On a gray, humid Monday in early June, half a dozen young men gather at a seawall along the Potomac River in Alexandria, Virginia. They wear baggy jeans and oversized T-shirts and, somewhat awkwardly, life vests of bright yellow and red. Standing around, they fiddle self-consciously with the straps of their vests or squint up at the fast-moving clouds. Some words fly out, a call and reply, but the banter falls flat, not loose and natural like it wants to be. Laughter rings, fades, and is replaced by the roar of a low-flying passenger jet as it prepares to land at Reagan National Airport upriver. One of the young men steps away to nurse his anxiety in private.

Maybe it’s the water. The basic fears. More likely, it’s the solemn, unassuming object resting on the ground a few feet away: a plain wooden boat, 12 feet long, similar in shape to a canoe. With its smooth curves and cunning points it resembles a long blue-gray fish, and even while idle it seems to possess an obscure intelligence. The young men are especially sensitive to the spirit of this boat, since they’re the ones who built it. But it’s a spirit they don’t yet know; the boat could roll, capsize, betray a workshop error that someone thought he could hide. Or maybe it’ll just sink from the get-go.

Consciously or not, the builders keep themselves at a discreet distance from the thing they created. No one even looks at it.

Two men in their 50s then appear on either side of the boat, and together they lift it off the ground. The younger men turn to watch, pokerfaced, as the elders, without ceremony, lower the craft into the tea-colored water. With barely a splash, the boat enters its element for the first time. And floats. That’s a start. But will it work? Will it move with grace? Will the laws of hydrodynamics bear out the penciled measurements, the solved fractions, the calculation of angles?

Three of the young men step down off the seawall and into the craft, one at a time. The first two sit down on the wooden seats, but the third, a heavyset kid named Mike, gets in tentatively, and the boat begins to rock. Mike tries to adjust, knees bent, hands flat on the air like a frozen dance move.

“Down!” comes a laughing voice from onshore. It belongs to Joe Youcha ’84CC. “Get your big butt in the bottom of the boat!”

Mike laughs, too, and manages to get down without causing any maritime mishaps. “I don’t wanna get no seaweed on me, man,” he says, grabbing the oars. Then, with abrupt authority: “Let’s go.” Oars working, Mike moves the boat away from the wall. The three boaters are serious now, testing things out, feeling the weight of wood and water, the motion and response. Thirty yards out, they begin to relax, and now their true, free laughter can be heard ashore. Their boat is good, and they know it; it glides at the calm clip of a patient shark. They could take this baby clean across the river if they wanted, to the Maryland side, green with trees.

Alexandria, Virginia, wasn’t named for the city in Egypt founded by Alexander the Great, but the coincidence seems fitting. The prosperous Hellenistic city, once a leading center of learning, is now Egypt’s largest seaport, while the prosperous town on the Potomac, where nearly half the houses and condos are valued at more than $500,000, once boasted a busy port of its own, clogged with cargo ships bringing Antiguan rum, Portuguese wine, sugar from New Orleans. And today, Alexandria is home to an innovative learning center that those early boatbuilders, the Egyptians, might have appreciated: the Alexandria Seaport Foundation (ASF).

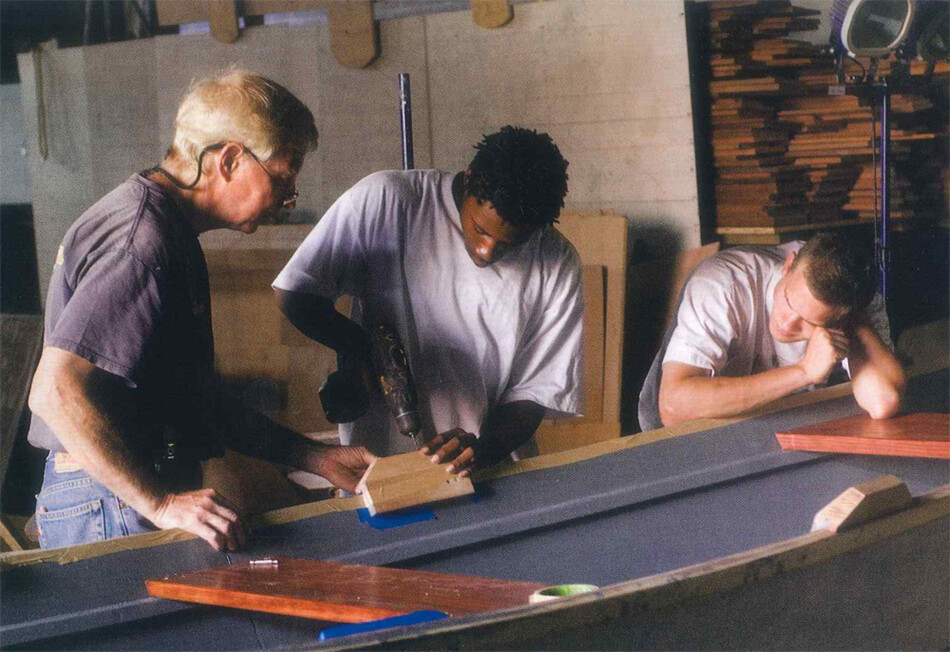

Executive Director Joe Youcha is the guiding force behind the ASF, which began in 1982 with a mission to preserve the city’s maritime heritage. Youcha came aboard in 1992 — literally aboard, as the foundation’s offices are located in a floating boathouse — and launched a community boat-building program aimed at giving at-risk youths a chance to take charge of their lives. Within a five-mile radius of Old Town Alexandria, where well-heeled government contractors live on quaint historic streets once traversed by George Washington, there are hundreds of kids who won’t make it to the 12th grade. That leaves no shortage of candidates for the ASF’s intensive four-month program, which falls somewhere between boot camp and boat camp: The apprentices, most of whom have left school or had scrapes with the law, spend half the day constructing wooden boats and the other half being tutored in math, history, reading, and writing. All of this occurs in a vast riverfront warehouse owned by the Washington Post Company, which took an interest in the boat-building program and provides use of a section of its facility rent-free. The donated space contains a large workshop permeated with the spicy essence of fresh sawdust (Port Orford cedar, African mahogany: Youcha speaks of wood with a sommelier’s discernment) where young apprentices can be seen working on the elaborately ribbed skeleton of a boat-to-be, starkly illumined by an overhead fluorescent lamp. Dozens of tools hang on the wall, and the floor is crowded with piles of donated lumber and pieces of heavy machinery: band saws, table saws, joiners, drill presses. In the classroom area, housed in an adjoining building, educator Darius Ligon teaches kids history through concepts relevant to their lives as carpenters-in-training: the history of tools, the history of labor and unions, the history of cathedrals and how they were built. Articles from the Washington Post are used for reading and comprehension. And all the math — arithmetic, fractions, decimals, geometry, basic algebra, introductory trigonometry — is directly applied in the workshop: hands-on learning in the truest sense.

But this isn’t school; it’s a job. Apprentices are paid $6.50 per hour to work and learn, though with incentives the rate can climb as high as $11. There are, of course, strict rules to be followed, and Youcha, a friendly, hard-nosed guy in a polo shirt and a baseball cap, lays down the law to each new arrival: You must be at the workshop each morning by 7:30. You’re late, you work at minimum wage that day. Miss a day, you’re docked two days. Three violations within a two-week pay period, and you’re fired. But if you complete the program — which includes earning a General Educational Development (GED) diploma — you get direct entry into the United Brotherhood of Carpenters. (Union membership requires tools and a car, and if an apprentice is in need, the ASF helps out with that, too.) From there, many things become possible: good money, a sense of purpose and direction, improved self-esteem, and the chance to build a lifelong career.

Since the boat-building program’s inception in 1993, the success rate for the apprentices has steadily increased, with success defined as an individual being on a career path or in school a year after graduating. Last year saw an overall 80 percent graduation rate: 24 apprentices moved into the workforce. Given the difficult circumstances facing most of the kids, including, often, the simple problem of transportation, the rate of success is impressive. Still, it hurts when a kid drops out, and Youcha doesn’t give up easily. Second chances have been offered; doors remain open.

“The kids we work with break down into a few different groups,” Youcha explains. “First you have the immigrants, generally from Central America, who are really no different from the Italian kids [community organizer] Saul Alinsky was dealing with in Chicago in the 1930s. In the majority of cases, the parents of these kids are working their asses off, but though the parents are here physically, mentally they’re still in the Old Country. The kids feel they belong neither here nor there. And so they find their place in gangs.

“Some kids come out of Alexandria’s traditionally poor populations — third- and fourth-generation welfare recipients, both African American and white. Then we have kids who don’t have trouble with the law, but are just wired differently — kids who are so learning disabled they’ve been classified as emotionally disturbed.”

The last group Youcha identifies is refugees from war-torn countries. Among the current class of apprentices, one, Mohammed, was a child soldier in Sudan.

The ASF takes kids who are referred by the courts, police, or schools, but it is not part of the court system. “We will not be a condition of parole and probation,” says Youcha. “Because what’s absolutely critical is having the kids be motivated learners and motivated participants in the program.”

Also critical is the dedication of the volunteers who contribute more than 8,000 hours a year and come from as far as 60 miles away. These older, retired men, white-haired and sun-weathered, range from a former executive at AT&T who grew up on the water in Severn, Maryland, to a U.S. Army Special Forces veteran of Vietnam and erstwhile professional soldier whose quiet, serious manner in the workshop serves as a persuasive model, if not a vaguely intimidating one. Youcha describes the volunteers as “overachieving white males who have always wanted to build boats, or grew up building them.” He believes that apprentices can benefit simply by working alongside these experienced and accomplished men. The program is about socialization as much as anything else, and in a workplace culture where, as Youcha says, “bullshit isn’t tolerated,” discipline problems are extremely rare.

Youcha credits the rich pool of volunteers in part to the proximity to the nation’s capital. “For years, the government brought our best and brightest to this area from all over the country,” he says. “It’s the draw of the boats that brings them to us. They come because of the boats, but they stay because of the kids.” A strong military influence can also be felt throughout the program. Up until a few years ago, before the ASF focused on sending kids into the building trades, the military was seen as a good option in some cases, and several of Youcha’s kids were shipped to Iraq. One of them was killed. (As of 2004, the ASF no longer refers graduates to the military.) More fortunate was Steve Hernandez, a 1999 graduate who spent the next five years in the Marine Corps, where he became a helicopter crew chief before returning to Alexandria to raise a family. Now Hernandez is a paid instructor in the program, one of only six full-time staff members. And that’s how Youcha likes it: He encourages people to stay in touch, or, as in Hernandez’s case, to come work for him.

“Joe’s a great guy,” says A. J., a recent graduate who was born in Ethiopia. “He’s the one who pushed me to finish my education. He’s always there for you; he’s amazing. Not a lot of bosses would do that.” A. J. now has a well-paying union job remodeling the roof of the Pentagon, a job Youcha helped him get. He’s also studying mechanical engineering at a nearby community college and plans to transfer to George Mason University in the fall.

As a kid growing up on the Hudson River in Rockland County, New York, Joe Youcha got his feet wet early in the boating world. When Joe was five, his father, Isaac “Zeke” Youcha ’53SW, brought home a sailboat that had been made by a friend who worked at a boatyard in Nyack. “By the time I was six,” Joe says, “I was fixing it.” Zeke had all sorts of tools, and he taught his son how to use them. The spiritual aspect of carpentry as posited by some theologians notwithstanding, the younger Youcha was hooked. Here was a great secret revealed, the key to working cooperatively with nature. “Sailing is just a wonderful experience where you’re using everything that you’ve got in order to be able to trick the wind to let you go from point A to point B,” Youcha says. “That’s always been a fascinating equation for me.”

During high school, Youcha worked on boats on the Long Island Sound, then went to the University of Michigan to become a naval architect. When he realized that he wasn’t cut out to be an engineer, he transferred to Columbia as a history major. There, he joined the fencing team, and later, in the reading room of Butler Library, met Jessica Kaplan ’85BC, whom he later married. After graduating, Joe and Jessica moved to Philadelphia, then to Arlington, Virginia, and then to Colorado, where Joe got a job working with computers. But all the time he was thinking about boats; his dream was to start a community boat-building program for families and kids like the one founded by John Gardner ’32CC at Mystic Seaport in Connecticut. And so when Jessica decided to enter a master’s program in library science and history at the University of Maryland, Youcha saw his chance: With close access to the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries, he began identifying potential communities where he could execute his plan.

The Alexandria Seaport Foundation was a logical place to start since Youcha knew one of the board members, Bill Hunley, through a friend. One day in 1992, Youcha and Hunley met at a local fish joint to discuss Youcha’s ideas. But Hunley had an idea, too. He wanted to extend the pleasures and benefits of boatbuilding to kids in the area who needed help: dropouts, thieves, gang members. Youcha hadn’t been thinking about at-risk kids, but having grown up with a dad who once ran a crisis center in the South Bronx, something about the idea clicked with him. Using the back of a placemat, he and Hunley proceeded to lay out a one-year plan. Now all they needed was money. It happened that Jessica had grown up across the street from Elliot Cafritz ’82CC, whose family had started the Cafritz Foundation, a large grant-making charity in Washington, D.C. Through Elliot, Youcha got an interview with the Cafritz Foundation’s executive director, Anne Allen.

“Anne is this very sensible woman,” Youcha says. “She listened to my pitch, then looked at me and said: ‘How’s your mother with this? How’s your wife with this?’ And I realized afterward that what she was really saying was, ‘All right. You’re just short of 30, you’re an Ivy League grad, and you want to go out and help the world. Well that’s just lovely. But if the women in your life aren’t going to support you, it’s not going to last more than a year.’”

Fifteen years later, the women in Youcha’s life are still onboard, and the quest for funding continues. The ASF receives about half of its operating budget ($720,000 in fiscal year 2007) from foundations and government grants, over a third from private donations, and less than a fifth from government contracts and program revenue generated by sales of boat kits and other commissions. It costs about $11,500 to put one apprentice through the four-month program.

The boat drifts back to the seawall, lands with a soft thump. Mike and his two partners alight, smiling, cracking jokes. The boat is pulled from the water and lowered onto a hand-pulled trailer. The apprentices wheel the boat to the warehouse several blocks downriver, while Youcha, Darius Ligon, Steve Hernandez, and Howell Crim, director of the apprentice program, head across the street to an old bar called Chadwick’s and sit at their customary table at the front. Over beers and sandwiches, the four men have their usual confab about the apprentices, past and present — who’s having problems, who dropped by to say hello, who needs a car, who just got a job, who needs a job. Each kid is like an equation to be figured out; each is important.

At a little after five, Youcha brings the meeting to an end.

Outside, the clouds are parting, and the river takes on an amber blush. The apprentices have since hopped on their bikes, boarded their buses. The waterfront is quiet now.

Joe Youcha walks along North Union Street, through Old Town Alexandria. From here, he’ll drive home to Arlington, where he lives with Jessica and their two young children. As he reaches his car, an ’84 Mercedes-Benz filled with tools and papers, he recalls the words of a Hawaiian canoe builder who had been in town for the opening of the National Museum of the American Indian in 2004. The builder later stopped by the ASF, where he gave a demonstration in Hawaiian boat-building techniques.

“You’ve heard of ‘The Big Kahuna?’” Youcha says. “The Kahuna was the canoe builder. They were pretty much on par with the priests, and the canoe was a central part of their religion. So I watched this guy as he carved out a canoe with these nasty tools, doing this heavy, dangerous work. I said, ‘So how many accidents do you have?’ And he said, ‘We really don’t have very many accidents.’ And I said, ‘Why is that?’ And he looked at me and said, ‘Because every time you make a cut, you have to ask permission of the log.’

“So for me, that’s the real appeal of boat-building: You’re creating something beautiful that in many ways is alive.” Youcha pauses, then adds: “I know it sounds corny, but it’s true.”