Before his opera Voodoo premiered at the Palm Garden on West 52nd Street on September 10, 1928, African-American composer Harry Lawrence Freeman received a letter from the dancers in his show. “We your dancing girls,” the note said, “wish you a grand and glorious success.” Despite the dancers’ enthusiasm, the New York Times promptly dismissed Voodoo as a “naïve mélange of varied styles,” and the show was never produced again during Freeman’s lifetime.

You might say that Voodoo was hexed from the start. Freeman wrote the opera in 1914, the year that World War I began. He was forty-five years old and had composed eight operas, starting in 1893 with The Martyr, which was inspired by Richard Wagner.

That it took fourteen years for Freeman to get Voodoo produced was in keeping with the trials of an artist who received many rejection letters throughout his career. The first of several from the Metropolitan Opera came in August of 1935 — almost two decades before a black singer would ever set foot on its stage.

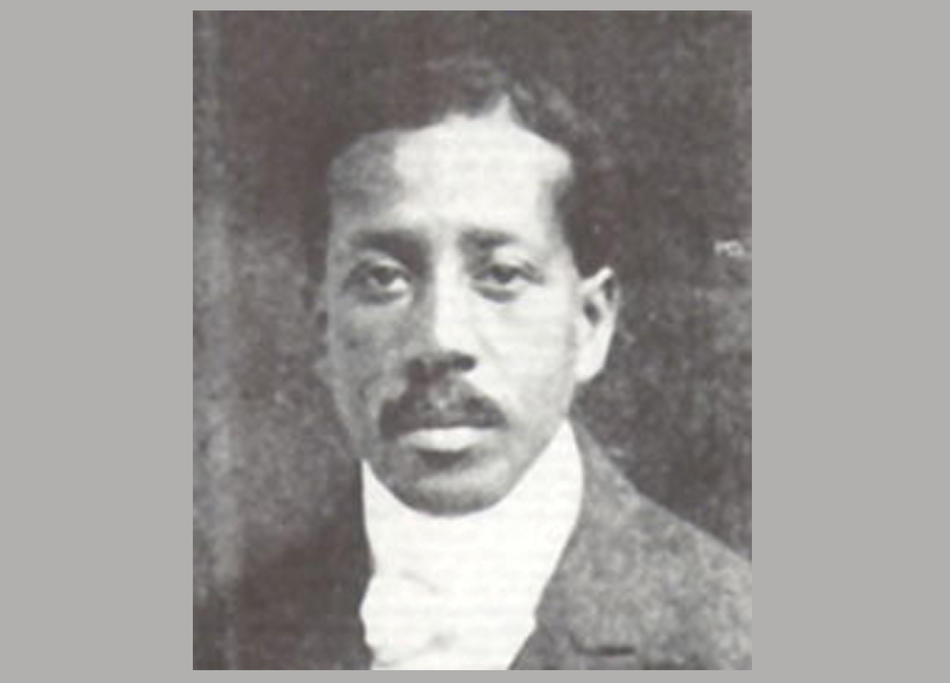

Freeman may not have realized all of his ambitions, but he was a well-known figure in the Harlem Renaissance. By 1920, the “colored Wagner,” as he came to be known, had collaborated with composer Scott Joplin, founded the Negro Grand Opera Company, and opened the Freeman School of Music in Harlem, where he produced some of his own shows. When he died in 1954, he had written more than twenty operas, most of which were unpublished and unrecorded.

But for Freeman’s story, this is more a fermata than a tragic end. In 2007, the Freeman family donated his papers — original scores, family photos, and letters — to Columbia’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library, where they fell into the hands of graduate student Annie Holt ’14GSAS. Now the executive artistic director of the Morningside Opera, Holt, along with the Harlem Opera Theater and the Harlem Chamber Players, was determined to resurrect Freeman’s work.

This summer, the Morningside Opera staged a two-night revival of Voodoo at Columbia’s Miller Theatre. Set on a Louisiana plantation during Reconstruction, the melodramatic tale follows Lolo, a plantation worker turned voodoo priestess, whose love interest, Mando, falls for another woman, Cleota. Strong soprano leads and slow melodies build intensity and anticipation as the love triangle develops.

As he did for most of his operas, Freeman wrote both Voodoo’s music and its libretto. He cleverly combines spirituals and hints of ragtime with more traditional operatic sounds, reflecting both his musical training and his immersion in the culture of his time.

Freeman’s career may have been tumultuous, but his creative drive never wavered, from the moment he first saw Wagner’s Tannhäuser in Denver in 1892, when he was eighteen. He later recalled how the performance changed him:

When I retired that night I could not sleep, as the music was a revelation to me and I was stirred by strange emotions. At five o’clock in the morning, I arose, and seating myself at the piano, composed my first piece. Every day thereafter for two hundred days I composed a new song.