack Roosevelt Robinson in his white Dodgers jersey strode pigeon-toed across the grass to the infield dirt.

Guests and dignitaries gathered in the left-field plaza: Sharon’s mom, Rachel; Sharon’s brother David, who lives in Tanzania, where he runs a coffee cooperative; the extended Robinson family; Jackie’s teammates Sandy Koufax, Don Newcombe, and Tommy Lasorda; Dave Roberts, the team’s first Black manager, now in his second year; Dodgers part-owner Magic Johnson; and Dodgers CEO Stan Kasten ’76LAW. Nearby, blue curtains veiled a statue — the first ever for Dodger Stadium.

On the count of three the curtains fell, revealing Jackie Robinson, in bronze, sliding toward the plate, his right fist extended as he completes baseball’s most daring play: stealing home.

Sharon was grateful to have shared the moment with her mother. These occasions are far more than celebrations.

“Anniversaries let us focus not only on the past, but on where we are now,” Sharon says. “They help us see where we still need to work hard to reverse the backsliding, and to move things forward. They are moments of reflection, and not just for baseball.”

Sharon Robinson loves the water. She divides her time between New York and Delray Beach, Florida. The beach in Delray is beautiful; the water, healing.

“I’ve been trying to figure out who I am since my son died,” Sharon says, matter-of-factly. Fortitude and grace suffuse her; there are no stats for that.

Jesse had two children. Jessica is six, and Luke is eleven. They live in Massachusetts, and Sharon hopes to see more of them.

She’s been thinking more about the next phase of her life.

“Slowly,” she says, “I’m beginning to visualize what that will look like.”

Her favorite time to walk the beach is sunrise, when the fishermen are setting out in their boats. A golden rim appears on the watery horizon — a crown, lifting as if for the first time — and the world feels calm.

“I have one more book I’m going to do for kids,” Sharon says, peering into the future. She laughs, almost bashfully. “Then maybe I’ll get to write some love stories.”