Eric Kim ’15GSAS learned to cook without looking at a recipe. As a kid in suburban Atlanta, he used to tune in to the Food Network after school and then head to the kitchen to replicate what he saw. But mostly he watched his mother, Jean, an intuitive home cook, who used to conjure from “taste memory” the flavors of South Korea, her homeland. She’d add a pinch of this and a sprinkle of that, tweaking it until she made it her own.

“In Korean it’s called your sohn mat, or ‘hand taste,’” Kim says. “It’s everything you put into your food — your soul, your memories, your history with that dish. You can’t just write it down.”

But, curiously, Kim has made a name for himself doing exactly that: at just thirty-one years old, he is already a prolific and versatile food columnist and recipe developer. A staff writer at the New York Times and a regular contributor to Saveur, Food & Wine, Food52, and the Food Network, Kim introduces hungry readers both to dishes that celebrate his Korean heritage, like umami-rich vegetable stews and salty-sweet beef bulgogi, and to his creative versions of American classics, like root-beer-glazed ham and caramel-apple pudding. So when he decided to write his first cookbook, he knew that he wanted to focus on the middle of his culinary Venn diagram — the hybrid cuisine that he, like many other kids in immigrant families, grew up eating. The result, the best-selling Korean American, is a testament to the way that cooking can knit two cultures together and a moving tribute to Kim’s family, especially Jean.

Kim, who lives in New York City, started working on the cookbook right as the pandemic hit, which turned out to be serendipitous. He had planned to move home to Atlanta for a month to work with his mother on the kimchi chapter. That month turned into a year. “Cooking together was like a big knowledge exchange,” he says.

A lot of Jean’s knowledge, Kim points out, was built over years of experimentation and improvisation. When Kim’s parents immigrated from South Korea to Georgia in the 1980s, it wasn’t easy to find soy sauce in the local supermarket, let alone things like gochujang, the chili paste essential to Korean cooking. But, as Kim writes in Korean American, “scarcity breeds innovation.” Kim’s mother learned to substitute ingredients with what she could find on the Publix shelves — swapping jalapeños for shishito peppers and wrapping ground beef and American cheese in seaweed for a new kind of kimbap.

Though Kim was always enthusiastic about cooking, he never thought of it as a career option. He studied literature and creative writing as an undergraduate at NYU, then started a doctoral program in English at Columbia, where he focused on twentieth-century American novelists, like Faulkner and Steinbeck. Not ready to commit to academia, he ended up leaving the program after completing two master’s degrees. “At that point, I had really only known school,” he says. “And I couldn’t shake the feeling that there was something else out there for me.”

Kim took a job doing data entry at the Food Network, where he had interned in college. “It sounds dreadful, but it’s how I learned to write a recipe,” he says. He worked his way up, eventually heading up digital programming there, and then moved to Food52, where he wrote the popular Table for One column and started experimenting with more personal essays. One particularly touching article was about the fraught night Kim came out to his parents, and the kimchi fried rice that his mother lovingly made the next morning.

“It was the most intimate thing I had ever written,” Kim says. “Now I think of food as an entry point. You can use it to write about family, culture, history, politics. It’s present in everything.”

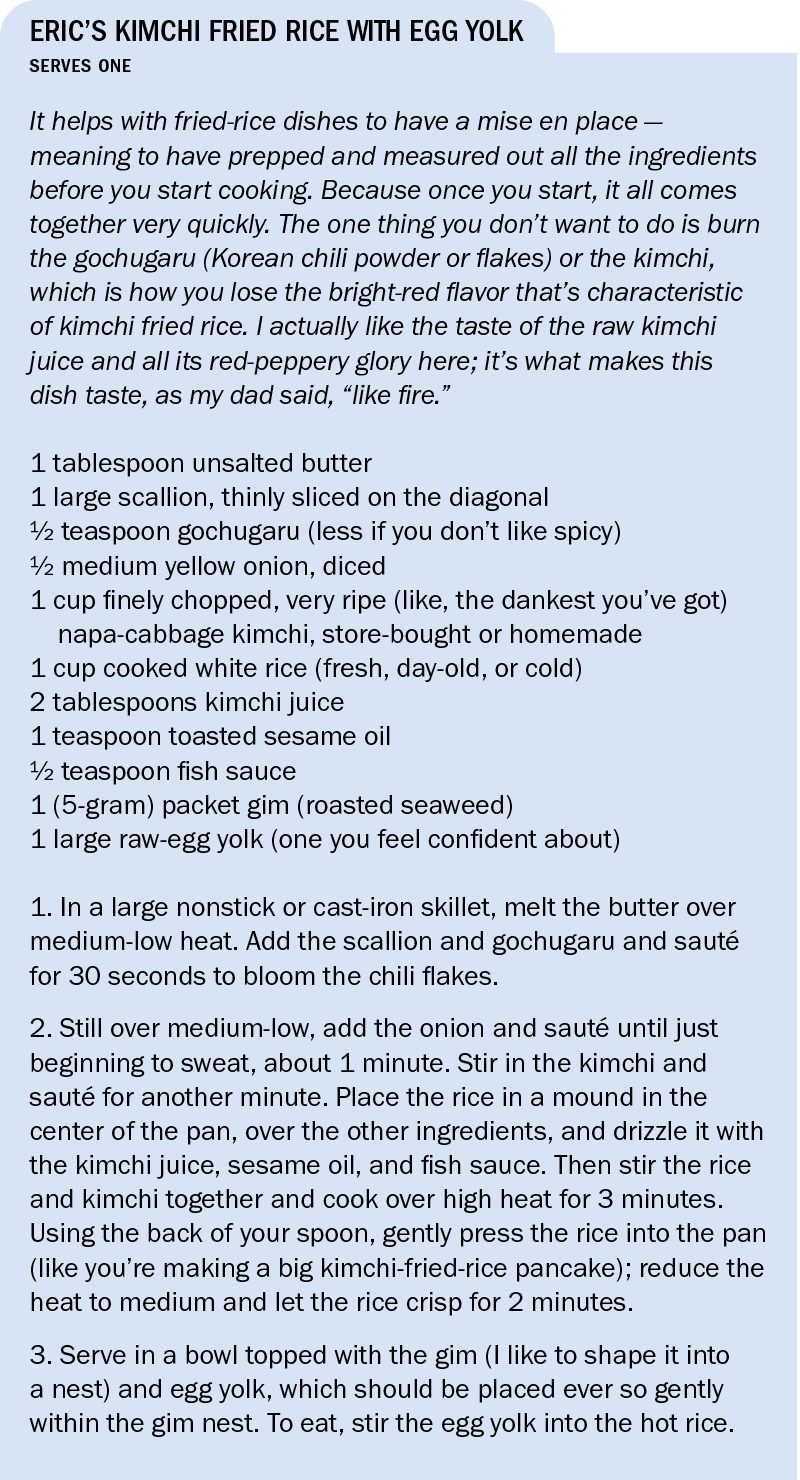

That expansive view of food writing is evident in Korean American, which is studded not only with tempting recipes and sumptuous photos but also charming family stories, thoughtful meditations on immigration and community, and even erudite references that nod to Kim’s Columbia years. While writing about his decision not to include his mother’s recipe for fried rice, for example, Kim alludes to the critic Harold Bloom’s concept of “anxiety of influence” — the fear of being overshadowed by your forebears while you’re trying to make something original. “This is not my mother’s kimchi fried rice,” he writes. “This is mine, and it tastes comforting in a different way, in the way that one might feel when finally leaving the nest.”