When the English ballerina Margot Fonteyn made her U.S. debut in New York in 1949, the audience fell at her feet. The ballet was The Sleeping Beauty. We know the yarn: A wicked fairy curses a newborn princess to die by a needle prick on her 16th birthday; a good fairy steps in and reduces the hex to century-long slumber; years pass, memory fades, and when Princess Aurora turns 16, the wicked fairy, in disguise, presents the girl with a spindle. The princess jabs her finger, and she and the entire court lapse into a deep sleep. Only one thing can revive this dormant domain: love.

If the story plucked a string in the city’s hardboiled heart, one needn’t look far for reasons. Who, after all, doesn’t like a good fairy tale?

I

Once upon a time, in Cleveland, Ohio, there lived a bright little ballet student named Arlene Shuler. Like many dancers, Arlene began her training at the age of six. Her mother, a dance lover, took Arlene to see the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo whenever that famous company came to town. And each year, mother and daughter flew east to the mecca of American dance, that empire of stages and skyscrapers and fairy dust, to see what the rest of the world had to offer.

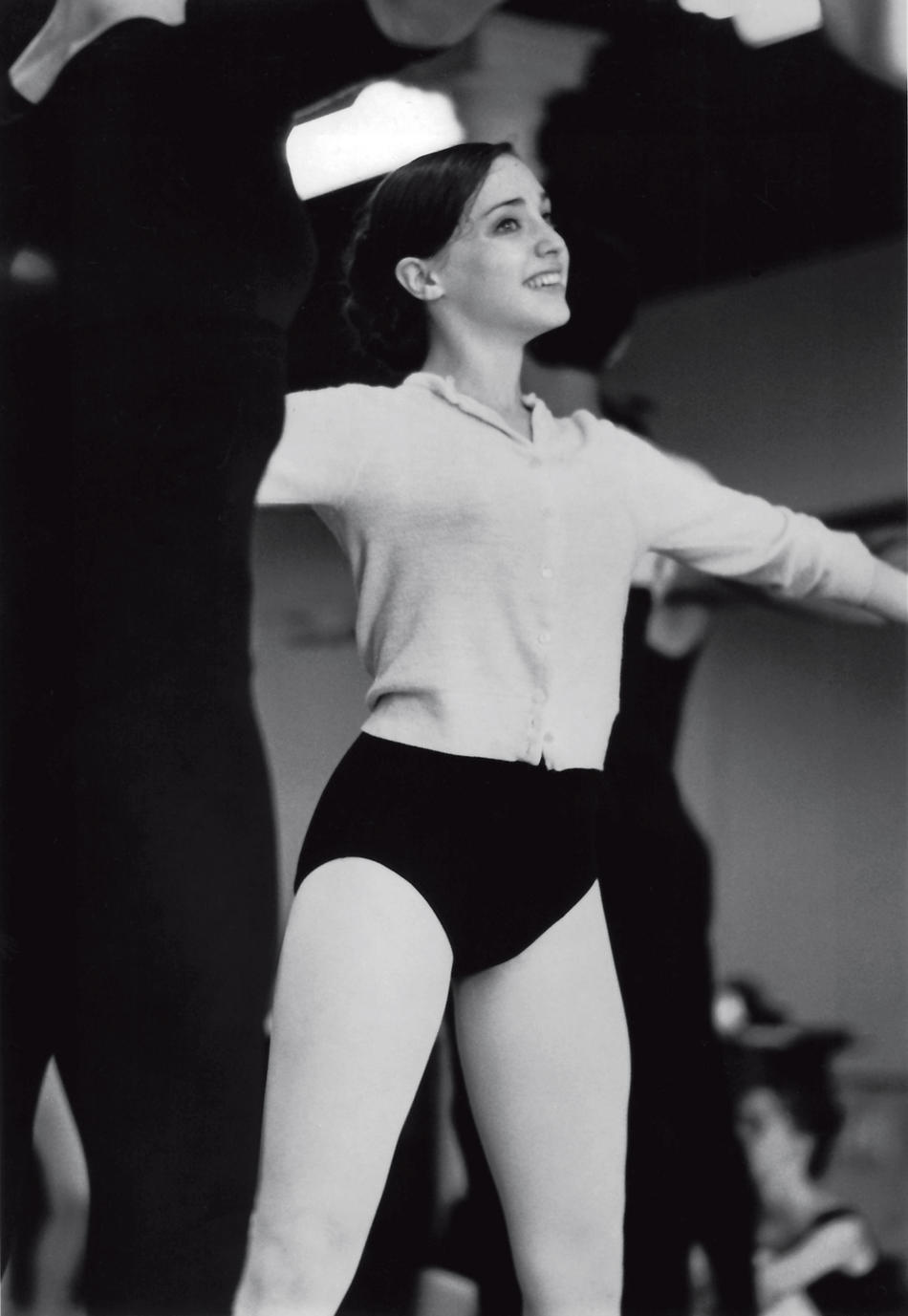

But mostly, Arlene breathed the dust of the dance studio: the wooden barre, the icy mirror, the metrical point of foot, the lengthening of limb, the flow of line, the bruises, the blisters, the accompanist’s waltz, and a taste, upon a grand jeté, of the aerial world, the realm of angels. She became so good that, at 12, she was accepted to the School of American Ballet in New York, founded in 1934 by the lofty prince of culture Lincoln Kirstein and the ballet master and choreographer George Balanchine, in an effort to install this 19th-century Russo-European art form in the land of the Ziegfeld Girls. And so the Shuler family, in support of Arlene’s career, left Ohio and headed for the big city.

Soon after the Shulers arrived, something extraordinary happened. The previous Christmas, in Cleveland, Arlene had watched, live on television, the New York City Ballet’s production of Balanchine’s The Nutcracker. In it, a girl named Clara falls asleep under a Christmas tree, and has the most fantastic dreams. “If I could only be in The Nutcracker!” Arlene had thought. Now, in New York, Arlene was picked to try out for Clara. She went to the City Ballet’s home, a domed building that resembled a Moorish temple, around the corner from Carnegie Hall. There, she auditioned in front of the great Balanchine himself — and got the role! That Christmas season, Arlene frolicked amid snowflakes and candy canes, helped slay a giant mouse, and danced with a prince. How strange and wonderful when a dream comes to life!

But little did Arlene Shuler, or even the Sugar Plum Fairy, know just what lay in store for her under that vault of Spanish tiles . . .

II

“I wanted to create something that would benefit the entire dance community,” says Arlene Shuler inside her office at New York City Center. Shuler is bright-eyed, red-cloaked, poised, and precise. “We look for ways to support the art form and the artist.”

The topic is Fall for Dance, the enormously popular annual dance festival that Shuler launched in 2004, a year after she was appointed City Center’s president and CEO. Shuler’s ascendance from City Center’s stage to its administrative seat is really a story of reinvention: the performer leaving the footlights (in the late 1960s, at 17, she joined the Joffrey Ballet, a year before it became City Center’s resident company) and emerging years later, behind the curtain, in harder shoes and a business suit, with framed vintage playbills on the office walls. Fall for Dance is the apotheosis of Shuler’s twin passions of art and arts advocacy, a 10-day dance party in which a La Guardia-era price of $10 gets you a rich sampling of performances from among 20 established and up-and-coming companies. The 2010 edition featured the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, Bill T. Jones, the Paul Taylor Dance Company, and the San Francisco Ballet, as well as troupes from Brazil, Taiwan, and France. “We sold out in three days,” says Shuler. “In the first day alone, we sold 19,500 tickets. People got in line at 11 p.m. the night before, which, for dance, is pretty remarkable.”

Each night, the crowds surfaced at the 57th Street station, “from the Bronx and Brooklyn, from the far reaches of Flushing and Staten Island, from brownstones and beehive apartments, salesgirls and dowagers and hackies and barmen and garment center stock boys,” as the writer Al Hine described the City Center multitude in 1954. Here, now, was the modern edition of Hine’s jostling wage earners, cramming the sidewalk on West 55th, drawn by a terrific bargain and aroused to civic feeling by the cozy sight of their own diversity. This was New York. The people poured into the mosaic-tiled lobby, diffused through the carpeted halls, and filled up all 2753 seats of the maroon-hued theater.

“One of the objectives of Fall for Dance is to bring new audiences to dance,” says Shuler. “Every year, we take surveys of the Fall for Dance audience. We know that a third are under 30, that about 20 percent either have never been to dance or go less than once a year, and that 40 percent, having been to Fall for Dance, go see more dance. “And” — Shuler’s eyes brighten another kilowatt — “45 percent actually go see a company they first saw at Fall for Dance.”

For a city-owned venue like City Center, which must compete, for starters, with the deluxe, 16-acre performing arts megaplex 10 blocks up Broadway, the cultivation of new audiences is both a moral and economic imperative. Shuler points to a history of shifting fortunes: In 1964, City Center’s core companies — City Ballet and City Opera — left their birthplace at West 55th for the paved deserts and soaring glass of the new Lincoln Center.

“City Center had to reinvent itself,” says Shuler. “The Joffrey Ballet came, followed by Alvin Ailey and Paul Taylor in the 1970s. But since it’s a union house it’s expensive to perform here, and in the ’80s and ’90s not as many companies could afford it. [The Joffrey Ballet left in 1995.] Another impetus behind Fall for Dance was to bring new companies to City Center.”

In the past seven years, more than 140 dance companies have appeared at Fall for Dance.

“Many companies that make their debuts here get picked up and go to other venues like the Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival or the Kennedy Center,” says Shuler, for whom nothing pleases like a dance company getting donors or a new agent or a gig at another spot after being seen at City Center. “Fall for Dance,” she says, “has been very successful in helping the companies as much as the audiences.”

III

None of it was inevitable.

Not the fever of Fall for Dance, or the swooping, rippling white birds of Matthew Bourne’s Tony-winning Swan Lake, or City Center’s Encores! musical-theater series that revives rarely heard works of Sondheim, Berlin, Porter, Weill, Rodgers, Hart, and Hammerstein; not the tile mosaics, the terra-cotta dome, the three large dance studios with their stucco walls, or the grand old theater itself, with its battery of lights, a proscenium arch inscribed 90 years ago with the Arabic greeting Es Selamu Aleikum, and a stage upon which, on a weekday afternoon, the cast of Swan Lake, many in sweatpants and T-shirts, rehearsed a dance of the swans: bodies rose and glided along a violin’s hair, then landed, stopped, listened, nodded, laughed at the director’s wit, waited for the next cue, and were aloft again, so that it was impossible, in that hidden moment of tinkering, on the stage where Balanchine assembled his angels and Stokowski summoned Stravinsky and Robeson played Othello for Hine’s shmata workers, not to shudder with a horror of the wrecking ball; not even the Young People’s Dance Series, in which artists from City Center’s resident and visiting dance companies visit between 40 and 50 schools throughout New York, and the students, in turn, come to City Center for a special matinee performance (“You see those yellow buses lining up on 55th and 56th Streets,” Shuler says, shaking her head, and she doesn’t have to finish the sentence) — nothing as sweet as that — had any hope of existing, but for interventions of the sort that children know through the stories they hear at bedtime.

The Mecca Temple opened in 1923 as a lodge for the Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine, or Shriners. The nonreligious fraternal order was cofounded in 1870 by Dr. Walter M. Fleming and an actor and Freemason named William Florence, who got his festive, Arabic-themed notions while touring Cairo and Algiers. After the financial crash of 1929, the Shriners fell behind on their taxes, and the building, designed by architect Harry P. Knowles and the firm of Clinton & Russell (William Hamilton Russell was trained at the Columbia School of Mines in the 1870s), reverted to the city. For the next decade it lay asleep, and in 1941, this ornamented meetinghouse, with its arabesque ceilings and ghosts of fez-wearing revelers, was set to be demolished. Enter Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia, music lover, who envisioned turning the space into an affordable, city-owned “temple for the performing arts.” Hizzoner waved his wand and got his wish. Or rather, he got his wish and waved his wand: On December 11, 1943, La Guardia, on his 61st birthday, dedicated the City Center for Music and Drama, and, baton in hand, led the New York Philharmonic in “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

After the war, Lincoln Kirstein, who had enlisted, returned to New York. In 1946 he and Balanchine founded Ballet Society, a subscriber-only dance troupe that, like the pair’s previous attempts in the ’30s to establish a viable American ballet company, struggled to get off the ground. But the excellent quality of the project didn’t escape the eye of Morton Baum ’25CC, a former city councilman and tax adviser to La Guardia (in the 1930s he formulated the first New York City sales tax), who was now chairman of the City Center financial committee. In 1948, Baum approached Kirstein and offered Ballet Society a residency at City Center. Kirstein, craving fiscal stability and artistic freedom, eagerly accepted. The New York City Ballet was born.

In 1952, Kirstein became City Center’s managing director, presiding over a golden period when Balanchine and Robeson played to Kramden and Norton, and all was roses under the tiled dome until another Lincoln popped up. With the rise of the gigantic, Rockefeller-funded palace on West 65th, a rumbling could he heard within the mosaic walls. In 1964, with the approval of Kirstein and Baum, City Ballet and City Opera moved to the new Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, and La Guardia’s temple, stripped of its angels, lapsed into another dangerous languor. By the late 1970s, there was again talk of the swinging steel ball. And then, at that urgent hour, another fairy stepped in: City Center chairman Howard Squadron ’47LAW, an influential lawyer and cultural leader who was able to secure municipal funds to fix up the place. That led to the city’s decision, in 1983, to grant the building status as a New York City landmark. A dragon was slain.

But only the building was saved. The institution would soon face other battles.

IV

“I had been doing it for so long that it became who I was,” says Arlene Shuler. “My identity was being a dancer.”

For the first two decades of her life, Shuler had never thought about the future. There was the barre, the mirror, the stage, the music, the gift of flight. What more could a mortal desire? While others went off to college or started families, Shuler stayed in her slippers, doing what she knew best. This was before dance companies offered programs allowing dancers to take college courses, and by the time Shuler concluded that the future, now so much closer, did not hold greatness, she faced the crisis of purpose known to anyone who does one thing with single-minded effort for many years and then must give it up.

“It is very hard to make that transition,” Shuler says, a tug in her voice that suggests a process that never fully ends. “It took me a couple of years after I finished dancing to figure out how I could go to college.” Shuler didn’t want to be a freshman with a bunch of 18-year-olds, and since she had a life in New York, the School of General Studies at Columbia was a natural fit. As a student, Shuler supported herself with secretarial work, and decided that she would need an advanced degree to do something “more substantial.” She applied to law school, thinking it would provide her the most flexibility. The Columbia Law School accepted Shuler a year early: With an inner discipline molded in the dance studio, Shuler regained some time.

After her first year of law school, she got a summer job in Washington, D.C., as an intern at the National Endowment for the Arts. That was the turning point. “I thought, ‘I could be an arts administrator.’ I realized I could combine my background in the arts and my love for the arts with my education.”

Thus began a dancer’s second act: Shuler learned and performed the vital function of fundraising, which she characterizes as “another way to enable the arts to happen.” For 11 years she worked at Lincoln Center, first as vice president of planning and development, and then as senior vice president of planning and external affairs. After that, she was executive director of the Howard Gilman Foundation, a $400 million charitable organization devoted to the arts, medical research, and environmental conservation. “Philanthropy is the flip side of raising money,” says Shuler, who has a way of packing big ideas into a nutshell. “It enables artists and organizations to produce their work.”Although she found philanthropy “rewarding,” she feels “most effective and engaged when I can actively build and support programs with which I’m directly involved.”

When Shuler came to lead City Center in 2003, she knew all about the institution’s resiliency. What she didn’t know was that somewhere in the kingdom, another dragon was being born. This development was especially menacing to an organization that relies on private donations for one-third of its operating budget. But when the beast reared up in 2008, and the economy performed its big tombé — all in the middle of City Center’s $75 million capital campaign to raise money for renovations — Shuler had to respond.

“We began to see the handwriting on the wall in September 2008, right before Lehman Brothers fell. I came back from vacation and I met with our staff and said, ‘OK, let’s come up with a list of things we can cut if we need to cut.’ We didn’t cut any of the core programs because I think the worst thing to do in a recession or time of economic stress, when you still need to raise money, is to cut programs. We are a performing arts institution; what we do is on the stage. So, we tweaked around the edges, in ways that weren’t necessarily apparent to the public: costumes, marketing, doing one brochure instead of two. Ways that wouldn’t affect our core operations.”

Not every purse-string holder would have been so faithful. Lincoln Kirstein’s comment that Margot Fonteyn, of all the ballerinas of the 20th century, “most embodies the art of pleasing,” might equally apply to Shuler. The faces in the crowd at Fall for Dance attest to that: Already the festival is a seasonal must-do, one of those events, like Shakespeare in the Park or the unveiling of an iPhone, for which people camp out overnight. The dance world has taken note of Shuler’s vision. In 2009, she received the prestigious Capezio Dance Award, given yearly since 1952 by the dance apparel manufacturer to that individual or institution whose “innovation, creativity, and imagination . . . bring respect, stature, and distinction to dance.” Past recipients include Martha Graham, Jerome Robbins, Alvin Ailey, Rudolf Nureyev, and, in 1953, Lincoln Kirstein.

“It feels like completing a circle,” Shuler has said of her return to City Center. It’s a ripe simile for a purveyor of the rond de jambe, but Shuler’s circle encompasses more than her own history. It arcs from the dawn of the temple itself — almost 100 years past — to the point, just months away, of its latest renaissance.

V

On March 16, 2010, City Center unveiled plans for its dramatic restoration. The first phase, completed last year, replaced the stage floor and revamped the dressing rooms. The second phase will occur this year from March to October, while the house is dark, after which patrons will enjoy additional restrooms, a second elevator, a restored and expanded rococo-Morocco lobby, a refurbished lounge, improved sight lines, all new seats, and better wheelchair access.

“The theater will be very beautiful and much more comfortable and will provide an enhanced experience for the audience when we reopen in October,” Shuler says.

Shuler knows a few things about revivals. Certainly, she reinvented herself after she stopped dancing, but it’s tempting to imagine that the seeds were planted long before that. One can go all the way back to Cleveland, when Shuler was a nimble sprig of seven. That year, the Royal Ballet came to town, and Shuler, with her mother’s support, got a tiny part in the production. Her job was to carry the train of the lead ballerina’s cape.

With a grace and sureness beyond that of the average first grader, Shuler lifted the cloak and followed the magnificent and enduring princess onto the stage. Then she laid the fabric at her feet.

The dancer was Margot Fonteyn. The ballet was The Sleeping Beauty.