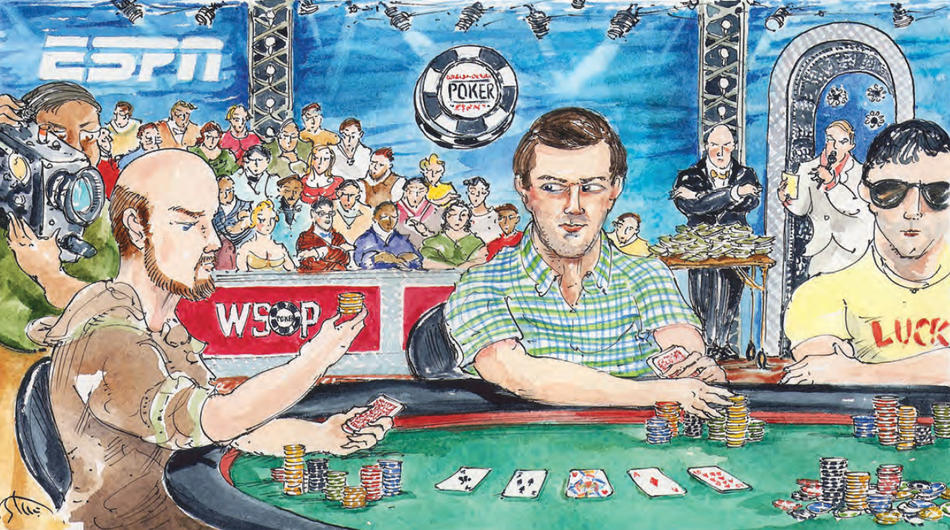

David Benefield is about to drop. After seven long days of intense mental focus at the Rio All-Suites Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas; after sleepless nights rocked by extreme emotional swings; after sweating it out under the lights and ESPN cameras amid a field of 6,352 other competitors, the twenty-seven-year-old General Studies student is exhausted, ecstatic, and in disbelief.

He is one of nine players left sitting.

In front of him, on the green felt table, lies a stack of candy-colored tournament chips: 6.34 million (not a dollar amount, but more like points). While the pile looks impressive, Benefield faces an uphill climb. His winnings are less than those of the eight other players who have advanced to the final table. The chip leader holds a gargantuan 38 million. But as the old poker saying goes, “All you need is a chip and a chair.”

Benefield has both, as well as a chance to turn his $10,000 entry fee into a major score and a huge comeback in poker’s biggest event, the World Series of Poker. Having qualified for ninth place and pocketed just over $900,000, Benefield will return to the Rio hotel on November 4 as one of the “November Nine,” vying for the gold bracelet (poker’s green jacket, its championship belt) and a prize of $8.3 million.

“Poker is different from the majority of casino games in that you are playing against other players, not the casino itself,” says Benefield, a native of Fort Worth, Texas. “As long as you make better decisions than your opponent, you will win money in the long run. I try to consistently make good decisions and limit my own mistakes while thinking about the best ways to exploit the tendencies of my opponents.”

Benefield has won $633,243 in his live-tournament career, but like many players, his early forays at the table were tough lessons rather than cash cows. After his first game, with his wallet considerably lighter, he went home and ordered some poker books. He consumed as much information as he could, and soon began winning consistently against friends.

In 2008, Benefield broke into the world of tournament poker with several nice finishes, including seventy-third place with $77,200 in that year’s world championship main event. This year, he has already improved on that finish.

Just making the final table will be lucrative. Because he can finish no lower than ninth, Benefield will earn at least $733,224. That could ease some of the pressure, but not all of it.

“Poker is incredibly stressful on an emotional level, which negatively impacts the physical,” says Benefield, who studies political science and Chinese. “In my earlier years playing professionally, I was not good at dealing with large monetary losses. They hurt me a lot mentally, and I would tend to turn inward. I wouldn’t want to hang out with friends or hit the gym. Instead, I would sit at my computer and figure out how to avoid losses in the future. I have gotten much better about this over the years.”

Before November’s main event, Benefield plans to spend some time in Vancouver working through game situations with his friend, tournament poker superstar Jason Koon, as well as playing online poker and some other major tournaments in Barcelona and Paris.

But his heart will be in Texas. The Lone Star State has a rich poker history, with legends like Doyle Brunson and Amarillo Slim Preston dominating in the game’s early tournaments.

What would it mean to be the next in that line to bring home the gold?

“It seems only right,” he says, “that a Texan should win the world championship of Texas Hold ’Em.”