Someone should make a documentary about Dick Hyman ’48CC. Here’s the pitch: a young, white, mild-mannered pianist, possessed of an almost superhuman ability to play anything, finds himself in the thick of the raging jazz world of postwar New York; and while eluding classification — no one can really pin him down — he leads a career as long, varied, and colorful as any in American music.

The film’s soundtrack would be drawn, naturally, from Hyman’s wide-ranging oeuvre, which is really the soundtrack of 20th-century America: ragtime, stride, boogie-woogie, swing, bebop, rock and roll, bubblegum pop, elevator Muzak, soap-opera organ swells, game-show schmaltz, space-age electronica. The visuals would be equally evocative — photographs and newsreels from the ragtime era to the Jazz Age to the Great Depression, along with split-screen shots of Hyman and the piano giants whose styles he is able to replicate: Jelly Roll Morton, Fats Waller, James P. Johnson, Teddy Wilson, even Art Tatum, whom Rachmaninoff regarded as the greatest pianist in any style. Then there’s that priceless television kinescope from 1952, which Dick explains in his eloquent, understated way: “I played on a local show on the DuMont network that aired every evening, called Date on Broadway, and one night the guests were Earl Wilson, the Broadway columnist, introducing Leonard Feather, the jazz writer, presenting the Esquire Award to Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. So then, of course, we played a number together, and that little bit of film turned out to be the only filmed evidence of Charlie Parker playing live.”

Heady stuff, but Parker and Gillespie weren’t the only legends to be caught on film with Dick. As the go-to piano man of New York, Hyman did lots of television work in the ’50s and early ’60s, including the hugely popular Arthur Godfrey Show. From 1959 to 1961, Dick was Godfrey’s musical director, a sort of proto–Doc Severinsen (or Paul Shaffer) whose musical guests included acts like the vocal group The Hi-Lo’s and the brilliant jazz stylist Erroll Garner, with whom Dick played duo pianos. And surely the Columbiana archive could supply shots of Morningside Heights in the mid-1940s, when Hyman arrived on campus: cue Benny Goodman’s “Stompin’ at the Savoy,” accompanied by a montage of fresh-faced college men in single-breasted jackets and straight-legged pants and the occasional Harlem-influenced zoot suit, with a felicitous Hyman voice-over: “In college I was a liberal arts major and did as many music courses as I could within that. There was music history with Paul Lang and composition with Jack Beeson. But as important as anything else were the activities at WKCR, which in those days was called CURC [Columbia University Radio Club].” We see photos of Lang and Beeson, and yearbook shots of the radio station. “I did lots of programs on CURC — a jazz program or two, and then sometimes we had famous jazz guests come on and join us, like Willie ‘The Lion’ Smith.” Insert: a shot of the cigar-chewing stride master Smith playing a Harlem rent party. Hyman: “The radio station was as important as anything else — a place where like-minded people could get together and play. And it wasn’t just jazz — there was musical comedy, original stuff being written by Robert Bernstein and Seth Rubinstein, both fraternity brothers of mine in ZBT. Then I wrote a Varsity Show called Dead to Rights, and I think I also played piano in one — Lou Garisto had composed it."

We then see the hot lights and smoky jazz bars of 1950s New York, to which Hyman would soon graduate — places like Wells Music Bar in Harlem, Café Society in Greenwich Village, and a new club at 52nd Street and Broadway called Birdland (named after Charlie “Yardbird” Parker), where Dick became the house pianist, jamming with the likes of Parker and Lester Young. Hyman: “The advantage of Columbia from my point of view was that it was near Harlem and only a subway ride away from Greenwich Village, where I occasionally sat in at clubs and went to hear all my idols play — that was possible in those days. [Trumpeter] Max Kaminsky had a band at a place called the Pied Piper on Barrow Street, and I remember going there and sitting in. There were two pianists in the place. One of them was James P. Johnson, and the other was Willie ‘The Lion’ Smith. So I got to know Willie at that point and visited him once or twice at his place in Harlem."

It would be a music lover’s movie. Critics and musicians could weigh in on Dick’s place in the jazz cosmos. The Beastie Boys could deconstruct the lyrics of their song “Root Down,” which contains the line “I’m electric like Dick Hyman.” Statelier commentary could be offered by Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton, both of whom hosted performances by Hyman on the White House lawn. (Too bad Bill didn’t join Dick with his saxophone — who else would be able to say he performed with a US president and Charlie Parker?)

There could even be clips from the dozen Woody Allen films for which Dick has served as composer, arranger, conductor, and pianist.

Richard Roven Hyman was born in New York in 1927 and grew up in the suburb of Mount Vernon. As a child, he studied classical piano with his mother’s brother, Anton Rovinsky, a concert pianist noted for having premiered the Charles Ives composition The Celestial Railroad. While learning Bach and Beethoven from his uncle, Dick was also getting an earful of the 78-rpm jazz records brought home by his older brother, Arthur, whom he greatly admired. Through Arthur, Dick encountered the music of Bix Beiderbecke, Louis Armstrong, Teddy Wilson, and others, and by high school he was playing in dance bands throughout Westchester County.

After Dick completed his freshman year at Columbia, his studies were interrupted by the war. In June of 1945 he enlisted in the Army, then transferred into the Navy through the band department. “Once I got into the band department, I was working with much more experienced musicians than I was used to,” he says. “I’d played in a couple of kid bands in New York, playing dances, but the Navy meant business — I had to show up, read music, and be with a bunch of better players than I had run into.

“When the war ended and I returned to school, jazz itself had taken a different direction. We were now into bebop, so from playing swing and Dixieland, we all changed course, and I became that kind of player. All the younger guys had to emulate Charlie Parker, but I never stopped playing the older styles, and paradoxically, that became more my thing later on.”

Back at Columbia, Dick entered an on-air piano competition on the radio station WOV. First prize was 12 free lessons with Teddy Wilson, the great swing-era pianist who a decade earlier had broken the race barrier as a member of the Benny Goodman Trio. Dick won the contest. From Wilson, Dick learned Wilson’s chord substitutions and elegant Tatumesque runs; and in a satisfying twist, would, in a few years, himself become Goodman’s pianist (a live recording on the TCB label, Lausanne 1950, features a nimble, confident 23-year-old Hyman swinging with virtuosic ease in the company of Goodman, trumpeter Roy Eldridge, and tenor saxophonist Zoot Sims).

And so in the company of legends, Dick Hyman continued the business of inventing himself — accumulating styles and developing, to ever more hair-raising degrees, the astonishing technical facility that is central to the Hyman phenomenon.

“I was never one of those concert pianists who practices eight hours a day,” he says, when asked where he got such scary chops. “When you’re working in nightclubs, you’re in such good shape from playing six hours every night that you really don’t need anything else.”

It’s the sort of answer you’d expect from Hyman, who when discussing his extraordinary skills is as factual and pragmatic as a map enthusiast giving directions. Presumably it’s this same sober temperament that has allowed him to work with showbiz personalities far less agreeable than himself: that he “got along fine” with both Arthur Godfrey and Benny Goodman, two men notorious for not getting along with anyone, affirms Hyman’s reputation as a sideman of eminent professionalism; and while many players in those days self-destructed through alcohol and drugs, it’s probably safe to say that Dick Hyman never fell off the bandstand.

As a studio musician in the 1950s and ’60s, Hyman was equally deft and reliable, as evidenced by his seven “Most Valuable Player Awards” from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences, and by the eclectic list of names with whom he recorded: Tony Bennett, Perry Como, Guy Mitchell, Joni James, Marvin Rainwater, Ivory Joe Hunter, LaVern Baker, Ruth Brown, The Playmates, The Wildcats, The Kookie Cats, The Four Freshmen, The Four Sophomores, Mitch Miller, and hundreds more.

And then, in 1968, Hyman donned yet another hat, making a record that was different from any other before it, and that landed him, the following year, on the Billboard Top 40 — without the aid of a piano or organ.

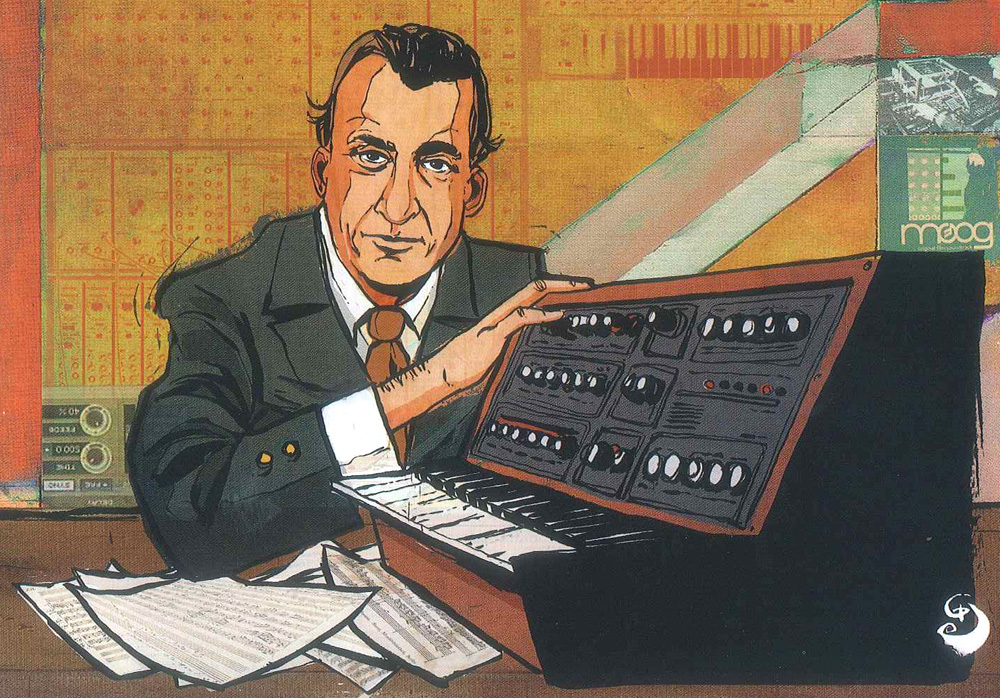

This part of our story bears a particular Columbia stamp. After the enormous success of the 1968 album Switched-On Bach by Walter (now Wendy) Carlos ’65GSAS, which was played entirely on the revolutionary keyboard synthesizer invented by Robert Moog ’57SEAS, Hyman was approached by his record label, Command, about doing his own turn on the early Moog, which Hyman describes as resembling “an old telephone switchboard.” The result was the album Moog: The Electric Eclectics of Dick Hyman. A single, “The Minotaur” — a long modal improvisation over a funky electronic lounge beat — climbed the charts in 1969, finishing at No. 38 for the year, alongside hits by Elvis, Dionne Warwick, Stevie Wonder, and The Who. (A year later, the progressive rock group Emerson Lake & Palmer released an album, Tarkus, featuring Moog noodlings by keyboard superstar Keith Emerson that sounded a lot like Dick’s work on “The Minotaur” — so much so that Dick initiated legal action, although Emerson was in England and couldn’t be summoned to court.)

But Hyman’s success in the exotic new world of electronic music never lured him from his acoustic roots. On June 17, 1973, Hyman played a solo date at The Cookery in Greenwich Village. Those in attendance heard New York’s most dazzling piano player in top form, attacking each tune with breathtaking fluidity and inventiveness, conjuring the spirits not only of Tatum and Jelly Roll Morton, but of Bach, Chopin, and Gottschalk. Yet this thrilling, intimate display of pianistic fireworks would have been lost forever had Dick not brought along a portable tape recorder and placed it atop the piano. Some 30 years later, the “lost” tape was unearthed from Dick’s files and released on CD as An Evening at the Cookery.

All of this, too, could be in our movie about Dick Hyman.

Of course, some would argue that the definitive Dick Hyman movie has, in a sense, already been made.

Woody Allen’s 1983 film Zelig is a faux documentary about the life of one Leonard Zelig, a curiosity of the 1920s and ’30s. Zelig, known as “The Human Chameleon,” possesses a mysterious ability to take on the outward characteristics and mannerisms of those around him, and has a knack for showing up at key historical moments, a background figure blending in anonymously with the famous and powerful. It’s a movie about assimilation and adaptability, alienation and survival, and the power of the mind to transcend physical limitations. The authentic-sounding period music, written and arranged by Hyman (who also penned the witty lyrics to the songs), suggests the composer’s intense identification with the spirit of the times. Of all Woody Allen’s films, Zelig remains Dick’s favorite.

And so the strange case of Dick Hyman ends where it begins. How can one musician be so good, so convincing, in so many styles? Is there, as Woody Allen would have it, a psychological explanation for such a restless, many-sided talent? Is Hyman himself a Zelig-like figure, a musical chameleon who must constantly reinvent himself in order to fit in? Or should we look to an actual documentary, Martin Scorsese’s No Direction Home (2005), in which the subject, Bob Dylan, the multifaceted, spiritually attuned consumer of Americana, describes himself — as one might describe Hyman — as a “musical expeditionary”?

Maybe Dick should offer his own explanation.

“I just began to add styles and become as rounded as I could,” he says simply. “So that thereafter, when I was lucky enough to become a studio player, I was known for versatility.” He adds, without irony: “I guess I still am.”