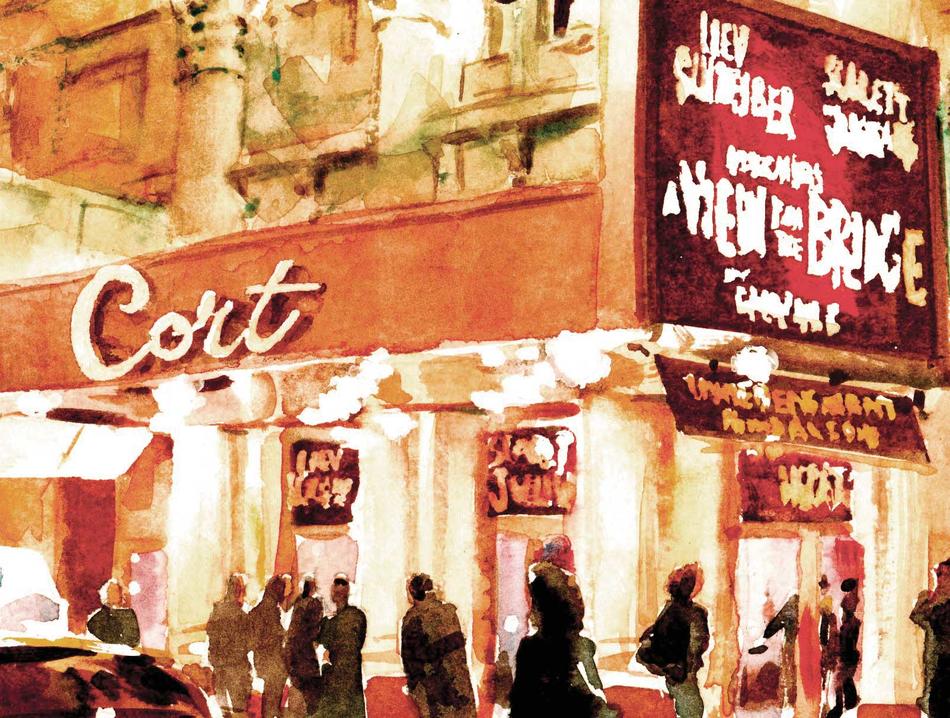

As I wedged my way into the lobby of the Cort Theatre in Manhattan minutes before the final preview of A View From the Bridge, I ran into a lean figure in jeans, cloth overcoat, and wool hat. I figured he must have been a stagehand. Then the man turned, and I saw the wire-rim glasses and ruddy face and realized I was looking at the play’s director, Gregory Mosher.

It would be hard to think of a more unassuming pose for a world-class theater artist on such a crucial evening. On Broadway, the last few previews are more important than opening night. While the party and paparazzi wait for the official premiere, the critics watch these performances to get an early start on writing their notices.

This production of Bridge, Arthur Miller’s McCarthy-era parable of a longshoreman consumed by jealousy, was the second on Broadway in nearly 30 years for a play generally not ranked among the author’s greatest. It marked the Broadway debut of Scarlett Johansson, playing opposite the stage veteran Liev Schreiber. The real-time demands of the theater had exposed the weaknesses of many a movie star in the past.

Now, with so much at stake, Mosher was hanging incognito on the periphery. Most directors would enjoy being recognized, and even expect it. Mosher, though, genuinely preferred a kind of invisibility. He has always been about the play.

“To be a writer’s director,” Mosher put it to me recently, “is to trust that what you need to direct is on the page, and to have the discipline to try — and, man, it is hard — to fulfill the writer’s intentions, not yours. The main reason to devote your energy to discovering the play is that the play’s ideas are more complicated and interesting than any idea you could have about it.”

I met Mosher in 1984, when he directed the Broadway premiere of Glengarry Glen Ross, the black comedy about real estate sharks by David Mamet. Mosher and Mamet had collaborated many times already at Chicago’s Goodman Theatre, but when Glengarry came to New York, it encountered a sort of Broadway haughtiness, even disdain. Just what could be so terrific, the whispering went, about this no-name director and his no-name cast from the provinces? Mosher had decided against stars like Paul Newman and Al Pacino in favor of an ensemble of Goodman regulars, several of whom had taken up acting as a midlife second career. After rave reviews and a Pulitzer Prize, the dismissive sniffs vanished, and theater people in New York were enviously asking what was so magical about Chicago.

With that query in mind, the Times dispatched me in March 1985 to the Goodman while Mosher was directing Mamet’s adaptation of The Cherry Orchard. We spent a lot of time talking about Studs Lonigan, the great and long-forgotten trilogy by James T. Farrell about Chicago’s Irish Catholic working class. Mosher had an appreciation for a novel that was earthy and tough and a million miles from hip. The kind of theater that Mosher and Mamet created at the Goodman was true to the literary tradition of Farrell.

Mosher came to New York in August 1985, hired to resuscitate the two nonprofit theaters at Lincoln Center, the Mitzi E. Newhouse and the Vivian Beaumont, which had been almost entirely dark for the preceding four years. Their previous artistic director, Richmond Crinkley, had claimed that, architecturally, the venues were not viable. Dubious though Crinkley’s contention was, the Lincoln Center theaters had in the past defied even the legendary Joseph Papp.

In short order, Mosher had both theaters lit and busy, and his tenure at Lincoln Center saw the “Woza Afrika!” festival of South African plays, a splendid revival of John Guare’s House of Blue Leaves, and more Mamet.

Over the past five years, Mosher, who is Professor of Professional Practice in Theater Arts at Columbia and director of the Columbia Arts Initiative, has brought Peter Brook and Václav Havel to the University. Through the Arts Initiative, he also has continued a personal tradition begun at the Goodman and Lincoln Center: making theater affordable to students. “The $10 tickets were for everyone, not just students,” Mosher recalled. “But the idea is the same — where are the next audiences coming from? Columbia is a part of that search.”

With A View From the Bridge, Mosher has supplied an ideal destination for that search. I’ve seen probably 350 plays in my lifetime, and I have powerful memories of the 1983 revival of Bridge with Tony Lo Bianco. Yet, when the curtain came down on the final preview of Mosher’s production, I looked at my three companions and we all gasped; Bridge was that good. The stars stayed in character; every supporting role, large or small, had hand-tooled specificity; and the director’s fierce attention to word and action, especially the currents of sexual tension, saved Miller from his own weakness for preachiness.

Two mornings later, when the reviews appeared, Mosher remained nearly as inconspicuous as he’d been in the lobby that night. Ben Brantley in the New York Times and John Lahr in the New Yorker led a unanimous chorus of praise. They extolled the cast — Schreiber, Johansson, Jessica Hecht, Michael Cristofer — and they upwardly revised their opinion of the 50-year-old play.

As for the director, he received maybe a clause. Which, I suspect, was for Mosher, just the right proportion.