Most Americans are aware of the urban rebellions of the 1960s that exploded in places like Harlem, Newark, Watts, and Detroit. Such uprisings are widely assumed to have peaked in the days and weeks following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in April 1968. In America on Fire: The Untold History of Police Violence and Black Rebellion Since the 1960s, Elizabeth Hinton ’13GSAS corrects this misconception. A professor of history and African-American studies at Yale, Hinton not only documents the rebellions that continued to proliferate with astonishing frequency and bloodshed between 1968 and 1972 — often in smaller cities that flew beneath the radar of the national media — but also reveals how fundamental this forgotten “crucible period of rebellion” was in defining “freedom struggles, state repression, and violence in Black urban America down into our own time.”

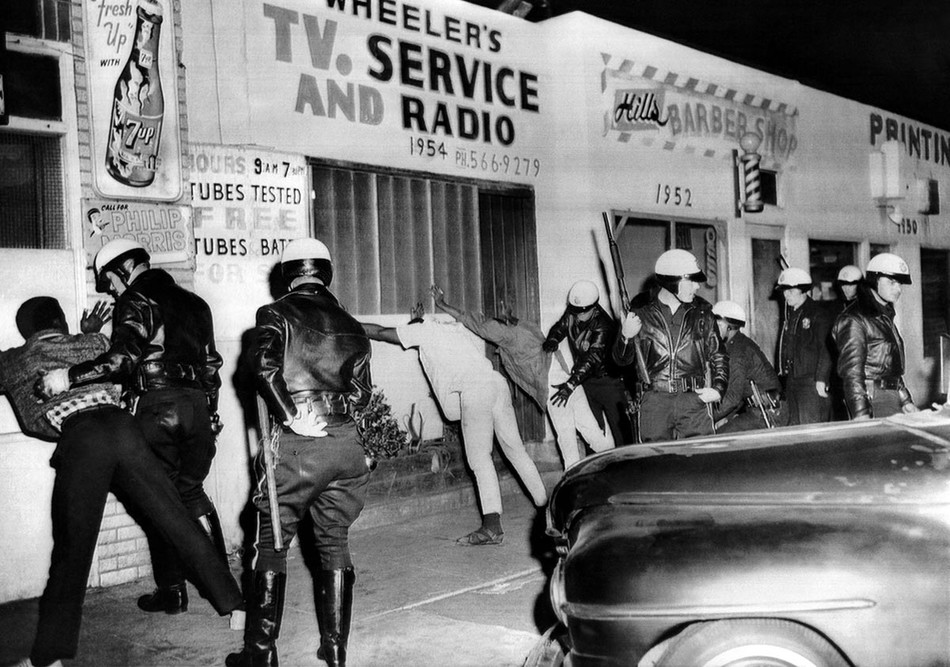

Hinton persuasively argues that these rebellions — 1,949 of them in three and a half years, resulting in forty thousand arrests, twenty thousand injuries, and at least 220 deaths — were nearly always precipitated by an unwarranted act of police overreach against Black people who were simply pursuing their everyday lives or committing minor infractions (violating a park curfew, for instance). Victims’ responses would be met with outsize force from the police (often aided by white townspeople), and a rebellion would escalate from there in a vicious, all-too-predictable cycle of violence that could sometimes persist for years.

Hinton’s analysis of how police forces across the nation evolved into de facto armies is both fascinating and deeply demoralizing, since, among other things, it underscores the tragic consequences of wrong-headed public policy. To summarize broadly: For a heady moment in the early 1960s, it looked as if the US might finally be ushering in a “Second Reconstruction,” thanks to the civil-rights movement’s success in promoting the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. This dream collapsed as President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty morphed into 1965’s War on Crime and culminated in the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968. This law’s provisions ran counter to nearly all the recommendations of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (popularly known as the Kerner Commission, after its chair, Illinois governor Otto Kerner), which a crime-obsessed President Johnson convened in the aftermath of 1967’s “long, hot summer” of Black rebellions. The commission’s report, issued in February 1968, concluded that the source of this discontent was entrenched poverty, inequality, and racism (within law enforcement as well as the wider society) and recommended huge infusions of federal money not into more policing but into social programs to create jobs, improve schools, and provide access to decent housing and health care for underserved minorities. Call it the beta version of “defund the police.”

The Safe Streets Act, passed three months later and two months after Dr. King’s death, managed to ignore nearly all these recommendations and instead inserted the federal government into state and local law enforcement for the first time in history. The act pumped money into police departments in cities large and small across America and armed them with military-level ordnance diverted from the vast surplus of weaponry being produced for the Vietnam War. (Among these weapons of war was tear gas, a diabolical and heretofore rarely used chemical agent deployed in Vietnam and immediately embraced by law enforcement at home as a supposedly non-brutal way to subdue unruly crowds.) From 1964 to 1970, annual federal funding of state and local police mushroomed from zero to $300 million. Armed to the hilt, police forces across the country proceeded to act accordingly.

Now here we are, half a century later. (Say their names: George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Daunte Wright …) Yet Hinton’s book, while undeniably grim, is not despairing. She offers no prescriptions, but she hints that some possible remedies for the blatant abuses and inequities highlighted by today’s Black Lives Matter movement may have been hiding in plain sight since 1968, in the Kerner Report. (Not for nothing did Dr. King call it “a physician’s warning of approaching death, with a prescription for life.”) Perhaps a small first step might be to get a copy of that book, newly available in a revised version edited by Columbia journalism professor Jelani Cobb, into the hands of all 535 members of the 117th Congress. Only when, as Hinton writes in the final pages of America on Fire, “the forces of inequality are finally abolished and the nation no longer empowers police officers to manage the material consequences” of this inequality can the long-awaited “Third Reconstruction” envisioned by many contemporary Black leaders have any chance of arriving.