Yes, the tribute to fifty years of James Bond movies at this year’s Oscars ceremony was memorable. A soignée Halle Berry, who’d starred in Die Another Day, introduced an explosive, rapid-fire action montage: the volcano assault in You Only Live Twice, the bobsled battle from On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, the minijet escape in Octopussy (you get the idea), after which seventy-six-year-old Shirley Bassey sang “Goldfinger” to a standing ovation.

But no one mentioned Bond creator Ian Fleming. Or Bond producer Albert R. Broccoli. Or Sean Connery, let alone George Lazenby. And it’s doubtful that anyone had even heard of Ernest L. Cuneo ’27CC, the man who sketched out what would have been the very first James Bond film.

Cuneo, a graduate of St. John’s School of Law, started out as a reporter for the New York Daily News and later became president of the North American Newspaper Alliance (NANA). Described by author Neal Gabler as a “born fixer,” he left the newspaper business to serve as law secretary for then congressman and future New York City mayor Fiorello La Guardia (Cuneo’s 1955 memoir Life with Fiorello inspired the 1960 Tony-winning musical Fiorello!), and later became associate counsel for the Democratic National Committee and President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s liaison to gossip reporter Walter Winchell, often writing many of Winchell’s items himself.

Cuneo was a close friend of Fleming’s. The pair met during World War II when Fleming was in British Naval Intelligence and Cuneo was working under Major General William “Wild Bill” Donovan 1905CC, 1908LAW at the Office of Strategic Services. After the war, Fleming saw Cuneo frequently in the States; he drew on their trip to Las Vegas for his fourth Bond novel, Diamonds Are Forever, even naming a cab driver “Ernie Cureo.”

“Ian Fleming was the warmest kind of friend, a man of ready laughter, and a great companion (everything James Bond is not!),” Cuneo wrote in the introduction to Raymond Benson’s The James Bond Bedside Companion.

The birth of the celluloid Bond began with a coincidental connection: Cuneo was the lawyer for another Fleming friend, the English financier Ivar Bryce, his partner in NANA. Bryce had recently tried his luck as a movie producer; in 1958 he financed The Boy and the Bridge, the first effort of the Irish filmmaker Kevin McClory. Looking for a follow-up, Bryce and McClory proposed to Fleming that they make an original James Bond movie, featuring eye-catching tropical settings and exciting underwater escapades.

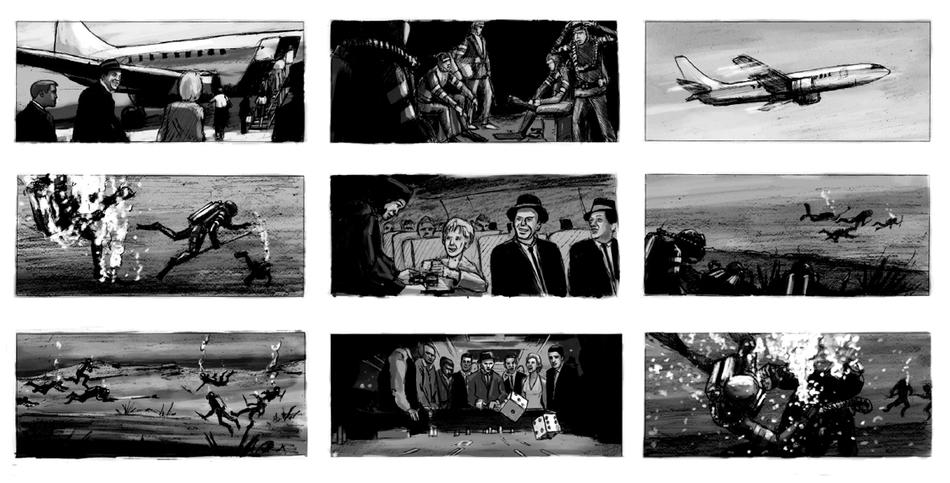

At a meeting in 1959, Fleming, Cuneo, Bryce, and McClory batted around ideas. In a memo dated May 28, Cuneo distilled their discussion into “a basic plot, capable of great flexibility.” Here are verbatim excerpts from Cuneo’s breakdown:

P.1. Bond is called to British Chief’s Office, M’s, and informed that mysterious radio signals are picked up by a British picket submarine on the D.E.W. [Distant Early Warning] Line, sent from an airplane. Oddly, the only airplane in area is a U.S.O. troupe of British American players on their way to entertain Allied Forces in an advanced U.S. arctic air base ...

P.5. Bond discovers baggage sergeant on U.S.O. plane is top enemy agent, and that one of the trunks is a shortwave radio transmitter ... Bond discovers also sergeant is field man on diabolical plot to explode American A bombs on their bases ...

P.7. British-American Intelligence is electrified when spy-sergeant puts in for transfer to Caribbean U.S.O., and marks his base preference, Nassau. His request is, of course, instantly granted. Nassau is about to fete U.S. Marines on their first scene of action. Miami entertainers will fly over for the evening — biggest U.S. show names.

P.8. Bond discovers (now in civvies) that a mysterious new company has ordered a fleet of Bahamian fishing boats — for Iron Curtain country — with very peculiar hulls for Grand Abaco trawlers. He studies plans, and discovers that hulls of new small vessels would be water tight — even if trapdoor opened from bottom of ship. A-bombs are to be delivered from enemy subs ...

P.11. CLIMAX: As Frank Sinatra, Milton Berle, Diana [sic] Shore, etc. etc., pile into plane to take them to Nassau from Miami, British frogmen are dressing for battle. Contrast is maintained throughout underwater fight in Nassau harbour: light and gaiety at the Casino and death struggle under water 100 yards away ...

The outline was a far cry from the eventual patented 007 formula. At one point, Cuneo suggested that our hero pretend to be a USO entertainer as his cover (“Bond’s efforts to imitate until he finds his métier can be amusing”). Still, Fleming wrote in a memo that Cuneo’s work — the first-ever outline for a James Bond movie — was “first-class” with “just the right degree of fantasy.” Over the ensuing months, Fleming refined it with McClory and screenwriter Jack Whittingham, even venturing that Cuneo should play the chief villain, Largo, because “he has a more fabulous gangster face than has ever been seen on the films.”

Unfortunately, the necessary financing never came through. For that reason, as well as his growing distrust of the mercurial McClory, Cuneo sold his rights to the memo to Bryce for one dollar.

And there things might have rested had not Fleming appropriated much of the material for his ninth Bond book, Thunderball (which he dedicated “To Ernest Cuneo — Muse”). Following a messy legal battle, in which McClory won the film rights to the book, Thunderball became the fourth Bond movie, in 1965. Five writers received onscreen credit. Cuneo was not among them.

“I think he would just laugh it off,” said Cuneo’s son, Jonathan ’74CC, an attorney in Washington, DC. “He was always giving things away for a dollar. For him it was easy come, easy go.”