The streets were quiet then. Few people. No dogs.

More random wandering chickens than ever, though.

There was a curfew, but there weren’t enough cops around to enforce it.

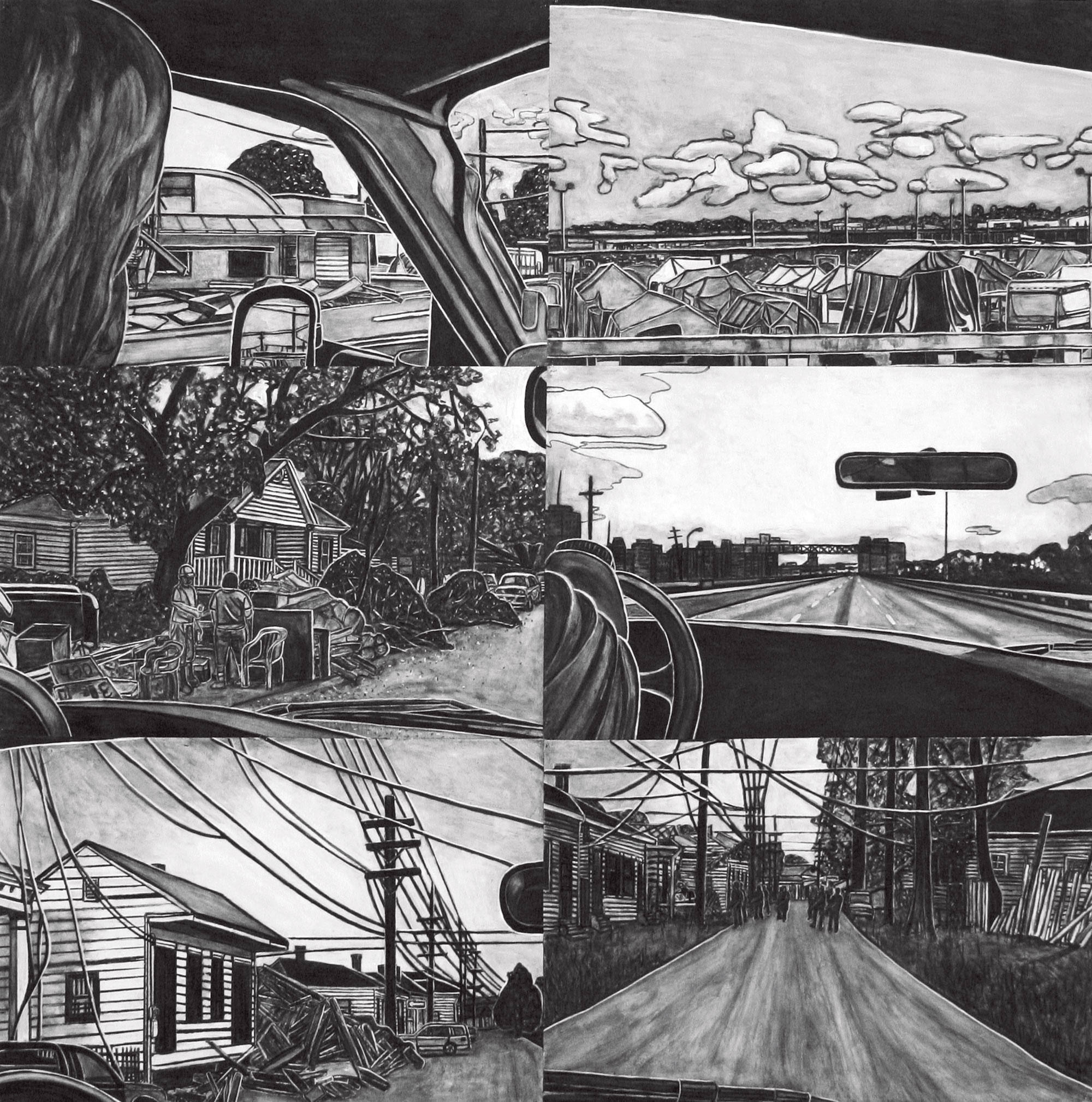

Still, there was that vague feeling that you could be pulled over while following your headlights through the stench of receded floodwaters and dead things, en route to a nighttime gathering of the “huddled masses,” as one friend called the guests at her post-K potluck suppers.

We happy few.

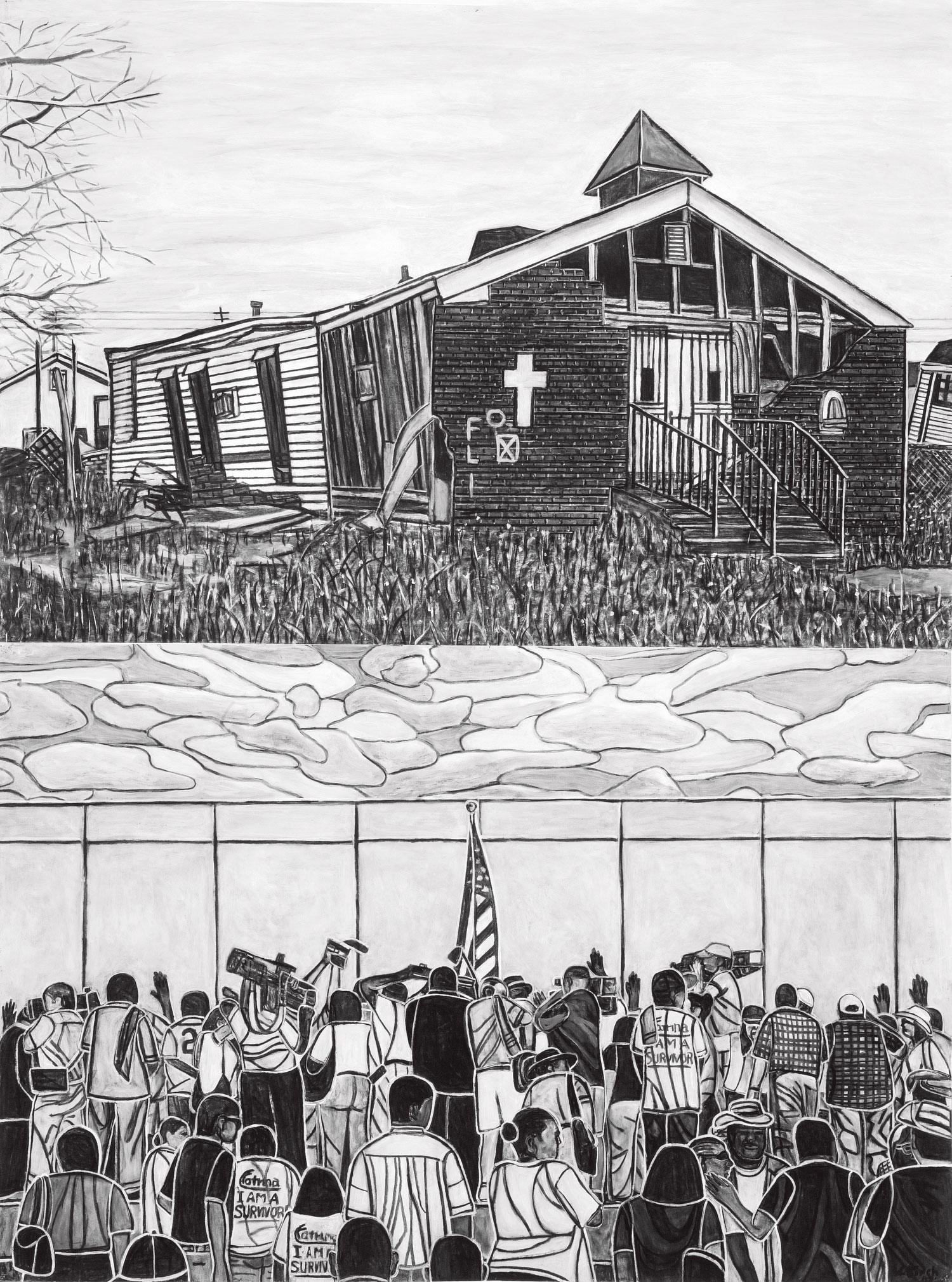

We believed then and ever in New Orleans as a special place. We who had houses and jobs and means felt we had to hold the ground until the rest of our people could make it back home to join the fray.

There were lots of meetings then.

There were official white-collar meetings of experts and politicians and financiers. We watched those mostly from the cheap seats. Then there were the meetings we held among ourselves, plotting strategy to combat the Disneyfication and diminishment of our city, which is what we were certain the experts and politicians and financiers were plotting to thrust upon us.

In the winter of 2006, Loyola University held a series of forums on post-Katrina New Orleans. I sat on a panel with John Biguenet ’03CC, the poet and playwright. “The great enemy of New Orleans culture is American culture,” he said. In other words, our brass bands, Creole architecture, and neighborhood restaurants are at war with pop music, mirrored-glass condos, and Happy Meals.

Oh, what a rallying cry that statement was for us who felt so abused and abandoned by the greater nation. New Orleans was different from America! Better than America! If the United States can boast of its God-ordained exceptionalism, then certainly my proud city-state can do likewise. “Buy us back, Chirac!” proclaimed the Krewe du Vieux in that first Mardi Gras season after the federal levees failed. The national media didn’t necessarily buy into the superiority part, but they expended much ink and airtime explaining how different we were from America proper: how much poorer, how much blacker, how much — how shall I put this? More quaint? Less sophisticated? Less modern?

I’ve quoted Biguenet’s statement often. But even as I write this, my old understanding of what happened to us on August 29, 2005, is giving way to a new view, a view less exceptional. We New Orleanians have our own ways and rituals, but, alas, our situation was and is American — all too American.

The failure of the federal levees during Hurricane Katrina was the worst disaster to hit my city since the Supreme Court’s 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision, which upheld segregation under the doctrine of “separate but equal.” But to relegate the flood-related events and their aftermath to the corner of the national memory reserved for those rare, outlying exceptions is to do a great disservice to the country. For as has flooded New Orleans, so has flooded the nation.

Growing up, we never evacuated during storms.

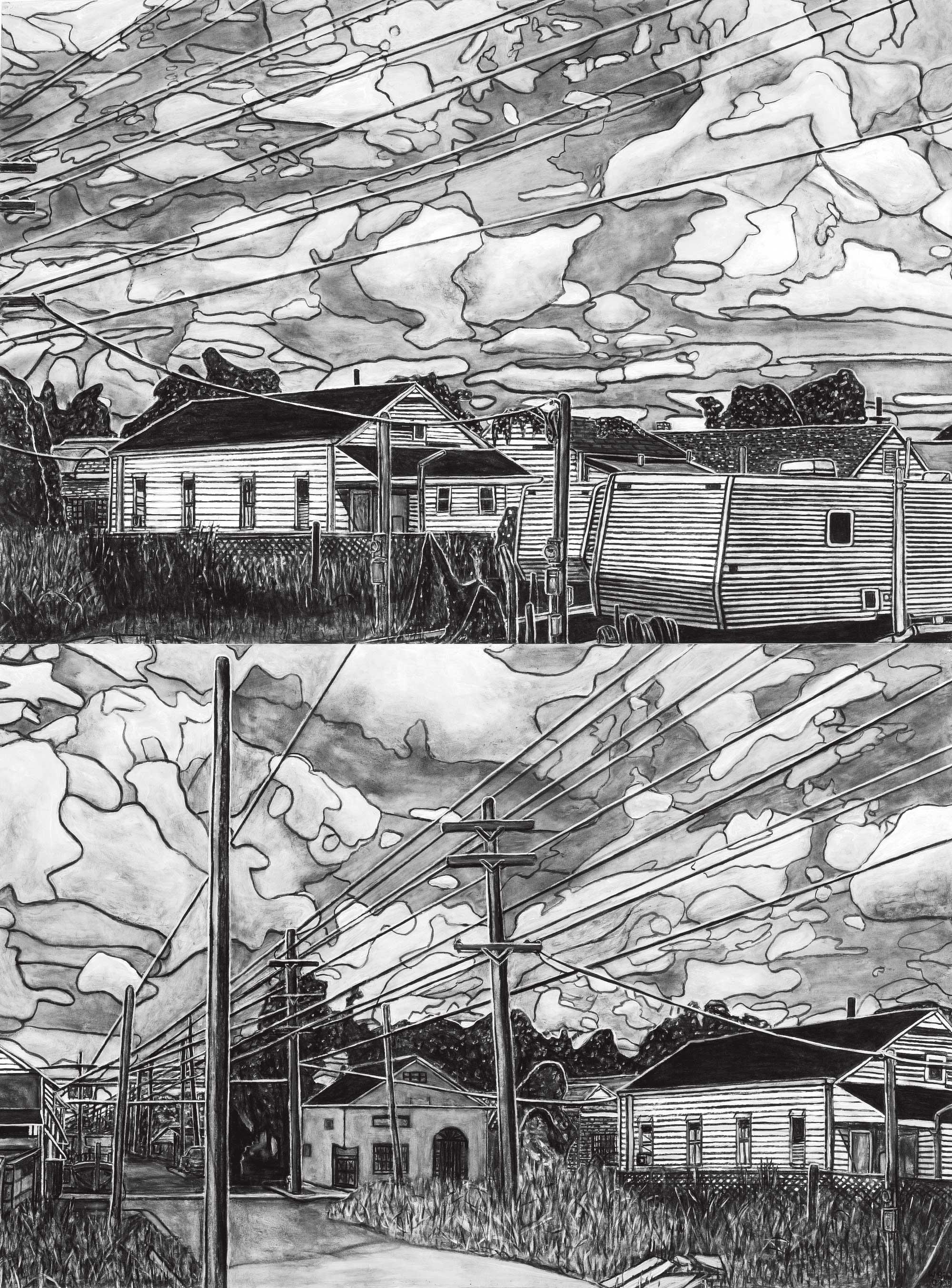

I wrote that in my Times-Picayune column in the aftermath of Tropical Storm Cindy, roughly two months before Katrina hit. After reading those remarks, Sidney Fauria, a coastal-oceanographer friend, showed me what had changed. Driving through St. Bernard Parish, an area that borders both the city of New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico, I saw the coastal erosion. Wetlands and cypress swamps had given way to dying tree stumps and open ocean. Hurricanes gain strength over water and lose strength over land. The ocean’s encroachment is a major factor in the increasing strength of hurricanes in recent years and the increasing vulnerability of coastal and even inland populations. Since 1932, Louisiana has lost an area of land roughly the size of Delaware. The land that remains continues to erode.

And then there are the petroleum and pipeline companies. In 2013, one of the levee boards charged with overseeing flood protection in much of coastal Louisiana sued ninety-seven of them, charging that they had failed to repair the damage done by the canals they had dredged for their oil pipelines. Those canals allow salt water to creep in and destroy the vegetation that holds the land together. A federal judge threw out the lawsuit earlier this year. It is being appealed, but whatever the outcome, it’s clear that Louisiana is vanishing into the Gulf of Mexico. Add to that rising sea levels, which result from global warming and the melting of the glaciers. These factors leave Louisiana particularly at risk, but we are not alone.

The flooding that happened on the East Coast during Hurricane Sandy was intensified by sea-level rise. Please forgive me if I saw a glimmer of a silver lining in the misery and devastation that befell the hardest-hit communities. Maybe, I thought, if the East Coast media and financial centers feel the effects of environmental degradation firsthand, they might move the nation to more aggressive action.

I returned to New Orleans about a week after Hurricane Katrina hit. I had two missions. I was working with filmmakers Dawn Logsdon and Lucie Faulknor to complete a documentary, Faubourg Treme: The Untold Story of Black New Orleans, about one of the city’s historic neighborhoods. I was also trying to salvage what I could from my mother’s home. I did the same for a friend who lived a mile or so away, near the London Avenue Canal. The house was nowhere near any beach, but to get to it I had to trudge through three-foot sand drifts. It was in that way that I learned that there was sand several layers beneath the ground and that one of the reasons the forty-year-old floodwalls had failed was that they hadn't been dug deep enough, hadn't been anchored beneath the layers of soil and sand into something solid.

In his 2010 film The Big Uneasy, Harry Shearer interviews engineers and other experts to determine why New Orleans flooded. Their conclusions form a damning indictment of the work done by the US Army Corps of Engineers. These views parallel those reached by the Corps itself. “The hurricane protection system in New Orleans and southeast Louisiana was a system in name only,” the Corps said in its report. “Corps Takes Blame for New Orleans Flooding,” the Washington Post headline read on June 1, 2006. “Army Builders Accept Blame Over Flooding,” the New York Times said. Still, most narratives about the near death of New Orleans have everything to do with natural disaster and nothing to do with manmade catastrophe, engineering failures, or fatal budget cuts. The Big Uneasy is a smoking gun, a national call to action to improve the way the Army Corps operates. Yet the film and its message were largely ignored.

It has taken some retraining, but I’ve learned to avoid the words “Hurricane Katrina” when talking about what befell my city. This isn’t a choice born of political correctness; it’s a matter of scientific fact. The storm that hit the coastal areas of Mississippi and Louisiana in 2005 was so powerful that it leveled neighborhoods, leaving little more than cement steps in places where homes had been. When I returned to New Orleans, which lies between Lake Pontchartrain and the Mississippi River about a hundred miles from the Gulf of Mexico, there were very few houses that had been similarly flattened. It was floodwaters, not storm winds, that doomed my city. It was the failure of the levees, designed and constructed by the US Army Corps of Engineers. The hurricane occasioned those failures. But that flood-control system was supposed to be able to withstand a storm even stronger than Katrina.

In early 2007, the US Army Corps of Engineers reported that there were 122 poorly maintained levees in twenty-seven states and the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico. That statement, released less than eighteen months after Hurricane Katrina, is the kind that one would expect to provoke an uproar around the nation.

It didn’t.

If you’d asked my grandmother, she would have told you that she earned her living “scrubbing floors.” And she’d also have told you how proud she was that her daughter had finished college and, at her insistence, chosen a very practical career in teaching. A practical woman, my mother made sure that her house had all the requisite insurances and that she kept appropriate receipts for big-ticket purchases. So she was optimistic that, if fairly evaluated, her losses would be fairly compensated. Repeated calls to her insurance company resulted in little more than insults gently phrased. Then she hired a lawyer and — voilà. One carefully crafted letter later, she got most of what she asked for, though still less than what she deserved.

Imagine the various circumstances of Katrina evacuees, scattered to distant cities with little access to phones or social networks, let alone legal representation. Imagine if they had the disadvantage of sounding uneducated or “black” or “Cajun” on the phone. People in the worst of these circumstances, no matter how legitimate their claims, might have become so frustrated at the refusal of the insurance companies to honor their policies that they would have settled for the lowball offer. No need to imagine it. That’s what happened to many people. Too many people. Our experience with the insurance companies was not exceptional: “FEMA has taken the unprecedented step of reopening all Superstorm Sandy flood claims because thousands of homeowners said insurance companies intentionally lowballed damage estimates,” reported NPR in March.

Public education in New Orleans, outside the magnet schools, was bad. Even before the flood, the state had enacted a policy that would allow it to take over “failing” schools. After Hurricane Katrina, the state moved even more aggressively to take over most of the Orleans Parish public school system. It stopped paying teachers shortly after the storm. In December of 2005, while our people were still looking for missing relatives, burying their dead, and trying to keep body and soul together, the Orleans Parish School Board fired all its teachers. All.

My intellectual deficits render me incapable of understanding how anyone could improve a school system by firing the mothers, fathers, neighbors, and cousins of the very students they professed to want to educate. When public-school students returned in larger numbers than expected, the state’s new Recovery School District found itself overwhelmed. Students were served frozen sandwiches. In some schools the emphasis was more on security than instruction. Inexperienced young teachers proved themselves to be inexperienced and young. Since then, many of the fired teachers have been rehired.

Most of the schools in New Orleans are now privatized. Fans of charter schools have rushed to proclaim their success in turning around a failing school system. Research on Reforms, a watchdog organization that analyzes the reported progress of New Orleans public schools, takes a dim view of the claims of success: “Despite the ‘achievement gains’ reported during the past nine years by the ardent supporters of this ‘reform’ movement, the RSD-NO still performs below the vast majority of the other districts at the 4th and 8th grades on LEAP [the Louisiana Educational Assessment Program].”

The New Orleans charter-school system, made possible by Hurricane Katrina, is often cited as a model to be emulated by school systems around the nation. But rather than rush to follow us, the nation would be wise to first determine if we are going in the right direction.

When I moved back to New Orleans in 1991, after a ten-year absence, I wanted to live in an old New Orleans neighborhood. A friend who lived in the French Quarter told me, “There are ten reasons not to live here, and seven of them revolve around parking.” So I moved to Faubourg Tremé, a neighborhood that looks like New Orleans, with its Creole cottages; feels like New Orleans, with its houses close to each other and close to the street; and sounds like New Orleans, with its street parades and neighbors talking loudly on their porches. My house is two blocks from the French Quarter, and before the Katrina influx, the only time I had trouble parking directly in front of my door was during Carnival season and on the occasional night when there was a particularly big event in the French Quarter. These days, I often have to park down the street or around the corner.

New Orleans has seen an explosion in the population of immigrants from Latin America, many of whom were recruited from as far away as Brazil to do cleanup work after the flood. These workers were necessary because the government that had flown New Orleanians off rooftops and out of the state didn’t have any interest in flying them back to clean up their own city. But it is not the immigrants from Honduras or Guatemala that are taking up the parking spaces. For Tremé residents in search of parking, and everyday New Orleanians in search of normalcy, the great adversary has been the swarms of hipsters that have descended on our city.

For millennials, volunteering in postdiluvian New Orleans was like a domestic Peace Corps. It was hot, faraway, and foreign. But it had cell phones, air conditioners, cable TV, and English speaking residents. YURPs — young urban rebuilding professionals — came in droves. Many stayed. And why not? The city has always held a certain bohemian attraction.

Contrary to popular myth, New Orleans has never been entirely insular. Many natives and most politicians would gladly bulldoze a historic neighborhood for the promise of a new Walmart or water park. Many New Orleans chefs and musicians continue to cook red beans and play “When the Saints Go Marching In,” but restaurants like Commander’s Palace have always looked beyond the Creole canon for culinary inspiration, and Ellis Marsalis’s first album was, among other things, a modernist tour of time signatures. We dutifully ripped out most of our streetcar tracks like all the other modern American cities, making way for the exhaust fumes of city buses. If you go to a Saints or Pelicans game, you’ll hear the same rock anthems that they play at every other sporting event in the country. We are not unaffected by the national culture.

But for the natives and immigrants who have found “their” New Orleans among the many cultures, places, and possibilities of the city, there is a fear that the new immigrants will change the city, will make it Brooklyn or San Francisco or one of the many urban American areas where gentrification has moved out all the working-class (read “black”) residents. If it were not for the influence of our West African and Haitian ancestors, New Orleans culture would be a pale, bland approximation of its greatness.But many of these descendants are being forced out as rents increase and as the city continues its policy of bulldozing historic buildings rather than renovating them.

Land of Opportunity, a 2010 documentary by Luisa Dantas '03SOA about the rebuilding and gentrification of New Orleans, carries the tag line, “Happening to a city near you.” Sure enough, the 2009 New Orleans International Human Rights Film Festival featured Some Place Like Home, a film about the gentrification of Downtown Brooklyn, which, due to our own influx of these same East Coast trend chasers, is suddenly a city nearer to us than ever.

Post-Katrina émigrés were not the first wave of Americans to my city. After the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, Americans flocked here to make New Orleans the great economic engine that Napoleon had only dreamed about. They sought to systematically destroy Francophone New Orleans and the antebellum black middle class as steps toward making the city the hub for cotton, sugar, and other trade goods. Fast-forward to 1857. The Mistick Krewe of Comus, the first of the city’s Carnival parade crews, is formed, thus giving birth to the city’s modern Mardi Gras celebration. But these founders were not native New Orleanians. They were Americans who had come to the Creole city. Ironically, these immigrants, rather than Americanizing New Orleans, were Creolized by it. There is hope for the city, in that there is hope that the power of our culture can turn these American hipsters into New Orleanians.

As for the Latino immigrants, there is promise there as well. When you read books about Creole cuisine, often the authors, dilettante historians at best, refer to the “Spanish” influence on our food. It took me a while to realize that Spain, in the 1700s and 1800s, included those Spanish colonies in the Caribbean. Much like the Haitians who provided our city with its last influx of Francophone culture after their revolution, I hope that the Hispanophone immigrants from the south — our South — can reinvigorate our connection to those other places from which our ancestors came.

What the nation wants more than anything from the tenth anniversary of the levee failures is closure. America would like to take a minute to reflect on the challenge of Katrina and the imperfect initial response. Then we’d like to sing a long congratulatory chorus, celebrating the triumph of American gumption over horrific circumstances. The politicians and businessmen boast that they have achieved this kind of closure. They are not entirely wrong. There has been a lot of verifiable progress in the past few years. New construction. New residents. New hope.

But I feel like a character in Jean Paul Sartre’s play No Exit. I know what the nation wants to hear, what the nation needs to hear, but I find myself incapable of saying the words. For if the disaster of the levee failures was a disaster felt most acutely by our poorest residents, then an evaluation of our success or failure must, of necessity, evaluate the post-Katrina condition of these very residents. But the poor were generally left out of our recovery schemes. The state’s Road Home program was designed to assist homeowners in their effort to rebuild and return to the city. It even helped owners of rental properties. Yet it made no provisions for the renters themselves.

If you drive the streets of the Lower Ninth Ward, the poster child for the Katrina disaster, many blocks look as if it has been ten months, not ten years, since the catastrophe. As for all the people the government flew out of the city in the weeks after the flood, many have returned — some have not — but there’s no accurate count. The 2010 census didn’t even ask if you were a Katrina evacuee stranded away from home.

While the flood-protection system is stronger now than ever, it’s still not capable of handling a Category 5 storm. Coastal erosion continues virtually unabated. According to Restore Louisiana Now, it could cost $100 billion to save our coast. The state’s entire budget for fiscal year 2014 was $24.7 billion.

I can’t offer closure. I can offer lessons.

I know. You’d rather have closure.