B. Stuyvesant Champagne

Bringing bubbly to Brooklyn

Marvina Robinson ’05GSAS has long appreciated a good champagne. As a college student, she remembers evenings sipping fine French bubbly on brownstone stoops in her home neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. “My friends and I would pool our money together for a bottle of Moët & Chandon and drink it out of plastic cups,” she says. “I’ve always loved champagne, and once I got older, I started to dig in a little bit deeper.” So much deeper that today Robinson is the founder and CEO of her own label, B. Stuyvesant Champagne, which is produced in France and sold in the United States.

Robinson, who has a master’s degree in statistics from Columbia, got to know champagne’s complexities while working in the finance industry. “I used to send bottles to clients as gifts, which involved researching brands and learning about the tasting notes,” she says. In 2018, Robinson quit her job at a large bank to realize her dream of starting a champagne brand and bar in Brooklyn. “There are so many beautiful champagnes that don’t make it to the States,” she says. “I wanted to be the person who introduced other champagne lovers to this world.”

The pandemic made opening a bar infeasible, so Robinson began focusing exclusively on her private label. B. Stuyvesant partners with a vineyard in the Champagne region of France to grow its grapes — chardonnay, pinot noir, and pinot meunier — and produce the wine, which is sold online and to stores, bars, and restaurants in and outside of New York City. Robinson, who runs her business and operates a tasting room out of a two-thousand-square-foot space in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, makes regular visits to the vineyard. “I’m not just someone who’s set up abroad,” she says. “I’m very hands-on.”

At B. Stuyvesant’s tasting room, visitors can try the brand’s signature cuvées, or blends, including the best-selling réserve (flowery with spice) and brut rosé (notes of raspberry and red currant), as well as the popular blanc de blancs, consisting entirely of chardonnay. A 750-milliliter bottle of B. Stuyvesant champagne costs around sixty to seventy dollars. “Champagne requires a labor-intensive technique to produce, which is why it demands a high price,” explains Robinson, who also sells her wine in half bottles.

When sampling a champagne, Robinson advises customers to consider the grape composition and the level of dryness. “I always start by smelling the glass before taking it all in,” she explains. “Everyone’s palate is a little bit different, but some of the tasting notes I look for are: Is it toasty or briochy? Floral or fruity? Tart? Crisp? Is the texture velvety as you swirl in your mouth? You start on your front palate and finish on your back palate, so whatever you’re tasting first might not be your finish.”

As one of the few African-American women to own a champagne label, Robinson stands out in the industry. “People are intrigued that I’m not from France and I’m producing champagne,” she says. “But I never lead with my genetics, because I feel they’re irrelevant. I lead with a quality product. Where I’m from is secondary.” Still, Robinson’s Brooklyn roots are very much a part of her brand. “Bed-Stuy is where I was born and raised and still live, and it’s shaped me into who I am today. With B. Stuyvesant I’m paying homage to my neighborhood.”

Gotham Project

Selling the benefits of wine on tap

Until recently, the idea of wine on tap, served like draft beer, was anathema to the serious oenophile. Though keg wines have existed for decades, they have been slow to catch on with the American public or the hospitality industry. Gotham Project, a wholesale winemaking and distribution company run by two veteran vintners, has set out to make wine on tap not only respectable but preferable. “From a taste and freshness perspective, there’s no better way to serve wine by the glass,” argues Bruce Schneider ’99BUS, Gotham Project’s cofounder and managing partner.

Schneider explains that bottled wine, once opened and exposed to oxygen, quickly degrades in quality and begins to spoil. This forces many restaurateurs who sell glasses of wine to discard leftover half-full bottles. Schneider says Gotham Project’s refillable, stainless-steel kegerators keep their contents fresh between pours and regulate temperature. “A big problem with red wine is that it’s usually served at room temperature, which is a little too warm,” he adds.

The kegs, which hold the equivalent of twenty-six bottles, are also environmentally sustainable. “A tap is the only way to serve wine with zero packaging waste — no bottles, labels, corks, capsules, or cardboard boxes,” says Schneider. Since launching in 2010, the company claims to have saved approximately six million glass bottles and more than seven million pounds of single-use-packaging waste.

Schneider, who is also a consulting vintner at Onabay Vineyards on the North Fork of Long Island, comes from a multigenerational wine family. His grandfather was a bootlegger during Prohibition, and his parents ran an importing and distribution company in New Jersey.

In 1994, he started his own winemaking business, Schneider Vineyards, with his wife, Christiane Baker ’91BC, ’16TC. (His advice for aspiring vintners: “Start with good grapes — you can purchase them from reputable vineyards.”) In 1997, Schneider enrolled at Columbia Business School to learn how to build his enterprise. The decision paid off. A grant from the Eugene Lang Entrepreneurial Initiative Fund, which supports MBA student ventures, enabled the couple to buy an old potato farm on the North Fork and start growing their own vines.

The Schneiders specialized in cabernet franc, a parent grape of the better-known, more tannin-heavy cabernet sauvignon. “Cabernet franc has a ton of personality,” says Schneider, who sold his vintages at high-end restaurants and raised the grape’s profile among area sommeliers. “I think of it as the original cabernet. You get beautiful red-fruit characteristics — raspberries, red currants, a bit of strawberry — and a naturally occurring, savory herb quality.” Plus, the grapes are well suited to New York’s colder climate. “It’s a thick-skin variety; it’s winter-hardy.”

After selling the vineyard in 2007, Schneider moved into distribution and, in 2010, teamed up with his industry friend Charles Bieler, a winemaker specializing in rosé from Provence and Washington State, to cofound Gotham Project. The company’s products, including bottles and canned wines, can today be found in more than a thousand restaurants, bars, venues, and stores in New York and across the US. Headquartered in Bayonne, New Jersey, the company sources wine from the West Coast and globally, while also producing its own cabernet franc and riesling in the wine-rich Finger Lakes. “The glacier lakes there are super deep, which makes them very good at retaining heat and moderating the climate,” says Schneider.

Whether up in the Finger Lakes or out on the North Fork, Schneider is a passionate champion of New York wine. “Until the late 1950s and early ’60s, most of what was grown in the state was indigenous varieties like Concord grapes, which make sweet wines,” he says. “That all changed when European varieties like chardonnay, cabernet franc, and riesling were introduced. Now the state is one of the top five producers of wine in the country.”

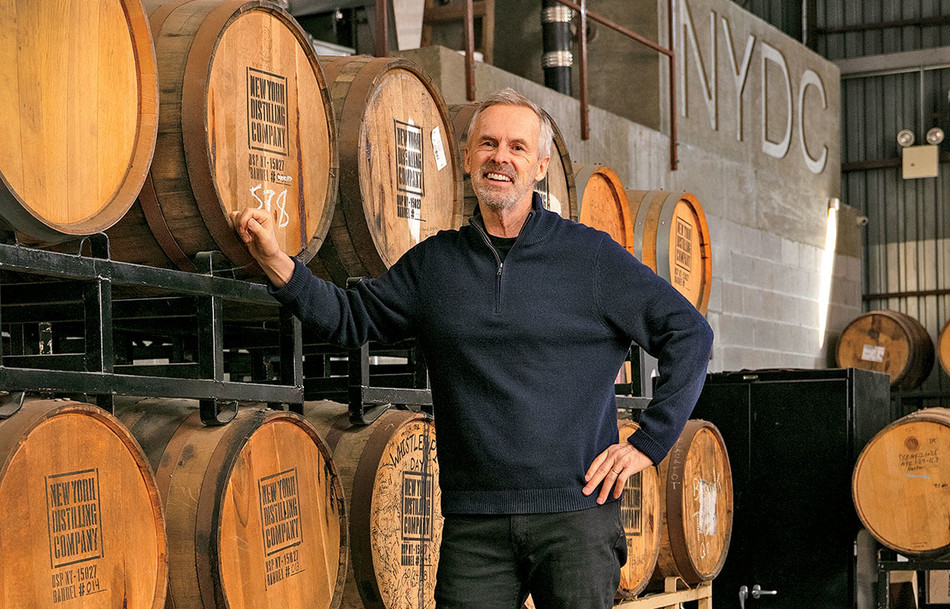

New York Distilling Company

Rediscovering New York rye and gin

Long before Prohibition and the rise of large beverage conglomerates, New York City was among the distilling capitals of the world. “The city has made gin since its earliest days as a Dutch colony,” says Tom Potter ’83BUS, the cofounder and CEO of the New York Distilling Company, a Brooklyn-based maker of artisan liquor. Rye, unlike other types of whiskey, has a rich history in the region, he explains. “It’s what we made here in New York.”

Potter, who has an MBA from Columbia Business School, is tapping into the historic spirit of New York distilling and helping to revitalize a bygone industry. With a focus on rye whiskey and gin, the New York Distilling Company’s creations can be found in bars, restaurants, and liquor stores throughout the Northeast. The distillery and accompanying cocktail bar, the Shanty, have operated out of Brooklyn’s Williamsburg neighborhood since 2011 and will relocate to nearby Bushwick this year.

Potter, who started his career in banking, is a veteran of the alcohol business. In 1988 he cofounded Brooklyn Brewery — an early pioneer in the craft-beer industry — and oversaw the company’s rise as a global brand. He left the brewery in 2004 and entered the wine world, serving as executive director of the American Institute of Wine and Food and planning to start his own vineyard. He opted instead for craft distilling (a less crowded market than wine) and teamed up with his son, Bill Potter, who worked in the fine-dining industry, and Allen Katz, a spirits expert, to cofound the New York Distilling Company.

“We began making gin and rye whiskey, two products which at the time were unusual choices,” says Potter. “The entire gin market was made up of generic, big-company names. Good products, but not craft.” Rye, which is made from at least 51 percent rye grain, had long ago fallen into obscurity as bourbon, which uses corn as its primary ingredient, emerged as the dominant American whiskey during the twentieth century. “Rye is the whiskey that George Washington drank,” says Potter. “It’s the spirit in almost all of the classic whiskey cocktails — a Manhattan, an old-fashioned, a Sazerac.”

The New York Distilling Company, which grows its own rye grain in the Finger Lakes, produces distinctive whiskies including Ragtime Rye, which comes in three varieties, and Mister Katz’s rock and rye, made with rock-candy sugar, sour cherries, cinnamon, and citrus. Good whiskey, explains Potter, comes down to the quality of the grains and the consistency of the distilling process. “The terroir makes a difference. Heirloom crops have higher concentrations of flavor.”

Gin, which is made from vodka or another base liquor, gets its flavor profile from botanicals. “Along with juniper, we use orange and lemon peel and coriander,” says Potter. The distillery’s gins include the Dorothy Parker, which also comes in a rose-infused variety, and, for the stiffest of drinks, the Perry’s Tot, with a hefty alcohol content of 57 percent. “A great gin should taste good in a martini or negroni but still be distinct from other gins,” says Potter. And while he recognizes that gin is not for everyone (“Maybe you had a bad incident in college”), Potter recommends fostering an appreciation for it by drinking a classic cocktail, like a martini. “You’re going to taste the gin. It’s not going to be covered up.”

Having helped lead the craft-beer boom of the 1990s, Potter is amazed by the similar explosion of innovation in liquor and cocktails in the past two decades. “There’s more appreciation now for history and handmade things,” he says. “I think New York State will become a leading producer of craft spirits. We’ve got wonderful distilleries that are growing up and coming to maturity here.”

Enlightenment Wines

Making mead mainstream

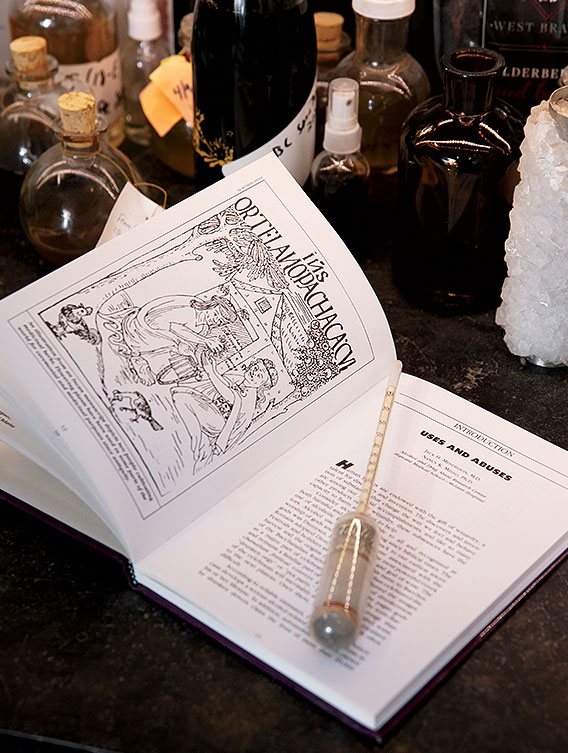

Long associated with ye olde taverns and Renaissance fairs, mead, a wine made from fermented honey, is a libation as old as the Stone Age. The earliest archaeological records of its consumption, found in China, date back to at least 7000 BC. “Mead is by far the oldest alcohol we have evidence for,” says Raphael Lyon ’13SOA, the cofounder of Enlightenment Wines, an artisanal mead maker in Brooklyn. “Today it’s one of the fastest-growing areas of the US alcoholic-beverage industry.”

Lyon, a visual artist and musician, grew up in an “artist and herbalist” household and was a longtime grower and gatherer before taking up mead-making. “I spent a lot of time picking wild plants and learning about the natural ecosystem in my area of the Hudson Valley,” he says. After being introduced to some cider makers, Lyon started creating alcohol “from things I could get my hands on.” By 2009, he had received a New York State winery license and was making and selling his own mead.

Soon after, Lyon moved to the city and began an MFA in sculpture at Columbia’s School of the Arts. After graduating, he connected with business investor Tony Rock ’89BUS. “I thought Raphael’s wines were unique, since they were herbal and botanically infused, and I wanted to help him find a home for them in the market,” says Rock, a wine lover whose wife, Kate Rock ’89BUS, co-owns a California vineyard. In 2016, cofounders Lyon, Rock, and Arley Marks, a hospitality-industry veteran, opened Enlightenment as a full-scale production meadery with an adjoining tasting room and nightclub, called Honey’s, inside a former repair shop in Brooklyn’s Bushwick neighborhood.

As the company’s primary mead maker, Lyon is inspired by the drink’s connections to ancient alchemy and the natural world. “We’re continuing the tradition of looking at the fruits and herbs that grow in your local environment and combining them with honey to produce elixirs,” says Lyon, who sources his ingredients from the New York area. Enlightenment’s raw honey comes from an apiary in the Finger Lakes, and the botanicals, including sumac, dandelion, yarrow, and chamomile, are purchased from local farmers or foraged by Lyon and his staff upstate.

Enlightenment’s natural meads, which contain approximately 12 percent alcohol (comparable to standard grape wine), are made from unpasteurized honey that undergoes “spontaneous fermentation.” Rather than adding commercial yeast, the honey and fruits are left to ferment on their own with the wild yeast colonies that are naturally present in the ingredients, stimulating the process. “Making wine can be very industrialized and forced, much more about chemistry, or it can be more like having a garden or compost heap where you’re controlling the inputs and atmosphere and allowing a complex network of organisms to do the work,” says Lyon.

Mead is not terribly difficult to make (our Neolithic ancestors figured it out) as long as you have the right ingredients, he adds. “You can make a pretty good mead at home in a bucket if you have good honey and are paying attention.”

All of Enlightenment’s meads are dry, rather than sweet, and, according to Lyon, they appeal to a variety of palates. Lyon recommends starting with Night Eyes, a sparkling mead fermented with cherries, apples, rose hips, and foraged sumac. “It’s fruity, very dry, and super fun,” he says. Those seeking more floral flavors, he suggests, should try Memento Mori, a dandelion wine. Mead lovers and the mead curious can order any of Enlightenment’s bottles online or visit Honey’s, where straight mead and mead-based cocktails are poured late into the night.

As mead and natural wine grow in popularity, Enlightenment is in the process of bringing bottles to more stores, bars, and restaurants within and outside New York City. “People are starting to understand that consuming natural, local products without added chemicals doesn’t just make you feel better about what you’re buying but actually tastes a lot better,” says Lyon. “I think more and more people are drinking less but drinking better, and that’s really good for everybody.”

This article appears in the Spring/Summer 2023 print edition of Columbia Magazine with the title "Drink Local."