When Michael Novak ’09GS was twelve years old, he developed a stutter so severe that it rendered him almost mute. Ordering dinner at a restaurant was an impossible task; trying to answer a question in class was torture. “It was awkward, scary, and, most of all, completely isolating,” Novak says. “I wanted desperately to communicate, and I couldn’t.” Novak, who was taking jazz and tap classes after school, soon found that he could channel his frustration into movement. The more he fought to express himself, the better dancer he became. In other words, Novak says, “dance became my voice.”

Today that voice is stronger than ever, and Novak has just been given a megaphone to amplify it. Earlier this year, four months before his death at eighty-eight, the legendary choreographer Paul Taylor named Novak, thirty-six, as successor and heir to his modern-dance empire. As artistic director, Novak will head up Taylor’s three dance companies — the Paul Taylor Dance Company, which performs only works by Taylor; Taylor 2, a touring company dedicated to showcasing Taylor’s work to audiences around the world; and Paul Taylor American Modern Dance, which presents new and historical works by other choreographers alongside Taylor’s own. He will also oversee the Taylor archives and the Taylor School in New York.

“And I’ll continue to dance with the companies,” says Novak, laughing over iced coffee and fruit at a café across from Lincoln Center, where he’s about to head into a four-hour rehearsal. “I just might never sleep again.”

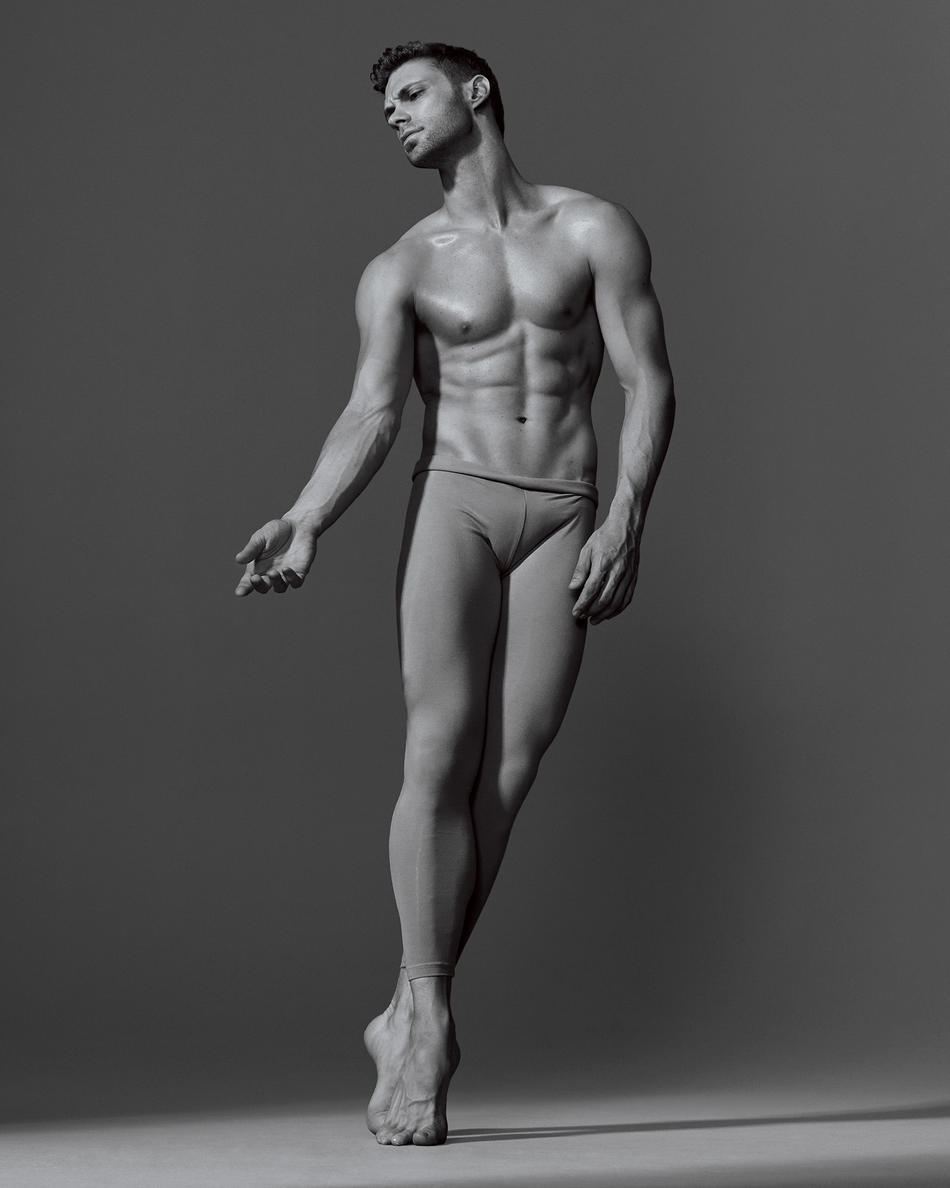

There’s no trace of a stutter left in Novak’s speech; in fact, it’s almost impossible to imagine him as an awkward teenager. He’s confident, funny, and Disney-prince handsome, with frosty-blue eyes, a chiseled jawline, and perfectly sculpted hair. He sits with military posture, even in a casual coffee shop, and rarely breaks eye contact.

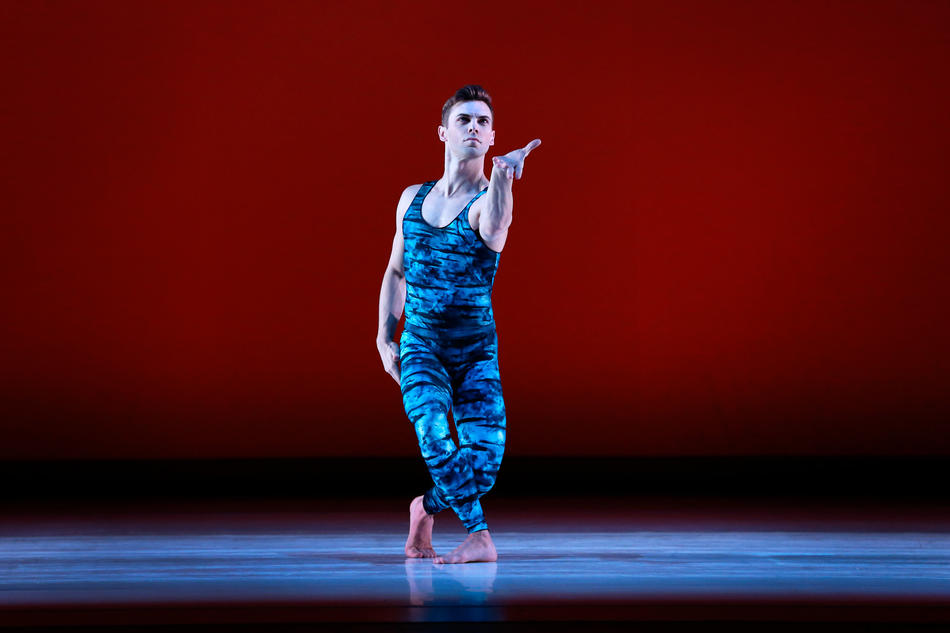

Novak joined the Paul Taylor Dance Company in 2010 and quickly became a standout. In his debut season, he was nominated for a Clive Barnes Award (a top honor for young dancers and actors). For the 2018 season, a striking photograph of Novak dancing solo decorated the company’s program covers and was featured in its advertising (“frankly, I never thought I’d see myself in the New York Times at all, let alone in a full-page ad in tights,” he says). He’s performed fifty-six roles in Taylor dances, thirteen of which were created for him. Still, for most in the dance community, the announcement of Novak as Taylor’s successor was unexpected.

“I think it’s safe to say that no one saw this coming, least of all me,” Novak says. “For the first few months, I felt a physical wave of shock every time I thought about it.”

John Tomlinson, the executive director of the Taylor Dance Foundation, has said that the decision was surprising on two levels. For years, Taylor had said that he had no plans to name a successor at all — rather, he planned to create a committee that would determine the company’s artistic future after he died. The foundation pushed Taylor to reconsider, fearing it would be difficult to fundraise for and build excitement around an organization with such an uncertain path. But many thought his heir would likely be a dancer further into his or her career, who had been with the company longer.

Still, Tomlinson thinks Novak was an inspired choice. “Michael is passionate and articulate about the Taylor repertoire and its contribution to modern dance,” he says. “He’s a student of dance history and has already demonstrated a deep concern about supporting future choreographers. There’s no question that he will leverage this passion, along with sheer talent, dance knowledge, and energy, in working to advance Paul Taylor’s vision of American modern dance.”

Novak grew up in a suburb of Chicago in a family that appreciated music, theater, and all things creative. His father was “a copywriter, consultant, and fiction writer … a real artistic soul,” Novak says. His mother, the executive assistant to the vice president of a steel company, loved musicals and would sing show tunes with Novak as she cooked dinner (“our favorites were Phantom of the Opera, Les Misérables, and Jesus Christ Superstar,” he says). Neither of Novak’s parents were dancers, but they were supportive when their son expressed an interest.

“I tried a bunch of team sports and wasn’t great at any of them, so I was looking for an outlet for my energy,” Novak says. “A dance studio opened near my house, and I started taking classes. It was the right fit from the start.”

As Novak worked to overcome his stutter — he credits hours spent with a speech therapist as well as his burgeoning dance career — he grew more confident both in and outside the studio. In high school, he was president of the drama club and earned starring roles in almost every musical, winning an all-state drama award for the role of David in Bob Randall’s play David’s Mother. He also frequently took the train into Chicago for more-intensive dance classes.

At eighteen, Novak enrolled at Philadelphia’s University of the Arts, where he planned to major in dance and theater. Though he had a solid background in modern dance, jazz, and tap, Novak quickly realized he would need more training in the fundamentals of ballet if he wanted to dance professionally. He withdrew from University of the Arts and enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of Ballet, where the rigors of practices and performances soon took a toll on his body.

“I basically started to develop shin splints immediately and then ended up with stress fractures in both legs,” Novak says. “It was excruciating, physically and mentally. I realized that it was in my best interest to quit dancing and take care of myself.”

Novak was twenty-three years old and had given more than a decade of his life to dance. Suddenly he had to imagine an entirely new future for himself. “It’s not an unusual story for a dancer, but it was devastating nonetheless. I really thought I was never going to dance again,” he says. He moved to New York and applied to two nontraditional programs to complete his undergraduate education — New York University’s Gallatin School of Individualized Study and Columbia’s School of General Studies. Columbia immediately won him over. “I remember going on my campus tour at Columbia, and I just knew,” he says. “I thought to myself, this is the soil that I need to root myself in for the next few years.”

Novak was drawn to Columbia’s arts programming as well as the Core Curriculum (“at that point in my life, I was mostly looking for a strong liberal-arts education,” he says). But what really swayed his decision was the school’s large community of dancers, many of whom were in similar places in their careers and lives. “I found myself in a network of artists who were not just creative but also intellectual. People at Columbia thought like me and communicated like me. I knew immediately that I had found my kin.”

Novak entered as a double major in dance and religion and became involved in a new campus group called the Columbia Ballet Collaborative, which was made up of retired ballet dancers. Novak was doing an independent study in choreography, and he focused a semester on crafting a piece for the collaborative. With his injuries healed, Novak started performing with the group and soon assumed the role of artistic associate.

Through the collaborative, Novak also started working closely with two Barnard professors who specialized in dance history — the late Mary Cochran, who chaired the dance department, and Professor Emeritus Lynn Garafola — and decided to cross-register for classes there.

“I remember Michael as a very curious student. He was obviously a talented performer, but he also wanted to understand the context of what he was performing,” Garafola says.

Under Cochran’s and Garafola’s tutelage, Novak became deeply immersed in dance history, eventually dropping his religion major and writing his thesis on dance photographer George Platt Lynes. “It was largely inspired by a series of nude photographs that Lynes took in 1948 of Nicholas Magallanes and Francisco Moncion in a loose interpretation of George Balanchine’s now iconic Orpheus,” Novak says. “There’s so much in this one series — fashion, surrealism, nudity, homosexuality, portraiture — and the dancers’ bodies take on a truly mythical status. I argue that Lynes’s work is the most important collection of dance photography of the twentieth century.”

Novak had planned to go on to graduate school, for a master’s in arts administration or an MBA. But his legs were getting stronger and less prone to injury, thanks in part to Columbia dance classes. During his senior year, he performed the classic Nijinsky ballet Afternoon of a Faun, as produced by Garafola, who was also serving as his thesis adviser.

“It’s a complex dance,” Garafola says. “It’s choreographed as a moving frieze, with the kind of poses you would see on a Greek vase. Michael had both the technical skill and the imagination to infuse the poses with movement. I knew immediately that I had found my faun.”

For Novak, the performance turned out to be a seminal moment. “I was dancing this incredibly iconic role, in a room full of the world’s most eminent dance historians. And I realized that I still might have something left to give,” he says. “By the time I graduated from Columbia, I had decided to try to pursue a professional dance career one last time.”

Cochran, a former Taylor dancer, thought the company might be a good fit for Novak. At her suggestion, Novak started taking classes at the Taylor School while he was still at Columbia and was accepted into its summer intensive program. “I just fell in love. I couldn’t get enough of Paul’s movements, of the theatricality — there’s an emphasis on line and technique, but there’s always the freedom to move,” Novak says. “I also really responded to the emotional range of his dances. He has very funny pieces and very dark pieces. And the body of work is so huge that I could spend years growing into it. I’d never get bored.”

A spot opened in the company in 2008, the year before Novak graduated from Columbia. He made it to the final round of auditions, but he didn’t get the job. “Then there’s this awkward waiting period,” he says. “You don’t know if another spot will open the next year or in five years.” While he waited, Novak took whatever work he could find, which was particularly challenging since he had graduated during the biggest economic downturn since the Great Depression. “I was a personal assistant. I taught body-conditioning classes. I was dancing with at least three companies at all times. I taught ballet and jazz and modern,” Novak says. “I was twenty-seven, and I was getting tired of scraping together money for health insurance and for student loans. I was craving stability.”

In 2010 — sooner than he was expecting — Novak got a call to say that another spot had opened at the Paul Taylor Dance Company. He auditioned again, and this time he was in. Though Novak had been dancing seriously for over fifteen years, he says that joining the company was one of the hardest things he had ever done. The company spends about a third of the year touring, a third rehearsing, and the last third in what it calls the New York season (“I think of New York as our final exams for the year”). Not only did Novak have to master the bulk of Taylor’s extensive repertoire, he also had to get used to the lifestyle of a touring dancer: “There are so many things you don’t think about. How to dance when you’re jet-lagged. How to stretch in an airport when your plane is delayed. How to stick to your nutrition and cross-training when you’re in Oman, for example.”

Novak says he spent his early years with the company watching as many rehearsals and performances as he could. “I’ve always loved watching other dancers,” he says. “Even at the beginning, it never felt intimidating. It was exhilarating to be able to learn from these incredible artists who were now also my peers.”

Though he says that every role he’s performed with the company has made him a better dancer, he has a particular affection for Fibers, a dance that Taylor created in 1961. “We performed it in 2013, which was the first time it had been produced since the sixties. The costume was very intricate — a fencing mask with striped panels over the eyes and plastic material around the body. Dancing while I was basically bound by plastic was a completely unique, almost terrifying experience,” Novak says. “But what really made it special was that it was my first ‘Paul role’ — that’s what we call roles that he danced himself.”

Now Novak is stepping into a much bigger “Paul role.” As the company’s first artistic director, he doesn’t have much of a playbook to follow. In fact, he says, it’s unusual for an active dancer with a company to assume such a role; often it’s a former dancer who has already stepped into a management position. Unlike Taylor, Novak does not have any immediate plans to make his own dances. “I do have a background in choreography, but I see myself more as a curator for now,” Novak explains. He says he is planning, programming, and thinking about ways to bring dance to new audiences. As a devoted student of modern-dance history, he’s also excited about resurrecting dances that haven’t been performed in decades. “The first thing I did was to take out all my dance-history books from Barnard and Columbia,” Novak says.

To prepare for his new job, Novak also immersed himself in the Taylor archives, developing a deep knowledge of the company’s nearly seventy-year history. In the first few months of Novak’s tenure, Taylor was his mentor, sitting with him during rehearsals and going over notes on the performance together and meeting at Taylor’s Lower East Side apartment to talk through the 2019 and 2020 seasons.

Since Taylor’s death in August, the weight of Novak’s new role hits him from time to time. Novak had hoped to have more time to spend apprenticing under the renowned artistic director. But Novak says he takes comfort in recalling the way Taylor approached him about the job.

“It wasn’t a question: it was a directive. That signaled to me that he trusted me to do this, and that he believed I could,” Novak says. “Paul Taylor left us an incredible body of work, inspiring generations of artists and audiences with his wit, musicality, humor, and humanity. When I think about the fact that this legendary artist gave over his entire legacy for me to protect and preserve, I really can’t imagine a higher calling.”