I. Tanya Domi remembers a garden, a pot of coffee, Madeleine’s cigarettes, and a sunny spring day on the west side of Sarajevo.

It was May 2001, and Domi ’07GSAS, who from 1996 to 2000 worked in Bosnia for the U.S. State Department as a human-rights and media-rights officer and as spokesperson for the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) in Bosnia and Herzegovina, had returned to Sarajevo to follow up on her academic research. Her first order of business was to visit her friend Madeleine Rees, the British-born head of the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in Bosnia.

Domi’s concern was sex trafficking. She had learned of the horror during her years in postwar Bosnia with OSCE. The sex trade in Bosnia was an open secret among UN contractors, a situation that Domi found especially grievous, given that during the Bosnian War, from 1992 to 1995, tens of thousands of women had been raped as a matter of policy. Many died, by injuries or suicide. Others were sold into slavery. It was unthinkable, then, that UN peacekeepers in Bosnia, there to help bring order to a country that had seen rape camps and mass slaughter, could be involved in human trafficking.

Prostitution is illegal in Bosnia, but international personnel had full diplomatic immunity, and, in any case, the plight of women was not a burning issue for the international forces there. Domi had been in rooms with men like U.S. ambassador to the UN Richard Holbrooke, NATO commander Wesley Clark, and U.S. Army Europe commander Eric Shinseki, where, as Domi later said, the issue of sex trafficking never came up. “Never. Women were just not a priority.”

In the garden, Rees leaned back in her chair, smoke unwinding from her fingers, a copper coffee cup in her hand, and told Domi about a UN peacekeeper named Kathryn Bolkovac.

Bolkovac was an ex-cop from Nebraska and a divorced mother of three. In 1999, looking for a change in her life, she took a job with DynCorp, the government-services company that the State Department had hired to recruit American peacekeepers for the mission in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The contract paid $100,000 for six months. Bolkovac became an investigator in the UN Gender Affairs Office, and uncovered an appalling scandal: UN monitors, including some DynCorp employees, were not only patronizing the hundreds of brothels that had sprung up around the peacekeeping presence in Bosnia, but were buying, selling, and transporting women and girls, most of whom came from the former Soviet Union. When Bolkovac reported the problem to her superiors in the UN International Police Task Force (IPTF), she was told to back off — no joke in a part of the world where accidents could happen. Military commanders removed her case files. But Bolkovac kept pressing. In 2000, the UN relieved Bolkovac of her duties, after which DynCorp fired her for allegedly falsifying her time sheets.

Domi had heard some outrageous things during her years in Bosnia, but she was still shocked by Rees’s account.

“Are you going to the press with this?” Domi said. “Are you ready to go public?”

“Yes,” Rees told her. “I’m ready.”

The women agreed that the story should be broken in a Bosnian paper, out of regard for a population whose trust had been so profoundly violated. Domi had worked in media development in Bosnia and had even written articles for Oslobodjenje (Liberation), Bosnia’s oldest daily newspaper.

“How would you feel about my doing this through Oslobodjenje?” Domi said.

Rees didn’t have to think. “Tanya,” she said, “you’ve got to get this out.”

The timing was crucial. In just a few weeks, on June 14, Jacques Paul Klein, head of the UN mission in Bosnia and Herzegovina, was scheduled to address the UN Security Council. Months earlier, Rees had confronted Klein about the mistreatment of Bolkovac, and Klein responded by going to UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan to get Rees fired. But Rees had two key allies — Mary Robinson, the UN high commissioner for human rights, and Angela King, Annan’s special adviser on gender issues — and Klein’s maneuver failed. “Madeleine outflanked him,” Domi later recalled.

That seemed to be happening again, in the garden in west Sarajevo. Rees handed Domi a folder of documents, and Domi drove back to her apartment near the Sarajevo Brewery and phoned the editor of Oslobodjenje.

II. Sex trafficking?

Like most people in North America, Larysa Kondracki had never heard of it. But in 2003, Kondracki ’01GS, then a graduate film student at Columbia, was visiting her parents in Toronto when the topic came up. The Kondrackis belonged to that city’s large Ukrainian-Canadian community, and were aware that many of the victims of sex slavery in Europe came from places like Ukraine and Moldova, poor countries hit hard by the economic turmoil that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union.

A week later, Kondracki, who was searching for an idea for her thesis film, received a package from her mother: a recent book by the Canadian journalist Victor Malarek called The Natashas: Inside the New Global Sex Trade. Kondracki was horrified and fascinated by what she read. She came to a section on the UN, and it was there, in a brief passage, that she first saw the name Kathryn Bolkovac.

The freewheeling early 2000s were good years to be in film school. “It was the height of the million-dollar short, where anything seemed doable,” Kondracki says. “It was also the time of Boys Don’t Cry and High Art and Monster, all these amazing, low-budget first features. And a lot of Columbia professors were saying, ‘Hey, maybe you can do your thesis as a feature film.’”

Kondracki knew she wanted to examine sex trafficking. A producer friend, Christina Piovesan, told her that she needed to find a way in. “So I went back and reread The Natashas, because nobody can take a two-hour movie of just sex trafficking,” Kondracki says. “I found that bit about Kathy again, and, when I googled it, I saw that it was all over the news — or at least the European news.”

Kondracki took the idea to a screenwriter in the graduate program, Eilis Kirwan ’04SOA, who agreed to collaborate with her on the script. Kirwan lived in Ireland, a convenient base from which the two women could make their research trips. In February 2004, Kondracki and Kirwan visited Kathy Bolkovac at her home in the Netherlands. That summer, the writers set out on a six-month rail trip. They began in Vienna, where they spoke with OSCE officials, then journeyed to Poland, Romania, Ukraine, Georgia, Bulgaria, Bosnia, and Kosovo. They visited underground shelters for trafficking victims, literal holes in the ground that housed a half dozen frightened girls, run by women who, Kondracki says, “were risking their lives.”

Over the next five years, the screenplay of The Whistleblower took shape. In 2009, the project, funded with Canadian and German money, attracted two big stars for the lead roles: British actress Rachel Weisz would play Bolkovac, and another Briton, Vanessa Redgrave, would play Madeleine Rees.

The movie was green-lighted. Kondracki began shooting in Romania in late October 2009. That same week in New York, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon gave his annual United Nations Day message. “On this UN Day,” he said, “let us resolve to redouble our efforts on behalf of the vulnerable, the powerless, the defenseless.”

III. Tanya Domi’s article broke in Oslobodjenje in early June 2001. An English-language version also appeared on the website of the Institute for War & Peace Reporting. The piece was stark and direct. “Bolkovac alleged that extensive trafficking of women into prostitution had been carried out by UN personnel, NATO troops, and other international officials in Bosnia, along with the local police,” Domi wrote. “Bolkovac was diagnosed as ‘stressed and burned out’ by the IPTF deputy commissioner Mike Stiers, and her contract with the UN was subsequently terminated by DynCorp, the U.S. State Department’s personnel subcontractor for the UN Mission.”

After filing her report with Oslobodjenje, Domi approached her friend Aida Cerkez, the bureau chief for the Associated Press in Bosnia, and helped Cerkez prepare a story for the wire.

The bid to put Jacques Paul Klein on the defensive succeeded. By the time Klein stood before the Security Council to talk about the UN effort in Bosnia, all the member states had the documents, and reporters were ready with questions.

But Klein had come prepared. He announced that the Bolkovac matter had been brought to his attention, that the UN was not involved in human trafficking, and that there was no cover-up, but that, in response to Bolkovac’s complaints, he was implementing a measure called STOP — the Special Trafficking Operations Program — which would include a series of raids on brothels.

“He knew he had to cover his ass,” says Domi. “The raids were done as a reaction, and it was a good show. But the real work that Bolkovac had done in confirming the identities of UN personnel and Bosnian officials involved in sex trafficking was never presented in a court of law.”

Still, the reporters seemed satisfied with Klein’s response, and so did the members of the Security Council.

IV. “The term human trafficking can be problematic,” says Siddharth Kara ’01BUS, the author of Sex Trafficking: Inside the Business of Modern Slavery and a fellow of Human Trafficking at Harvard’s Kennedy School. “‘Trafficking’ tries to encapsulate everything — acquisition, movement, and exploitation — but the nature of the term focuses on the movement, and, as a result, we’ve become fixated on movement. Do we stop movement? Do we make movement the crime?

“But the movement is almost always incidental to the exploitation. We used to refer to the acquiring and movement of people for the purpose of selling them into servitude or exploiting them as slaves as ‘slave trading,’ and it was very clear exactly what was going on.”

In the summer of 1995, Kara, then a Duke undergrad, spent eight weeks as a volunteer in a refugee camp near the town of Novo Mesto, Slovenia. The camp was filled with Bosnian Muslims who had been routed from their homes. Kara lived as the refugees did, on “stale bread, oily soup, and rotting brown salad.” He lost 18 pounds. His main occupation was listening to survivors’ stories of death and despair. A particular atrocity bore into his conscience: Serbian soldiers, he was told, had raped countless Bosnian women and trafficked them to brothels across Europe.

Five years later, Kara, still haunted by the stories, began poking around in libraries to see what research and analysis was being done on sex slavery. He didn’t find much. Then, in 2000, while getting his MBA at Columbia, Kara decided that his own advantages and abilities required him to dig deeper.

“I had a diverse background in finance and economics and literature, and eventually law as well, and I thought, Let me take a plunge and see what I come up with,” Kara says. “I knew that in essence these were economic crimes.”

Kara’s self-funded odyssey took him around the world and under it — down into the brothels, sex clubs, and all-night massage parlors of India, Nepal, Burma, Thailand, Vietnam, Italy, Moldova, Albania, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Mexico, and the United States. With hired guides and translators, he traveled to big cities and remote villages to get a grasp of economic conditions; made his way to border towns to observe the mechanisms of transport; and met with former and current slaves, the majority of whom were too terrified, distrustful, and traumatized to speak. “Most victims I interviewed were under the age of 25,” Kara reported in his book, “and most suffered debilitating physical injuries, malnutrition, psychological traumas, post-traumatic stress disorder, and infection by a scourge of sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV/AIDS.” Dozens of Kara’s subjects were minors.

Kara estimates that there are between 22 and 30 million slaves worldwide, forced into everything from prostitution to construction. By Kara’s calculation, the sex-slavery market generated about $38 billion in 2010, making it one of the world’s fastest-growing criminal industries. He credits the global marketplace for driving down prices to the point of stimulating new demand.

“If you take the fundamental premise that slavery has always been about maximizing profit by minimizing or eliminating the cost of labor, the nature of globalization puts that formula on steroids,” Kara says. “It’s not just acquiring people from one continent, spending weeks to cross seas, and then putting them to work in agricultural servitude, which you can monetize once or twice a year depending on the crop; you can now acquire poor, desperate, vulnerable individuals from almost anywhere for a very small amount, transport them to almost anywhere in the world within a day or two or three for a relatively small cost, and then, in the case of commercial sex, monetize them several times a day.”

In The Whistleblower, a Ukrainian teenager, Raya, is sold into slavery by her uncle, who had promised her and her friend jobs in a hotel. Kondracki describes a crucial step in the trafficking process that she didn’t depict onscreen: “The traffickers hold these girls and repeatedly rape them and beat them, burn them in discreet places, behind the ear and on the bottom of the foot, and break them down, to the point where they can sell them. Then they give them this weapon of hope, which is, ‘You can rebuy your life.’ If you look at how psychologically advanced the crime is, it’s quite brilliant, in a way.”

What Kondracki does show, through the eyes of Weisz’s Bolkovac, is awful enough. The Polaroids that Bolkovac finds tacked to a wall in a raided bar tell the story: young, listless girls being groped by partying peacekeepers wearing UN T-shirts. What might look at a glance like vulgar frat-house hijinks becomes, as we absorb the context, a ghoulish tableau of human misery. Then, in the searching beam of Bolkovac’s flashlight, we see the slaves’ dungeon-like living quarters, suffused with the gunmetal blues and grays of contemporary noir: filthy mattresses, strewn condoms, syringes, a waste-filled bowl, and, most startlingly, metal chains and cages.

The Whistleblower’s sharp, straightforward script evokes a 1970s conspiracy thriller (Kondracki’s favorite kind of movie growing up), and the movie’s dark, stylized look exposes a vivid moral ugliness, rendered in the gaudy hues of smeared makeup, bruises, and dried blood. But the movie might well be remembered for its one explicitly brutal scene. In it, Raya, whom the police had handed over to Bolkovac after finding her dazed and beaten, is recaptured by her traffickers, and now they will make an example of her. The other girls are forced to watch, their screaming faces wide with terror as Raya, bent over a table, receives her punishment. None of them will talk to the police anytime soon.

V. The Whistleblower opened in New York on August 5, 2011. A New York Times review stated that the movie “tells a story so repellent that it is almost beyond belief.” In the months before the release, The Whistleblower’s distributor, Samuel Goldwyn Films, had proposed screening the movie for UN officials. The officials weren’t enthusiastic. The UN correspondents wanted to see it, though, and in July, Goldwyn Films gave them a screening at UN Headquarters in New York, followed by a press conference with Kondracki and Kirwan. Soon afterward, a private DVD screening was held for members of the UN media division.

But there was still no response from the top. Kondracki wanted a major screening for the entire UN staff, including Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, with a discussion to follow. Again, The Whistleblower team urged the UN to embrace the movie and show a willingness to confront its mistakes. The UN remained noncommittal.

Behind the scenes, however, The Whistleblower was being intensely debated. On July 5, assistant secretary-general for human rights Ivan Simonovic circulated an internal memo, which was leaked to Kondracki. It described a meeting among Ban’s senior advisers on how to handle the imminent PR challenge of The Whistleblower. Some voices called for a positive, proactive approach, with a public screening and dialogue. Others argued for ignoring the movie and making statements only if asked.

The memo stunned Kondracki; evidently, high-ranking UN officials had already seen The Whistleblower. Had the secretary-general seen it, too? How serious was this talk of a screening and discussion? Kondracki hadn’t heard about it, and neither had anyone at Goldwyn. What was going on?

Kondracki decided to find out: She sat down and typed a letter to Secretary-General Ban.

I have been made aware that UN leaders are split as to how to deal with this film, Kondracki wrote. I have heard that the UN is opting for a “damage control” mode. Sir, I strongly wish to impart to you how very wrong a decision that is. I believe in the United Nations. I believe in the values of such an organization, but I lose faith, not only when I hear of involvement in sex-trafficking, but when I hear that you may not want to use this opportunity to right those wrongs.

And then:

Please know that I was very careful to ensure that the film was not a sensationalized account of the story, but rather depicted very well-documented facts. To be completely honest, the film tones down the extent of the crimes being perpetrated. Crimes that were being committed by the very people who were meant to protect the innocent. I believe there is now a chance for the United Nations to own up to these events, learn from history, and begin to tackle how to make changes in future missions.

Kondracki put the letter into an envelope and sent it to the head of the UN correspondents, who personally delivered it to the office of the secretary-general. Included in the package was a DVD of The Whistleblower.

VI. In the summer of 2003, President George W. Bush, in a speech before the UN General Assembly, called the issue of trafficking and human slavery “the biggest human-rights violation of our time.” That same year, Congress passed the PROTECT Act of 2003, which made it illegal “to recruit, entice, obtain, provide, move, or harbor a person or to benefit from such activities knowing that the person will be caused to engage in commercial sex acts where the person is under 18 or where force, fraud, or coercion exists,” according to the U.S. Department of Justice. Three years earlier, President Bill Clinton had signed the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act, the first comprehensive federal law in the United States to deal with modern slavery.

At that time, Faith Huckel ’04SW was a social worker in Philadelphia. Huckel had seen a lot — women who were coming out of incarceration, who were HIV-positive, who had suffered domestic violence. But it wasn’t until she got to New York in 2003 to attend Columbia that she heard about sex trafficking. “To learn that this was happening in our own backyards was absolutely astonishing,” she says. “I became a little obsessed.”

One night in 2004, Huckel and two lawyer friends were sitting around a kitchen table, talking about the one thing they would do to change the world if they could. They all agreed that it would be to help the victims of sex slavery.

“So I told them about some of the research I’d been doing over the year, and mentioned that one of the biggest needs in the city is safe housing,” Huckel says. “Most women who have been sex-trafficked are placed in domestic-violence shelters or homeless shelters. We concluded that we wanted to start New York’s first long-term safe house for this population. It was important that the program be culturally and linguistically tailored to the survivors’ needs, and that they could stay for as long as their recovery was going to take.”

In October 2007, Huckel threw a fundraiser with a small group of friends, supporters, and volunteers. They raised $17,000. That got them started. By the following September, they had raised enough money for Huckel to work full-time. A few months later, the nonprofit, called Restore NYC, began cultivating a relationship with the Queens criminal court.

“If you are looking for trafficking survivors, you should go to the courts and see who’s being arrested on prostitution charges,” says Huckel. “Most of our clients come through Queens criminal court. Initially, they are seen as criminals. They’re seen as the problem. The city is arresting the wrong people. In our annual report, there’s a breakdown of trafficking arrests versus prostitution arrests, and the numbers are absolutely staggering. In 2010, there were 344 prostitution arrests in Queens and zero arrests for trafficking.”

Meanwhile, Huckel had to find a building owner willing to rent space to Restore NYC. “It came down to meeting the owner and saying, ‘This is what we do; it’s a smaller facility, we’re piloting this program for a year, and we are going to be taking on six clients.’”

Eventually, Huckel found a place in Queens. The facility opened in 2010 and filled up immediately. The women, who had been trafficked from China, Korea, and Mexico, were nabbed in brothel raids in Flushing or Corona and handed over to a criminal-justice system that really didn’t know what to do with them.

Today, in the Restore NYC house, the women busy themselves with activities — knitting, sewing, yoga, ESL classes, drawing. They are assigned household chores and are required to take a 12-week job-training course.

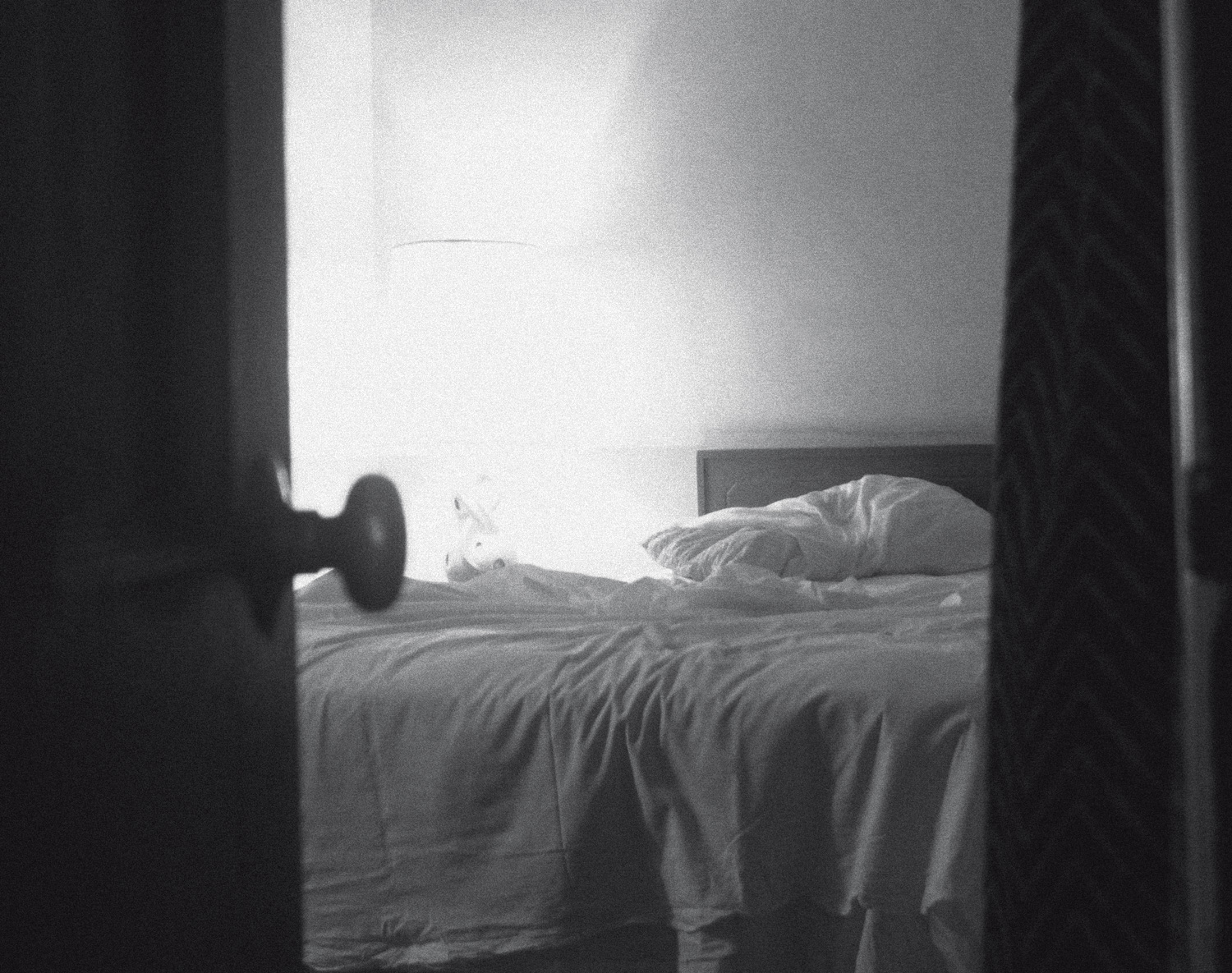

“When the clients come in, we see a huge distrust of everything and everyone, and rightly so,” Huckel says. “These are cases where girls were trafficked at 16, worked six years in New York in a room, were raped 20 or 30 times a day, were forced to have multiple abortions, had sexually transmitted diseases and complications, had probably attempted suicide. The list goes on. They’re shy, timid, quiet. There’s obviously a lot of PTSD, which presents itself as sort of a vacancy in their eyes. There’s no life.

“We tell all our coordinators and volunteers that the safe house is a home to these women. Don’t bring up their trafficking stories. Don’t pry, don’t ask questions; just support them and help them with the basic things that they need. Do they have the food they like and can cook? Do they have enough clothes? Are they comfortable in their rooms? Think of it as if you were an RA in a dorm; don’t dig deeper than that.

“Just giving the women the space to work stuff out has been unbelievably helpful,” Huckel says. “They can come home and shut their door and have privacy. They don’t have to worry about paying for food or rent. They can simply heal. In giving them space, supporting them, showing them a sense of love, you start to see the walls come down. It just takes time.”

Over the past decade, the number of U.S. programs for international and domestic sex-trafficking survivors has grown. Carol Smolenski ’92GSAS, the cofounder and executive director of the U.S. chapter of the international organization ECPAT (End Child Prostitution and Trafficking), has been focusing on changing state laws so that underage victims who through force, coercion, or manipulation of power have ended up in the sex trade are not arrested for prostitution.

“Many of these kids are sexually abused their whole lives, told by their parents to just get out of here, and end up on the street, leaving them vulnerable to a pimp who says, ‘Baby, you’re the greatest. I love you,’” Smolenski says. “The stories about the pimps are always the same. ‘Yeah, he told me I was beautiful.’ The pimps lure a 12-, 13-year-old girl and send her out on the street, and what does our system offer? We arrest her and tell her that she’s a bad kid who needs to be punished and reformed. A kid who’s been abused her whole life. And that’s the paradigm that has to change — we have to put protections in place for these kids, not arrest them.”

In 2008, the New York State Assembly passed the Safe Harbor for Exploited Children Act, which provides protections and services for exploited children as an alternative to incarceration. ECPAT-USA is working on getting similar legislation passed in New Jersey. In 2011, Minnesota and Vermont passed safe-harbor laws.

“It’s been a good year,” Smolenski says.

VII. 11 August 2011

Dear Ms. Kondracki,

I write to thank you most sincerely for your letter of 1 August and for sending me a copy of the film for my personal viewing.

Last week, I saw the film, along with our senior advisers. I was pained by what I saw. I was also saddened by the involvement of the international community, particularly the United Nations, in the abuses connected with the trafficking of women and their use as sex slaves, as highlighted in the movie.

The letter from Secretary-General Ban to the director of The Whistleblower went on to list the measures taken by the Security Council on the issue, such as appointing a special representative of the secretary-general on sexual violence in conflict, stricter standards for recruiting personnel, the addition of Conduct and Discipline Teams to peacekeeping operations, and due protections for “those who blow the whistle.” Ban went on:

But, I recognize, rules and measures alone are insufficient. The culture must change. I am determined to lead by example.

I welcome your suggestion that The Whistleblower be screened especially for United Nations staff. I propose to go further. I have asked that a special screening be arranged at United Nations Headquarters not only for staff but also for Member States, with full support of the President of the General Assembly. As suggested by you, after the screening we shall have a panel discussion as the starting point for a frank and honest discussion of the issues the film raises. I hope you will be able to join us in this engagement.

I want to assure you that we shall embrace the challenge your film places before the United Nations. The vulnerable women whose condition your film showcases will not be forgotten. Thank you for raising this issue with such passion.

The screening was scheduled for mid-October. Kondracki and Kirwan planned to attend.

VIII. In her fourth-floor office in Low Library, Tanya Domi, senior public-affairs officer at Columbia, is enjoying a moment of satisfaction over the news from Turtle Bay.

“That the secretary-general invited Larysa to screen the film at UN Headquarters represents a seismic change in attitudes,” Domi says. “After 10 years, this is really an about-face.”

But Domi cautions that it doesn’t fix everything: Neither DynCorp nor the UN has apologized to Bolkovac.

“The American people should be disgusted,” says Domi, who served in the U.S. Army from 1974 to 1990. “Disgusted that somebody went over there, did her job, uncovered incredibly heinous crimes, and was fired for it. Fortunately, Kathy came out of this intact. She did a brave thing, and I really believe that that comes out of being an American who knows the difference between right and wrong, and standing up and saying, ‘This is not okay.’ Now peacekeepers are held to an accountability that didn’t exist before. We have Kathy to thank for that.”

Ten years ago, Domi had expected that the story of Bolkovac would shake the U.S. media. That never happened.

“Colum Lynch of the Washington Post wrote a couple of stories, and there were a couple in the New York Times, but there was no ongoing coverage about Kathy, about DynCorp’s retaliation, about the fact that in 2003 a British labor tribunal unanimously found in Kathy’s favor. Despite all our best efforts in 2001, The Whistleblower has accomplished what the news media and law enforcement were unable to achieve.”

Domi pauses. On her desk is a photo of row upon row of slender coffins wrapped in bright-green cloth, containing victims of the Srebrenica Massacre of July 1995, in which 8000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys were murdered. On her shelves, among her books, is a Bosnian hand-hammered copper coffee set.

“I’m grateful to Larysa and her colleagues for making this film,” Domi says. “Kathy Bolkovac and Madeleine Rees are the real heroes here. I’m grateful that I got the opportunity to break this story, but as I’ve said to everybody: This is not going to be the end of this.”