Q: What do you get when you cross a Beat with beetles?

A: Bats.

Now dig: It’s 1959, New York City. Jack Kerouac stands in the middle of a Lower East Side studio in a flannel shirt, arms outstretched. People sit on the floor, on pillows, rapt as disciples. Outside on East 3rd Street, Italian and Ukrainian toughs walk past with cigarette packs in the sleeves of their T-shirts. Down the block, the Hell’s Angels gun their Harleys. And right next door, a sculptor named Oldenburg dreams of giant ice cream cones.

Kerouac mounts the first rung of a stepladder, reaching his crescendo. White muslin behind him, naked bulb above, pictures on the walls. To his right, a young black guy leans against the window jamb, listening. It’s George Preston, sophomore at City College, painter, poet, seeker, baseball lover, collector of art and of people. It’s his pad, his stepladder. The cops were chasing the poets from the park, so Preston, a sociable cat tuned to the higher frequencies, opened his doors. And in they wandered: Corso, Rexroth, Selby, Patchen, Mailer. Ginsberg from 7th Street. Frank O’Hara and Leroi Jones. The mad ones.

Fifty years later, Preston’s door is still open. Only now he lives up on West 162nd Street in upper Harlem, in a latte-colored brownstone that shelters not a generation of American writers, but a teeming menagerie of African art. Hundreds of masks, figures, implements, and other sculptural objects cram the shelves and animate the walls in a controlled profusion that Ginsberg might have appreciated.

“In 2003, I began very consciously to turn this house into a demeure historique, modeled on the Delacroix house in Paris, Hemingway’s house in Cuba, and the Frida Kahlo house in Mexico City,” says Preston, standing in the sunny first-floor parlor amid wooden figures with ringed necks and conical breasts, and tribal masks with the arched brows and almond eyes that inspired Modigliani. “Those are all houses in which there lived active artists who also collected.”

Preston calls it the Museum of Art and Origins (MoAAO), which means that “we make a great effort to show art that has a reasonably straightforward relationship to what generated it.” That might explain why Preston is less interested in the polished, flawless specimens that adorn the mantelpieces of Fifth Avenue (and which are beyond his price range, anyway) than he is in items that bear the patina of their own history as useful, living objects — a context that, for Preston, permits a deeper aesthetic understanding. In that spirit, visitors are free to handle much of the art. “Different objects have different histories and surfaces,” says Preston. “Some sculptural objects benefit from a certain amount of natural contact.”

The museum, with its peaceful, sun-dappled rooms, is one of dozens of local institutions that are fostering what Preston refers to as the “new Harlem Renaissance.” Within two blocks of MoAAO are Jumel Terrace Books, an antiquarian bookshop specializing in Harlem history and culture; jazz pianist Marjorie Eliot’s jam sessions, held every Sunday afternoon in her Edgecombe Avenue home; the old Romanesque Revival house of Paul Robeson ’23LAW, recently bought by pop star and onetime Columbia student Alicia Keys; and, just outside Preston’s window, across the shaded cobblestones of Jumel Terrace, perched on a lush green estate, the Morris-Jumel Mansion (built in 1765), the oldest extant house in Manhattan, and, during the Battle of Harlem Heights, the headquarters of General Washington.

Preston casually drops by these landmarks, where he is greeted with neighborly familiarity, like a small-town sheriff. And people drop in chez Preston, mostly by appointment, where they can receive a personalized tour of the collection, which includes objects produced in regions covered by Ghana, Nigeria, Mali, Guinea-Bissau, Senegal, Central African Republic, Gambia, Sudan, Togo, Gabon, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

“I began collecting seriously in high school, when I began to see the difference in the quality of the work of my fellow students,” says Preston, who attended the High School of Music and Art on West 135th Street. “You begin to make decisions; aesthetics is all about the choices that you make.” He pauses to water a bamboo plant beside an old grand piano covered with feathered headdresses. “I have a mask downstairs, and a lot of people don’t like it,” he states wryly. “They say it’s no good. I happen to think it’s great because everything is wrong with it, but it came out right. And I can understand what the artist was doing — he was a very daring guy.”

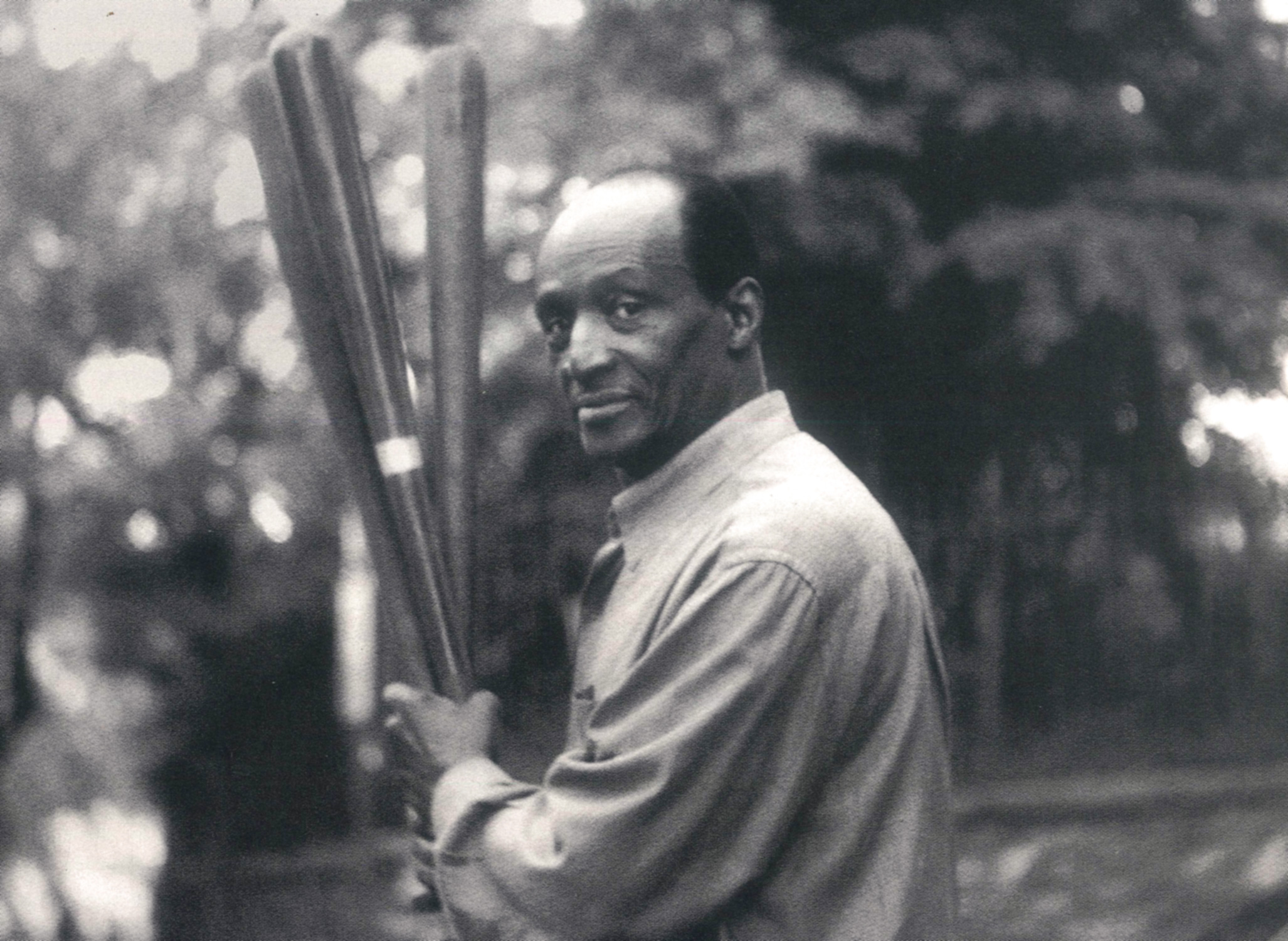

Dressed in track pants, a necklace of red and white beads, and a Yomiuri Giants baseball cap of black and orange, Preston looks like a retired ballplayer who has stayed in top condition. As a kid, when he wasn’t playing stickball, he’d watch his beloved Giants — the New York Giants — from the rocky heights of Coogan’s Bluff, an escarpment that overlooked the massive horseshoe of the Polo Grounds. From that vantage Preston could see a sliver of bright green outfield, and, with a portable radio at his side, would imagine himself out there in the grass, tracking down fly balls.

He finishes tending the bamboo and sets down the watering can. “My collecting in African art has been very meticulous and purposeful,” he says in his measured, deliberate way. “As a result, I sometimes collect objects that might not be the finest aesthetic examples of the genre, but might serve some educational purpose. I try to acquire objects that are highly individual expressions, idiosyncratic examples of a type.”

That’s an apt descriptor of the man. As Columbia’s first African American PhD in art history (he taught the subject at City College for 32 years), Preston has whittled out a snug niche for himself in the city’s cultural life. A recent party at MoAAO, which coincided with a major Sotheby’s auction of African art, drew an eclectic and attractive crowd of dealers, collectors, academics, and artists. Preston moved from floor to floor, room to room, clearly enjoying the mix of people he had brought together. To one charmed, wine-sipping guest, Preston reminisced about the old scene down on East 3rd. “We had no racism, no sexism, no homophobia,” he said. “It wasn’t studied or self-conscious; it was just how we were.” Even his strongest convictions — try getting him started on politics — are smoothed by a deep composure, a serenity that seems to flow from the world of inanimate things. Whether he’s discoursing, say, on the Ghanaian constitution, or the origins of a Chokwe chief’s pipe, or the virtues of Derek Jeter, there remains an essential silence about him, a profound patience, a fluidity, an elusiveness. “Be like sand,” he once said. “Rope maker can’t tie up sand.”

In the mid-1960s, after the Giants left for San Francisco and the Beats gave way to the Beatles, Preston was living downtown on Duane Street, trying to make it as a painter. One day, while scavenging for wood, he decided that what he really needed to do was make money, perhaps in academia. “I thought that if I had a job that sustained me, I’d just make art and not care about becoming a famous artist,” he says. “So I took the 1 train to 116th Street and asked someone where the art history department was. I walked into Schermerhorn between one and two o’clock — which happened to be the one hour of the week when Douglas Fraser had his office hours.”

Fraser, a professor of art history and archaeology, took an interest in Preston, who had just returned from Mexico, where he’d lived for three months with the Mazatec Indians, known for their ritual use of hallucinogenic mushrooms. Preston agreed to show Fraser his journals from the experience.

“A couple of weeks later, I got a letter from the president of the University, welcoming me,” Preston says. “I also received a Title IV grant for the study of non-Western culture or language. Art history was an elite occupation, dominated by people who were, shall we put it politely, not in my class, and there was a lot of doubt about me at that time.” But Preston had his champions, including Fraser and Near East specialist Edith Porada, and in 1968, as the children of Kerouac and Jones crafted their own form of rebellion, Preston, in pursuit of his doctorate, set out for Africa. It would be the first of many journeys.

Ghana was his hub. There, Preston lived in a village with the Akan, the country’s largest ethnic group, renowned for their art, especially their jewelry. The locals grew fond of this interesting American. The feeling was mutual. Ties were formed, trust was built, and Preston, not for lack of opportunity, refrained from exercising at least one of his passions. “One has to be judicious and discreet when collecting or buying something from an area in which you are doing scholarly research,” he says, adding that most of his purchases of African art were made in New York, London, and Copenhagen. In 2001, the Akan, in a show of respect and admiration, bestowed the foreigner with an exalted honor.

“At four in the morning, I was hidden, and the whole town scoured the village looking for me,” says Preston, describing the ceremony. “When I was located, two men appeared, with guns pointed. The first thing they did was put a bundle of twigs in my mouth, so that nothing should come into me or out of me.” Preston was carried aloft through the village. Hours later, the twigs were removed, and Preston, in plain shirt and pants, was set on a stool. A goat was slaughtered and its blood was poured onto Preston’s feet. The blood trickled between his toes and into the ground, sealing him with the ancestors. When he danced, he could say: I am of this earth.

With that, Preston had become a tribal chief of the Akan people. A de facto judge.

“In a certain sense, you are a slave, a public servant,” says Preston, explaining the symbolism of the arrest, the juxtaposition of authority and abasement. “Akan iconography is very much one of constraint.”

In subsequent travels to Ghana, Preston has settled a few minor disputes with the same prudent eye that he brings to his collecting. And though he generally adheres to the principle of not bringing home any carved wooden objects from his Ghanaian visits — one must be discreet — he did end up making a small exception.

Which is where the beetles come in.

Preston, baseball lover, had noticed over the past few years a disturbing trend in the Major Leagues. Bats were shattering left and right, sending jagged missiles into the stands, the dugouts, up the baselines, at the pitcher’s head. It all started in 2001, when San Francisco Giants outfielder Barry Bonds crushed 73 homers while using (among other things) a bat made of maple instead of the standard ash. Maple is harder and tends to explode rather than crack. Bonds’s staggering success led to an increase in maple bats in the Majors, a trend that has since accelerated thanks to the handiwork of a wood-munching beetle called the emerald ash borer, thought to have hitched to the U.S. from Asia 15 years ago in a packing crate. Ash forests from Michigan to Maryland have been devastated,causing maple bats to flourish and shards to fly, and igniting a space race among homespun inventors for the ultimate shatterproof wooden bat.

Preston’s solution can be found in his basement workshop: a cache of some 50 cherry-hued baseball bats, made from a tree that Preston had scouted in West Africa, and whose name, at this delicate juncture in the marketing process, he prefers not to reveal. The bats, manufactured in Ghana to Preston’s specifications, have shown promise in trials conducted by Preston himself, against live pitching.

That’s right: Preston, at 71, plays baseball — right field, second base — in an over-40 fast-pitch league. With him, the discernment required of both the connoisseur and the tribal chief might help to crack a cosmic mystery that even the poets can’t touch.

“People ask me, how do you hit the ball?” says Preston, who last season batted an eerie .320. “It’s about two-fifths of a second from the time the ball leaves the pitcher’s hand, so you’re certainly not standing there thinking. Rather, you’re making a reaction, a guess, but that guess is based on a tremendous amount of information.” Preston lifts a bat from the woodpile, grips the handle, flexes his wrists so that the barrel cuts a tight circle in the air. “The difference between collecting and baseball is that once you make that swing, you’re committed. In collecting, I can still stand back and think.”