Academics in the field of the humanities expect to disappear behind the material they explicate, summarize, or translate. Donald Keene ’42CC, ’49GSAS, ’97HON is an exception. He has, in the best sense of the phrase, led a double life. In the United States and elsewhere in the West, he is known as a distinguished scholar and translator. (At Columbia he is also Shincho Professor of Japanese Literature and University Professor Emeritus.) In Japan he is a celebrity, perhaps the only American with an interest in Japanese culture who is known to most Japanese. The fact that his memoirs were serialized in Japan’s biggest newspaper gives us a hint of this. It is this double Keene that Chronicles of My Life: An American in the Heart of Japan reveals to us, artlessly, and with considerable tact and enthusiasm.

I was a student of Donald Keene at Columbia more than 30 years ago, and I was particularly interested in the first few chapters of this brief and disarming memoir since I knew relatively little about his early years. He describes his upbringing in New York and his time as a Columbia College student, where he took Humanities with Mark Van Doren. “Van Doren had little use for commentaries or specialized literary criticism,” Keene writes. “Rather, the essential thing, he taught us, was to read the texts, think about them, and discover for ourselves why they ranked as classics. Insofar as I have been a success as a teacher of Japanese literature, it is because I had a model in Mark Van Doren.”

Keene arrived at Columbia in September 1938, a few weeks before the Munich Agreement was signed. His dread of war and his acceptance of its growing inevitability during his undergraduate years are movingly told, as is the epiphany late in 1940 that led him toward a lifelong encounter with Japan. “[A]t the worst point of the conflict within me between my hatred of war and my hatred of the Nazis, a kind of deliverance came my way,” he writes. He was browsing in a bookshop in Times Square and picked up a remainder copy of Arthur Waley’s translation of The Tale of Genji. Keene was bitten. “Until this time I had thought of Japan mainly as a menacing militaristic country,” he recalls. The 11th-century novel became a “refuge from all I hated in the world around me.”

The world he hated closed in on him with the attack on Pearl Harbor. Keene attended the Navy Japanese Language School in California and spent the balance of the war in the Pacific translating documents found on captured Japanese soldiers. He managed by subterfuge to get to Tokyo at the end of the war, where he spent a week among the bombed ruins and, remarkably, tried to find the families of some of the prisoners he had interrogated.

These first encounters with Japanese citizens — not the highly educated and sophisticated friends he would come to make later — help us to understand one secret that has given Keene his ability to penetrate so deeply into Japanese culture. Although he never says so, it is obvious that he treated these prisoners with the same kind of consideration and respect that he would any other fellow human being. That kind of democratic spirit can be quickly felt, conveyed across cultures, even without words.

For some readers in the U.S., the memoir may seem at first to lack some necessary detail about Japan’s postwar cultural background that might provide a context in which to place Keene’s observations. But even a cursory reading of the text suggests a number of aspects of Japanese history and culture that were important during the period Keene describes. The first of them is the fact that, in Japan from the 1950s through the 1990s, at least, literature was still regarded as a central means to convey important aspects of Japanese culture from one generation to the next (although I would hesitate to say that assumption can be carried on into these days of manga and anime).

The second assumption concerns the need of Japanese artists and intellectuals to rejoin, and with honor, the larger artistic and intellectual worlds from which they had been cut off for some many years by the war. Japanese readers and writers, whatever their political persuasions, strove to reassert themselves and be taken seriously by their peers in Europe and the U.S. Given the complexities of their history and the difficulties of the Japanese language, Keene, with his taste, linguistic skill, and knowledge, was to prove a superior and even-handed interpreter of Japan to the West. Without compromising his own artistic and cultural convictions, he quickly came to know the realities and challenges of contemporary life in Japan, and he was able to identify and explicate for his readers both in Japan and in the U.S. some of the contributions of the Japanese tradition as he saw it.

Chronicles of My Life suggests the presence of still another narrative as well: the discovery of Japanese literature by American readers. At the end of World War II, there was relatively little Japanese literature widely available in English, other than Waley’s Tale of Genji and his version of the Pillow Book of Sei Shônagon, both written in the Heian period, about 1000 years ago. By the early 1950s, Keene had produced translations of two of the most important novels written in the early postwar period, both by Dazai Osamu, and Keene’s two anthologies of Japanese literature, one classic, one modern, revealed to the reader for the first time the range and richness of the long Japanese tradition. Many other translators, quite a number of them trained by Keene himself, have since made available a wide variety of texts from every period. Because of such efforts, it was possible by 1968 for a Japanese writer, Kawabata Yasunari, to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, followed by Kenzaburô Ôe in 1994.

Readers familiar with the novels of such now well-known modern masters as Kawabata, Tanizaki, Mishima, Kôbô Abe, and Ôe will enjoy Keene’s memories of these men. Thanks to Keene, and others, Japanese literature entered a wider world.

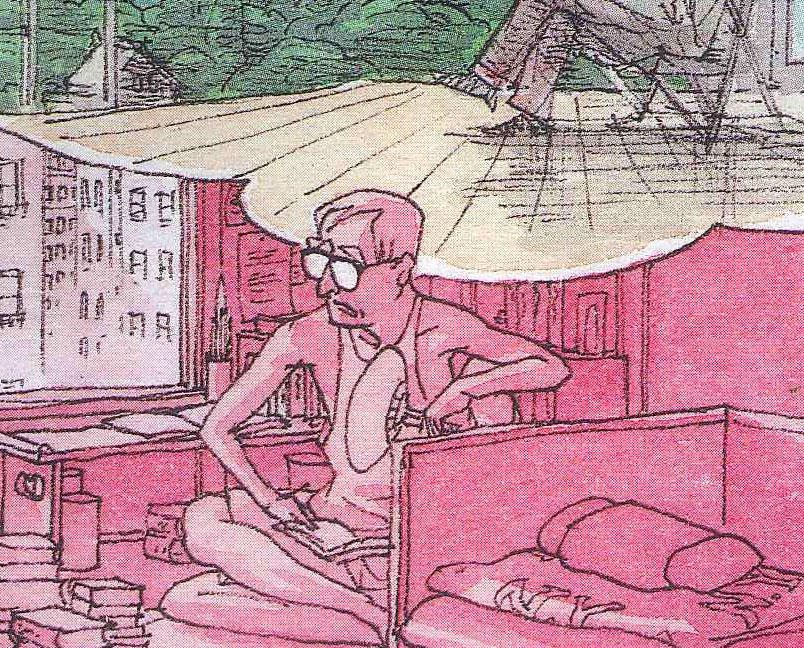

Chronicles of My Life is a beautifully produced book. Most striking are the charming illustrations by one of Japan’s top younger artists, Akira Yamaguchi, which were commissioned by the Yomiuri Shimbun, the newspaper in which Keene’s memoirs first appeared in weekly installments. Yamaguchi’s paintings bear close and repeated inspection in order to savor the artist’s subtle attitudes toward Keene’s account. The book should have included some information about Yamaguchi, as he has a considerable reputation in Japan.