Under heavy iron clouds, in the swish and glug of New York harbor, she sleeps, her dreams of scalloped sea and winking light disrupted now and again by an aquatic squeal that sounds like an orca’s call. Whale song, it’s true, can be heard again in New York waters (humpbacks, fins, big blues), but here at Pier 25, at the foot of North Moore Street, the cry belongs to the 174-foot, 770-ton Lilac as she nuzzles the black rubber fenders wedged between hull and pier. The whales, it seems, could have company in their back-from-the-brink resurgence: if the Lilac’s master realizes a dream of her own, the old ship’s twin engines will fire, her pipes will bang, her pistons will jump, her cranks will turn, and smoke will puff from the yellow stack of America’s last steam-powered lighthouse tender.

Mary Habstritt ’89LS stands at the top of the Lilac’s metal gangway in welcome. She wears jeans, a navy-blue sweatshirt, and wire-frame glasses, and has wind-bleached hair the hue of rock salt and marine rope. “Ships,” she says, leading a visitor aboard, “often have many lives. This was true for the Lilac’s sister ship, the Arbutus, as well. They get reused for different purposes.”

Habstritt ducks through a doorway and into the wardroom, where the officers ate, and where the walls now flaunt photos of the Lilac’s launch in 1933. Habstritt tells of the Lilac’s incarnations: built by the US Lighthouse Service, the federal agency charged with maintaining aids to navigation (it would be subsumed by the Coast Guard in 1939), Lilac, one of thirty-three such vessels produced between 1892 and 1939, spent four decades cruising the busy industrial corridor of the Delaware River, from Wilmington to Philadelphia to Trenton. Her crew of four officers and thirty-four seamen brought supplies and inspectors to lighthouses, made repairs, raised buoys from the water with Lilac’s boom and lowered them onto the deck to be serviced, and, in the days before automated lighthouses, ferried the oil that kept the lights burning. “The lighthouse keeper lived there with his family and basically couldn’t leave, because he had to make sure the light was on all the time,” Habstritt says. “In fact, some of the first females in the Coast Guard were the wives of lighthouse keepers who took over for their husbands.”

Habstritt exits the wardroom into the spring mist, where hull rubs fender in a creaky wail, and walks across the Lilac’s rain-rinsed deck to the engine room. In World War II, she says, Lilac, like all Coast Guard vessels, came under command of the Navy: she was painted gray and armed with depth charges and small guns to protect the coast. “There were concerns about mine-laying U-boats, so she also was fitted with a degaussing system — an anti-mine system that neutralizes the ship’s magnetic field so that magnetic mines won’t attach to the hull. And it’s all still here.” Habstritt laughs. “There’s a huge copper coil running around the hull of the ship, and controls for it up in the pilot house. But,” Habstritt adds, “she had no encounters that we know of.”

After the war, the ship was disarmed, repainted Coast Guard black-and-white, and returned to full-time buoy and lighthouse tending and responding to maritime emergencies like collisions and fires. In 1972, the Lilac, after thirty-nine years of continuous use, was decommissioned. The government donated her to the Seafarers International Union as a stationary training vessel at a seamanship school on the Potomac River. After the union retired her in 1985, she was sold into private hands and berthed at a marina on the James River in Richmond. In 1999, she went on the block again. She could well have ended as scrap, or, like her identical sister, been scuttled, another faded species wiped out.

That’s when the New York–based nonprofit the Tug Pegasus Preservation Project — soon to spawn the Lilac Preservation Project — jumped in. By the winter of 2003, the Lilac was towed north, a ghost ship filled with small wonders: the nooks and cabins, the mess halls and galleys, the hanging cots and the original Webb Perfection stove, the steep ladderlike stairs with their rails wrapped in sailors’ rope work, the living quarters so starkly reflective of military hierarchy, the honeycombed layers of Gumby-green paint (“The sailors call it ‘puke green,’” says Habstritt. “It’s supposed to be calming”), and, down below, the pièce de résistance, which Habstritt now approaches, lowering herself nimbly from the near-vertical stairs. Here, in this dank tomb of pipes and water tanks, lies an engineering triumph whose mechanics Habstritt knows well.

“There’s one engine for each propeller,” she says, standing between the two iron red, twelve-foot-long steel engines. “The steam comes in from the boiler room and enters the engines through these pipes.” The engines have three cylinders on top. “You’re trying to get as much work out of the steam as possible, but it starts to cool as soon as it hits the engine, and so each time the steam is reused, it needs more surface air to do the same amount of work. That’s why the cylinders gradually get bigger, and why it’s called a triple-expansion steam engine.”

A landlubbing Minnesotan, Habstritt had come east to study at the only Ivy League school with a library program. Soon she met a man who belonged to the Society for Industrial Archaeology, and who encouraged her to attend a gathering of the New York chapter. “It opened up a whole world of the history of manufacturing and the stories behind the products we use every day,” Habstritt says. The president of the local chapter was Gerry Weinstein, a steam historian and industrial-landscape photographer.

After she and her boyfriend split up, Habstritt moved to the Twin Cities and took a job at the University of Minnesota library. During that time, she and Weinstein struck up a courtship. They got married in 1997, and Habstritt returned to New York, where she began researching the history of industrial sites and advocating for preservation.

“The more I learned about these places, the more I realized they were disappearing,” says Habstritt. “In the world of preservation, industrial sites are the stepchild. People can understand the value of a historic house where Edgar Allan Poe once lived and worked. But an abandoned factory? Not so much.” She mentions the Domino Sugar factory on the East River, sold to a developer last fall, as a museum-worthy structure (the sugar trade, Caribbean-US relations, monopoly, Teddy Roosevelt, factory life) that we demolish at the peril of national memory. “I felt that a lot of these sites needed someone to help save them,” she says. Powerful forces stood in opposition, naturally, and for Habstritt, fighting those frequently predetermined battles grew disheartening. But a ship was different; a ship wasn’t real estate. Everyone wanted to save a ship.

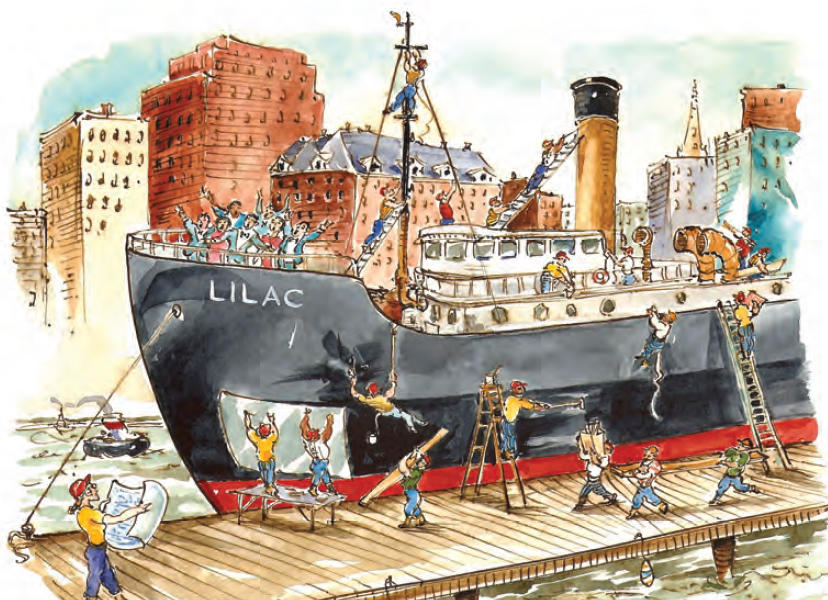

Habstritt took over as the Lilac Preservation Project’s director in 2011, learning all she could about the ship from government records and former crew, and about steam engineering from her husband (“we have a collection of steam engines at our weekend place”). She has been overseeing the ambitious volunteer-driven restoration effort at Pier 25 (painting, wiring, cleaning, refurnishing, patching, plumbing) as well as holding onboard events (readings, art exhibits, lectures, theatrical and choral performances) during the May-to-October season.

Habstritt climbs up into the bridge, the room from which the captain guided the Lilac along the Delaware. Polished binnacle, telegraph, nautical charts, wooden ship’s wheel, radar equipment — all still here. Habstritt, underscoring the many lives of ships, recalls the fate of Lilac’s sister. “The Arbutus worked the Hudson and was based on Staten Island,” she says. “After her decommission, she ended up being used as a workboat for Mel Fisher, the famous treasure hunter. In 1985, Fisher and his crew found the Nuestra Señora de Atocha, a shipwreck from 1622 that yielded a lot of gold. When they were done with the treasure hunt, they sank the Arbutus off the Florida coast. That’s one way to get rid of a ship — scuttle it. So she’s down there off the Florida Keys.”

As for the Lilac, the survivor, the last of her kind, rocking gently on the Hudson, she now enjoys the status of museum ship — a boat that never searched for treasure, but instead became it.