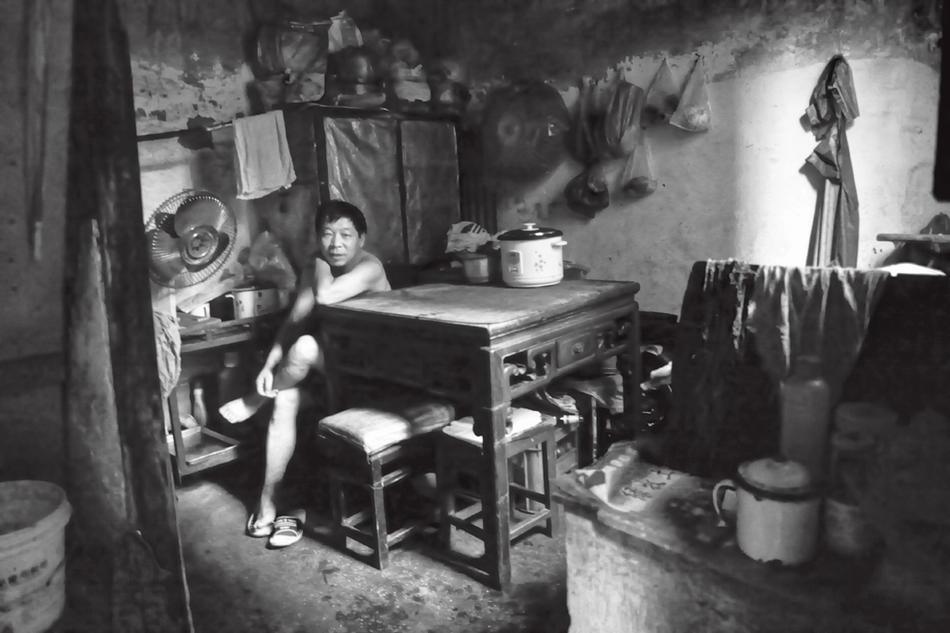

Howard French stands in a narrow alley, peering down into the black box of an apparatus that dangles from his neck at waist level. The apparatus resembles a cross between a miniature traffic signal and an old stereo speaker. French sees, through the box, a perfect square image: peeling walls, parked bikes, shuttered windows, hanging laundry, and, just outside a doorway, a shirtless man in sandals.

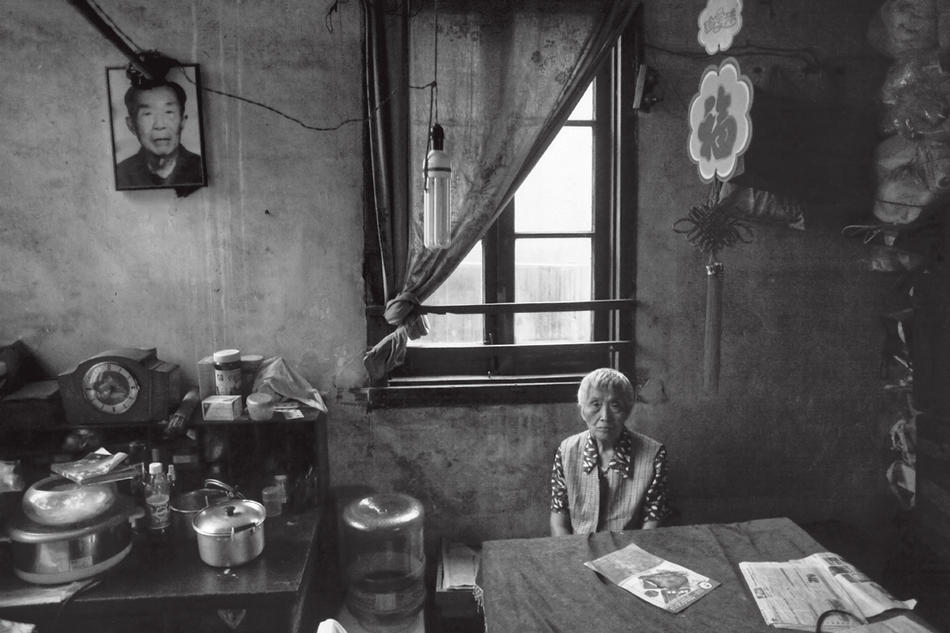

“A lot of my work is centered on a notion of intimacy, and of entering what I think of as the real private world of my subjects,” says French, a former New York Times reporter and, since 2008, associate professor of journalism at Columbia. “You won’t find pictures of mine where people are posing for the camera or, generally speaking, responding to my presence.”

French is tall and thin, with the solemn, searching air of a traveler who has landed peacefully on this planet to observe and chronicle how we live. He grew up in Washington, D.C., spent college summers in Ivory Coast (his father was a doctor with the World Health Organization), has lived on four continents, speaks seven languages, and seems, in his composed, penetrating manner, to have universalized himself into a spectral eyeball. He meets you on his ground, which, you soon find, is your ground, too: a relaxed but serious place where human beings can make inquiries and learn.

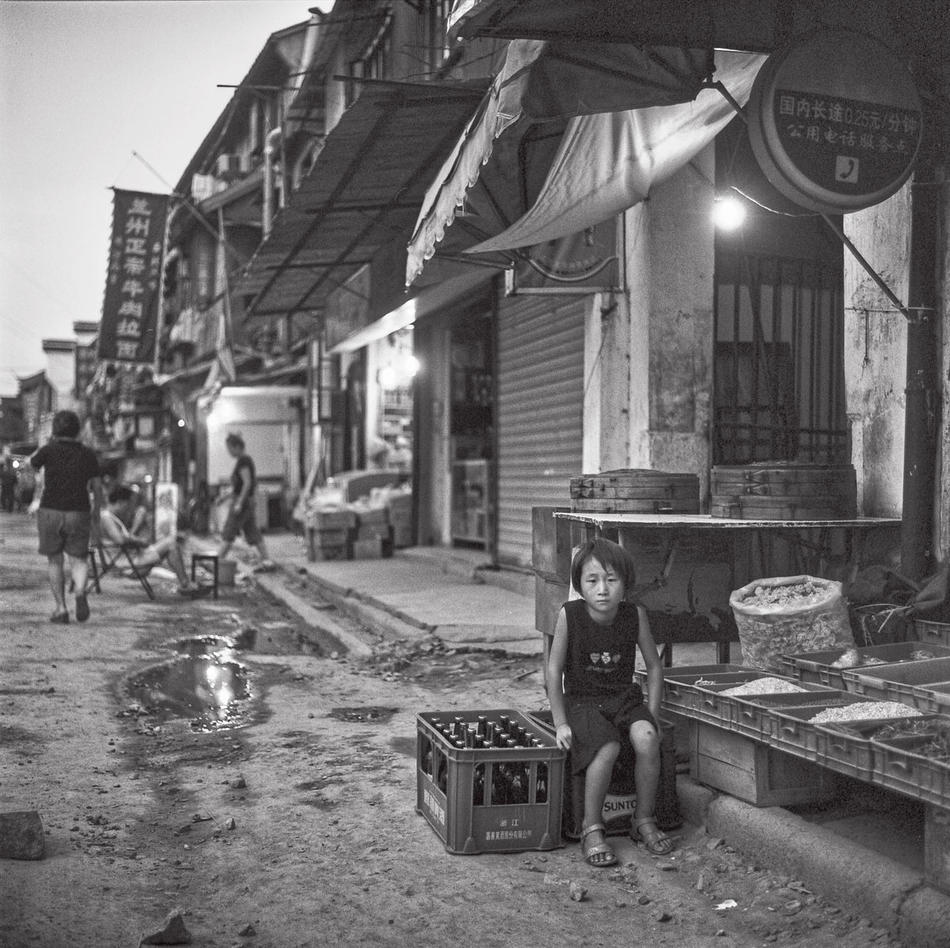

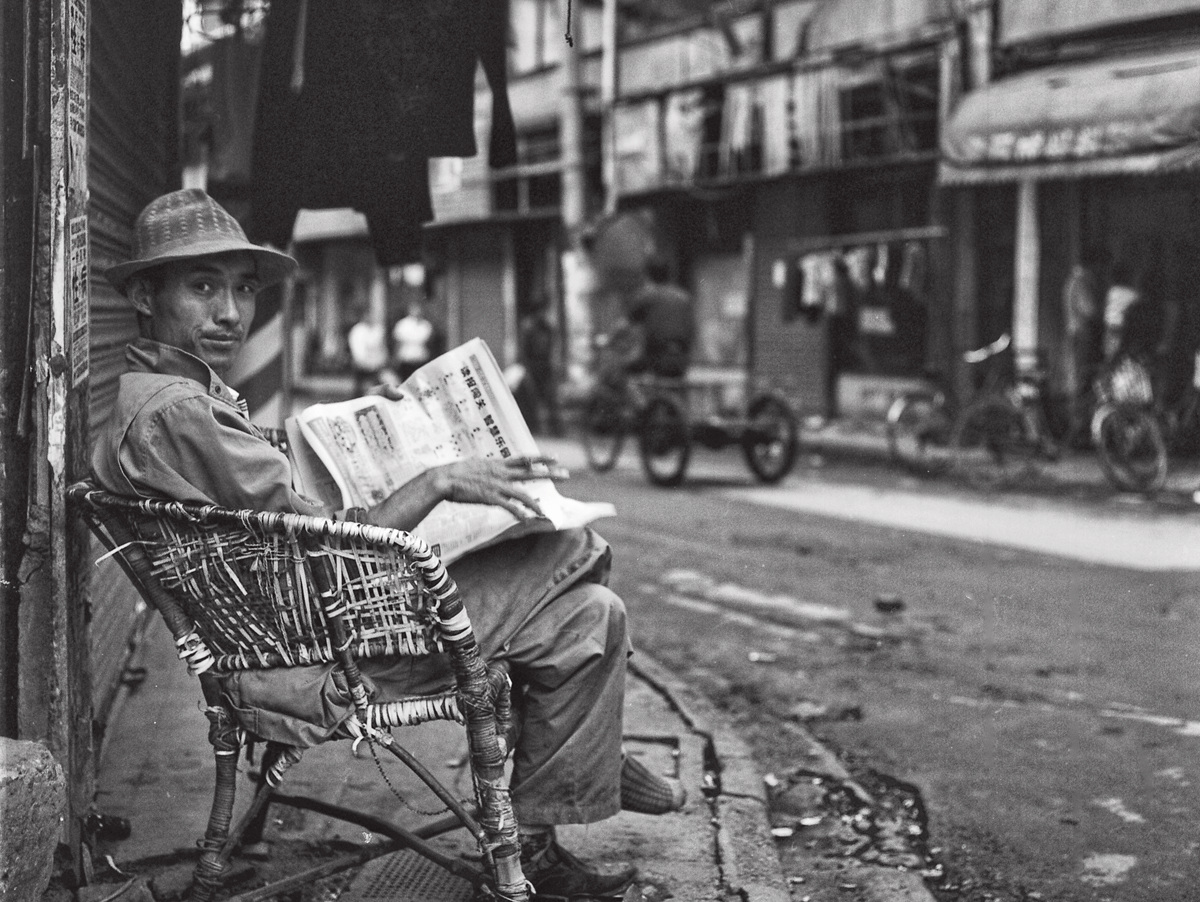

In 2003, the Times sent French to China to be its Shanghai bureau chief. French spent his first six months in Shanghai immersed in language study. The daily training was so rigorous and exhausting that French, seeking escape from the thickets of speech, did what came naturally: He began wandering the streets during his off-hours with his 1956 Rolleiflex camera. He loves the Rolleiflex, which produces a distinctive square frame and has manual functions that require slow, deliberate operation. Over the next five years, French haunted the alleys of Shanghai, discreetly recording a vanishing way of life.

In 2009, back in New York, French showed his street pictures to his friend and mentor, the photographer Danny Lyon, who advised French to take his notion of intimacy a step further by entering people’s homes. French agreed. That summer, he returned to Shanghai with his Canon 5D Mark II, a digital camera that responds well to low light and doesn’t require a flash. For three months, French knocked on doors, gaining deeper entry into those private worlds.

“When I walk outside with a camera in my hand, I’m a different person,” French says. “My head is screwed on in a different way, and it’s almost a personality change. I’m not casually out with a camera; I’m there to take pictures. From this has grown a sense of license, or authority. There’s no question in my mind of whether what I’m doing is OK, or what people are going to think about it.”

French, who got his first camera as a child from his father, has long been acquainted with the privileges conferred by the press badge. Over his 22-year career at the Times, he wrote dispatches from Red Hook and Rwanda, Port-au-Prince and Pakistan, Tokyo and Tanzania, empowered in his role of newsperson to ask strangers incisive questions. It’s a mode that translates well to his photography.

“The process feels very similar to me,” says French, who at the J-school teaches a course on reporting in China and another on reporting in the developing world, with an emphasis on Africa. “As a journalist, I don’t just randomly walk down the street interviewing people. I go out with an idea of a particular mission. I have a sense, even if I am open to surprise, of what kind of characters will be the most interesting for my purposes, and how best to approach them in order to gain access. Up until that point, I see journalism and photography as being very alike. You have to overcome a lot of the same hurdles.

“One of the biggest impediments to journalism students is something simple that most of them never stopped to think about before they got here, and that is: How do you actually approach somebody? How do you start a conversation? How do you break the ice? How do you gain someone’s confidence? Documentary photography requires every single one of those skills. You might even say it demands them at a higher degree.”

To prepare for a project like Disappearing Shanghai, French walks around. He figures out the traffic patterns, studies the light, marks the human scene. And he never hides his camera: It is always out, because the sooner people become accustomed to it, the sooner he can start to work.

“If I spring it on you, you are going to throw your hands up as if you have been assaulted. So I walk around with my camera totally visible, making no bones about what I’m doing or who I am. All of this happens before the serious work begins.

“A lot of these more intimate Shanghai pictures came about as a result of what can only be called the ‘power of lingering.’ I can walk up to you — you’re a stranger hanging out on a street corner or sitting on a park bench or eating your dinner or sitting in front of your house — and initially, because I’m very tall and don’t look at all Chinese, perhaps you are uneasy.

“I’ll stand five feet away from you. If I have to stand there for an hour, I’ll stand there for an hour. And eventually you will think, ‘This person who I was really curious about when he first walked up is now just part of the landscape. He has been here for an hour now, shifting from one foot to the other, daydreaming. I don’t need to be too concerned with him.’ So I’ve blended into the environment, even though I am as alien as I could be. And when I feel the temperature is just right, I take my picture.”

Last summer, at one of China’s two international photo festivals, French exhibited his black-and-white landscapes of a part of Virginia where his ancestors were slaves. He also spent a month taking pictures and teaching photography to photojournalists in Burma, an extremely isolated and restrictive country for which he had to work hard to obtain a visa. Currently, he’s collaborating on a book of his Shanghai photos with the Chinese novelist and poet Qiu Xiaolong.

“One striking quality about Howard’s Shanghai pictures is that they’re not just about a building or the lane or the alley or the small side streets,” says Qiu, who grew up in that rapidly changing city. “It’s also about the culture and people associated with these streets. Nowadays, if you go to China, and Shanghai especially, you will see a lot of pictures of modern or postmodern buildings. Howard captures the traditional Shanghai that is disappearing.”

That’s more than French himself might offer. As a writer who has published thousands of articles and a book called A Continent for the Taking: The Tragedy and Hope of Africa, and who has completed his first novel and recently won an Open Society Fellowship to research a book on Chinese migration to Africa, French understands the limits of words.

“Having worked for five years on Disappearing Shanghai, I don’t feel I need to tell people what it means,” he says. “The whole purpose is for the pictures themselves to speak.”