Introduction by Wm. Theodore de Bary

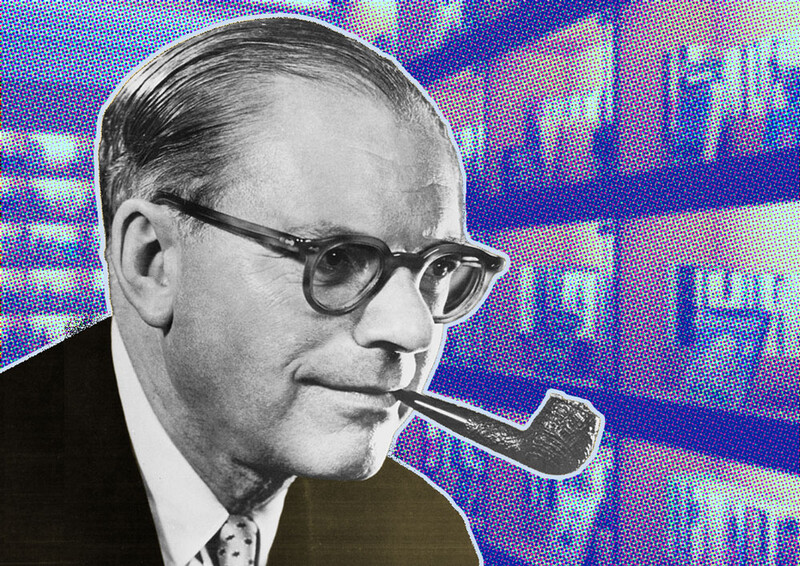

Richard Hofstadter’s stature, not only as a leading American historian but as a public intellectual who represented Columbia at its best in his time, is shown by the extraordinary honor done him when he was asked to give the commencement address in the spring of 1968. It is a long tradition at Columbia that the president, not an invited speaker, always gives this address himself. The sole exception was made in favor of Hofstadter, who in that year of radical challenge to the values of the University, stood firmly and spoke eloquently in their defense.

The story of the dominant figure in American historical writing in the post–World War II years is told by his successor to the distinguished DeWitt Clinton Professorship of American History, Eric Foner, who received his doctorate at Columbia under Hofstadter. Foner’s publications have focused on the intersections of intellectual, social, and political history with special regard to race relations.The latest of his many award-winning books are Who Owns History? Rethinking the Past in a Changing World and Give Me Liberty! An American History.A winner of the Great Teacher Award from the Society of Columbia Graduates, Foner is an elected member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and of the British Academy. He has served as president of the Organization of American Historians and as president of the American Historical Association.

Wm. Theodore de Bary ’41CC, ’53GSAS, ’94HON is John Mitchell Mason Professor of the University and provost emeritus of Columbia University.

A remarkable number of prominent historians have taught at Columbia over the years, but probably none can match Richard Hofstadter in the enduring impact of his scholarship. A child of the Great Depression, he earned his master’s and doctoral degrees and then taught here from 1946 until his untimely death in 1970. Despite the brevity of his career, Hofstadter left a prolific body of work, remarkable for its range, originality, and readability. Because of his penetrating intellect and sparkling literary style, Hofstadter’s writings continue to exert a powerful influence on how scholars and general readers alike understand the American past.

“All my books,” Hofstadter wrote in the 1960s,“have been, in a certain sense, topical in their inspiration. That is to say, I have always begun with a concern with some present reality.” Although often identified as the chief practitioner of the “consensus” history of the 1950s, Hofstadter, in fact, exhibits no single approach or fixed ideology in his writings. His approach to the American past changed several times during his career, reflecting his evolving encounter with the turbulent times in which he lived.

Richard Hofstadter was born in 1916 in Buffalo, New York, the son of a Jewish father and a mother of German Lutheran descent.As for so many others of his generation, Hofstadter’s formative intellectual and political experience was the Great Depression. Buffalo, a major industrial center, was hard hit by unemployment and social dislocation. The Depression, he later recalled, “started me thinking about the world. . . . It was as clear as day that something had to change. . . .You had to decide, in the first instance, whether you were a Marxist or an American liberal.” As an undergraduate at the University of Buffalo, Hofstadter gravitated toward a group of left-wing students including the brilliant Felice Swados, whom he later married.

The Hofstadter who arrived in New York City in 1936 was, as Alfred Kazin later recalled, “the all-American collegian just in from Buffalo with that unmistakable flat accent.” At his father’s insistence he first enrolled in the Columbia Law School but soon transferred to the Department of History. For a time, the Hofstadters became part of New York’s broad radical political culture in the era of the Popular Front.He was briefly a member of the Communist party, although he “eased himself out” early in 1939. There followed a rapid and deep disillusionment — with the party (run by “glorified clerks”), the Soviet Union (“essentially undemocratic”), and eventually with Marxism itself.

Although Hofstadter mostly abandoned active politics after 1939, his earliest work as a historian reflected his continuing intellectual engagement with radicalism. His Columbia master’s thesis, completed in 1938, showed how the benefits of New Deal agricultural policies in the South flowed to large landowners, while the conditions of sharecroppers — black and white — only worsened. The essay’s critical evaluation of FDR, a common attitude among New York radicals, would persist in Hofstadter’s writings long after the political impulse that inspired the thesis had faded.

As with many others who came of age in the 1930s, Marxism framed Hofstadter’s general intellectual approach, but in application to the American past the iconoclastic materialism of Charles A. Beard was his greatest inspiration. Beard taught that American history had been shaped by the struggle of competing economic groups, primarily farmers, industrialists, and workers. A dialogue with the Beardian tradition shaped much of Hofstadter’s subsequent career.

While Beard devoted little attention to political ideas, Hofstadter soon became attracted to the study of American social thought. He once identified himself as “a political historian mainly interested in the role of ideas in politics, an historian of political culture.” His interest was encouraged by Merle Curti, a Columbia professor with whom Hofstadter by 1939 had formed, according to his wife, a “mutual admiration society.”Aside from his relationship with Curti, however, Hofstadter was not particularly happy at Columbia. For three years running, he was refused financial aid and was gripped by a sense of unfair treatment. Nonetheless, under Curti’s direction, Hofstadter completed his dissertation, Social Darwinism in American Thought, published by the University of Pennsylvania Press in 1944.The book focuses on the late 19th century and ends in 1915, the year before Hofstadter’s birth. But, as he later observed, the “emotional resonances” that shaped its approach were those of his own youth, when conservatives used such Darwinian ideas as natural selection, survival of the fittest, and the struggle for existence to reinforce conservative, laissez-faire individualism. Hofstadter made no effort to disguise his distaste for the Social Darwinists or his sympathy for the critics, especially the sociologists and philosophers who believed intellectuals could guide social progress (views extremely congenial to Hofstadter at the time he was writing).His heroes were early-20th-century philosophers like John Dewey, whom he presented as a model of the socially responsible intellectual, an architect of a “new collectivism” in which an activist state would improve society.

Lively and Lucid

Hofstadter’s first book displayed qualities that would remain hallmarks of his subsequent writing, among them an amazing lucidity in presenting complex ideas, the ability to sprinkle his text with apt quotes that make precisely the right point, and the capacity to bring past individuals to life in vivid, telling portraits.To the end of his life, Hofstadter’s writings would center on Social Darwinism’s underlying themes — the social context of ideologies and the role of ideas in politics.

If Social Darwinism announced Hofstadter as one of the most promising scholars of his generation, his second book, The American Political Tradition, published in 1948, propelled him to the very forefront of his profession. He began writing this brilliant series of portraits of prominent Americans in 1943, while teaching at the University of Maryland. In 1946, a year after his wife’s death from cancer, he returned to Columbia’s History Department as an assistant professor.An enduring classic of American historical writing, The American Political Tradition remains today a standard work in college and high school history classes and has been read by millions outside the academy. The writing is energetic, ironic, and aphoristic. Hofstadter’s brilliant chapter titles remain in one’s memory even after the specifics of his argument have faded: “The Aristocrat as Democrat” (Jefferson), “The Marx of the Master Class” (Calhoun), “The Patrician as Opportunist” (FDR).

Providing unity to the individual portraits was Hofstadter’s insight that his subjects held essentially the same underlying beliefs. Instead of persistent conflict between agrarians and industrialists, capital and labor, or Democrats and Republicans, broad agreement on fundamentals, particularly the values of individual liberty, private property, and capitalist enterprise, marked American history. “The fierceness of the political struggle,” he wrote,“has often been misleading; for the range of vision embraced by the primary contestants . . . has always been bounded by the horizons of property and enterprise.”

With its emphasis on the ways an ideological consensus had shaped American development, The American Political Tradition marked Hofstadter’s break with the Beardian and Marxist traditions. Along with Daniel Boorstin’s The Genius of American Politics and Louis Hartz’s The Liberal Tradition in America (both published a few years afterward), Hofstadter’s second book came to be seen as the foundation of the “consensus history” of the 1950s. But Hofstadter’s writing never devolved into the uncritical celebration of the American experience that characterized much “consensus” writing. As Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., observed, there was a basic difference between The American Political Tradition and works like Boorstin’s: “For Hofstadter perceived the consensus from a radical perspective, from the outside, and deplored it; while Boorstin perceived it from the inside and celebrated it.”

In Hofstadter’s account, the domination of individualism and capitalism in American life produced not a benign freedom from European ideological conflicts but a form of intellectual and political bankruptcy, an inability on the part of political leaders to think in original ways about the modern world. If the book has a hero, it is Wendell Phillips.Alone among Hofstadter’s subjects in never holding public office, Phillips was an engaged intellectual who used his talents first to mobilize opposition to slavery and then to combat the exploitation of labor in the Gilded Age. It is indeed ironic that Hofstadter’s devastating indictment of American political culture should have become the introduction to American history for generations of students.

If his first two books reflected “the experiences of the Depression era and the New Deal,” in the 1950s a different reality shaped Hofstadter’s writing — the Cold War and McCarthyism. At Columbia, Hofstadter found himself part of the world of the New York intellectuals. But this world had changed dramatically since the radical days of the 1930s. He had “grown a great deal more conservative in the past few years,”Hofstadter wrote in 1953. Hofstadter was repelled by McCarthyism, and in the early 1950s spoke at meetings and signed petitions against it. Hofstadter’s Historian and Columbia professor Charles Austin Beard ’04GSAS, ’44HON emphasized the role of economic life in shaping American history. He was Hofstadter’s formative inspiration understanding of McCarthyism as the outgrowth of a deep-seated American anti-intellectualism and provincialism reinforced a distrust of mass politics that had been simmering ever since he left the Communist party in 1939. After supporting with “immense enthusiasm” Adlai Stevenson’s campaign for the White House in 1952, Hofstadter retreated altogether from politics. “I can no longer describe myself as a radical, though I don’t consider myself to be a conservative either,” he later wrote. “I suppose the truth is, although my interests are still very political, I none the less have no politics.”

What Hofstadter did have was a growing sense of the fragility of intellectual freedom and social comity, and the conviction that historians needed new intellectual tools to explain political ideas and behavior. The Columbia environment powerfully shaped his intellectual development. Hofstadter became more and more interested in how insights from other disciplines could enrich historical interpretation.Three colleagues in particular influenced him. Lionel Trilling’s writing on the symbolic interpretation of literary texts suggested a new approach to understanding historical writings. Robert K. Merton’s work explored the distinction between the “manifest” and “latent” functions of political ideas and institutions. And C. Wright Mills explored the status anxieties of the middle class in modern society. Hofstadter and Mills shared an improbable friendship — temperamentally and politically, the Texasborn radical populist and the disillusioned New York intellectual could not have been more different.

These influences helped to make Hofstadter more and more sensitive to what he called the “complexities in our history which our conventional images of the past have not yet caught.” Reared on the assumption that politics essentially reflects economic interests, he now became fascinated with alternative explanations of political conduct: unconscious motivations, status anxieties, irrational hatreds, paranoia.

Hofstadter applied these insights to the history of American political culture in a remarkable series of books that made plain his growing sense of alienation from what he called America’s periodic “fits of moral crusading.” Having come of age in a political culture that glorified “the people” as the wellspring of democracy and decency in American life, he now portrayed politics as a realm of fears, symbols, and nostalgia and ordinary Americans as beset by bigotry, xenophobia, and paranoid delusions. The Age of Reform (1955) offered an interpretation of Populism and Progressivism “from the perspective of our own time.”The South’s downtrodden small farmers who had evoked sympathy in his master’s essay on sharecroppers under the New Deal now, as Populists of the late 19th century, appeared as prisoners of a nostalgic agrarian myth who lashed out against imagined enemies from British bankers to Jews in a precursor to “modern authoritarian movements.” He depicted the Progressives as a displaced bourgeoisie seeking in political reform a way to overcome its decline in status.

A similar sensibility informed Hofstadter’s next two books. Anti-Intellectualism in American Life (1963), written, Hofstadter wrote, as a “response to the political and intellectual conditions of the 1950s,” described an American heartland “filled with people who are often fundamentalist in religion, nativist in prejudice, isolationist in foreign policy, and conservative in economics” as a persistent danger to intellectual life. Frightened by the Goldwater campaign of 1964, Hofstadter brought together a group of essays in The Paranoid Style in American Politics (1965), which suggested that belief in vast conspiracies, apocalyptic fantasies, and heated exaggerations characterized popular enthusiasms of both the right and the left.

Two, Too Much

The Age of Reform and Anti-Intellectualism won Hofstadter his two Pulitzer Prizes. Ironically, however, both books today seem more dated than his earlier books. Their deep distrust of mass politics and their apparent dismissal of the substantive basis of reform movements strike the reader, even in today’s conservative climate, as exaggerated and elitist. Historians have shown the Populists to be far more perceptive in their critique of late-19thcentury capitalism than Hofstadter allowed, and they have expanded the portrait of Progressivism to encompass labor unions, women’s suffrage activists, and others far beyond the displaced urban professionals on whom Hofstadter concentrated. Nonetheless, as the historian Robert Kelley has written, these works had a powerful influence on the study of American political history: “They taught us to think not only of socioeconomic class, but of specific cultural milieux in which particular moods and world views are generated. Out of this came a new sensitivity to the power of the irrational, to tendencies among political groups to be swayed by concerns over status and by paranoid beliefs.”

As social turmoil engulfed the country in the mid-1960s, Hofstadter remained as prolific as ever, but his underlying assumptions shifted again. In The Progressive Historians (1968), he attempted to come to terms once and for all with Beard and his generation.Their portrait of an America racked by perennial conflict, he noted, was overdrawn, but by the same token, the consensus outlook could hardly explain the American Revolution, Civil War, or other key periods of discord in the nation’s past (including, by implication, It is indeed ironic that Hofstadter’s devastating indictment of American political culture should have become the introduction to American history for generations of students. American Violence (1970), a documentary volume edited with his graduate student Michael Wallace, offered a chilling record of political and social turbulence that utterly contradicted the consensus vision of a nation placidly evolving without serious disagreements. Finally, in America at 1750, Hofstadter offered a bittersweet portrait that brilliantly took account of the paradoxical coexistence of individual freedom and widespread social injustice in the Colonial era. This pioneering work came to be called the “new social history.” Hofstadter’s canvas now included slaves and indentured servants as well as the political leaders, small farmers, professionals, and businessmen on whom he had previously concentrated.The book remained unfinished at the time of his death from leukemia in 1970. America at 1750 was to have been the first in a three-volume general history of the United States.

History Writ Small

It was during the 1960s that I came to know Richard Hofstadter. He supervised my senior thesis at Columbia College in 1963 and later directed my dissertation. At this time, the Depatment of History was still divided into a graduate and an undergraduate branch, the former with offices in Fayerweather, the latter in Hamilton. Hofstadter taught mainly graduate courses but chose to keep his office in Hamilton (perhaps, as one of his former colleagues recently speculated, because there had been opposition to his receiving tenure and he was grateful for the strong support of Harry J. Carman, dean of the College).

For all his accomplishments, Hofstadter was utterly without pretension. Nor did he try to impose his own interests or views on his students. If no Hofstadter school emerged from Columbia, it was because he had no desire to create one. Indeed, it often seemed during the 1960s that his graduate students, many of whom were actively involved in the civil rights and antiwar movements, were having as much influence on his evolving outlook as he on theirs.

Among the department’s American historians at this time were some brilliant While Hofstadter delivered the commencement address to the class of 1968 inside the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, some graduates walked out in protest and staged a “countercommencement.” Hofstadter did have . . . a growing sense of the fragility of intellectual freedom and social comity . . . lecturers — the witty, incisive William Leuchtenberg, the deeply thoughtful Eric L. McKitrick, the spellbinding Walter P. Metzger, and the legendary James P. Shenton, beloved by generations of undergraduates. Hofstadter was not a great lecturer — writing was his passion. He was at his best in small seminars and individual consultations.

Devoted to the idea of the University as a haven of scholarly discourse in a culture beset by irrationality and threats to academic freedom, Hofstadter was shaken by the upheaval of 1968, although he remained close to those of his graduate students who were involved. When asked to deliver the commencement address in place of President Grayson Kirk in May of that fateful year, he agreed. He knew that some of his students would sharply criticize him for lending his name to what we considered a discredited administration.“ If I don’t do it,” Hofstadter told me, “someone far worse will.” The ceremony was held in the Cathedral of St. John the Divine.When Hofstadter rose to speak, many of the graduating seniors departed for a “countercommencement” on Low Plaza.Those who remained heard a short, eloquent speech reaffirming the University’s commitment to “certain basic values of freedom, rationality, inquiry, and discussion.”He ended by asking whether the University could go on. “I can only answer: How can it not go on? What kind of people would we be if we allowed this center of our culture and our hope to languish and fail?”

Shortly before his death, Newsweek published an interview with Hofstadter, a melancholy reflection on a society confronting a “crisis of the spirit.” Young people, he said, had no sense of vocation, no aspirations for the future. Yet the causes of their alienation were real:“You have a major urban crisis.You have the question of race, and you have a cruel and unnecessary war.” He rejected students’ stance of “moral indignation” as a kind of “elitism” on the part of those who did not have to face the day-to-day task of earning a living. Ultimately, he went on, it was American society itself, not just its children, that had to change.“I think that part of our trouble is that our sense of ourselves hasn’t diminished as much as it ought to.” The United States, he seemed to be saying,would have to accept limitations on its power to shape the world.The stultifying official consensus he had explored in The American Political Tradition would finally have to end.

From Social Darwinism to America at 1750, all Hofstadter’s books reflected not only a humane historical intelligence but an engagement with the concerns of the times in which he wrote. It is impossible to say what his intellectual trajectory might have been had he not died so young. As C. Vann Woodward said at the memorial service, “It seems almost unkind to speak of Richard Hofstadter as a fulfilled historian — when he was cut down so cruelly in his prime.” But his writings remain a model of what historical scholarship at its finest can aspire to achieve.

Eric Foner is the DeWitt Clinton Professor of American History at Columbia, the chair once occupied by Richard Hofstadter.