Urquhart here. I might look a bit drawn and peaky, but that’s because I have just watched, in unbroken succession, all twenty-six episodes of the American version of House of Cards (it’s rather habit-forming, I’m afraid), a political thriller whose subject is Power. If I may say so, the show’s creator and writer, Beau Willimon, has reinvented the 1990 BBC miniseries in ways I scarcely could have imagined, back when I was putting a bit of stick about in Parliament as chief whip.

Yes: I, Francis Urquhart, the original F. U., precursor to Willimon’s Francis Underwood (and Kevin Spacey’s Underwood, I should say), have cleared my busy schedule to taste the Machiavellian juices of Willimon’s concoction. Now, while I still have my wits about me, I introduce to you the story of a young artist who became a playwright, jumped into the waters of campaign politics, wrote a play based on the adventure that became a major motion picture, signed a most unorthodox deal to remake House of Cards for an outfit called Netflix, and then, at thirty-five — the age of presidential eligibility, come to that — shot like a Bloodhound missile to the very heights of American television.

I use the term television loosely, of course.

“The show’s subject is much bigger than political power,” says Beau Willimon ’99CC, ’03SOA during a break from writing the third season of the Netflix drama House of Cards.

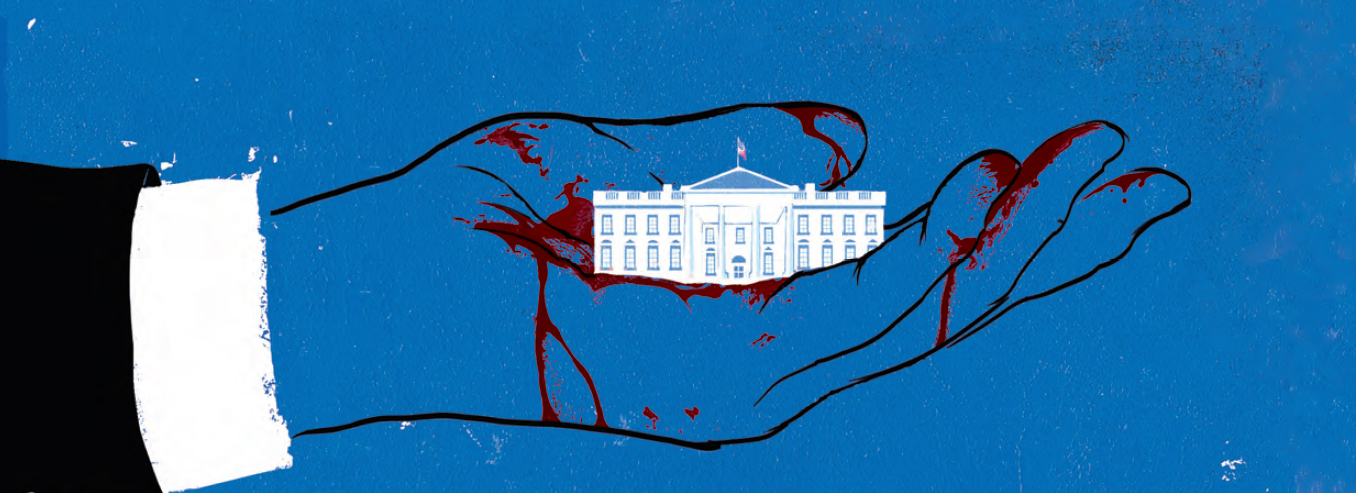

“It’s about power in all its forms. Power over one’s self, and the power dynamics of relationships — friends, spouses, family. I think political power, to a degree, is an attempt to master our fate. For politicians, it’s an attempt to cheat death: ‘I can’t cheat death completely, but I can control as much of the universe as possible while I’m here.’”

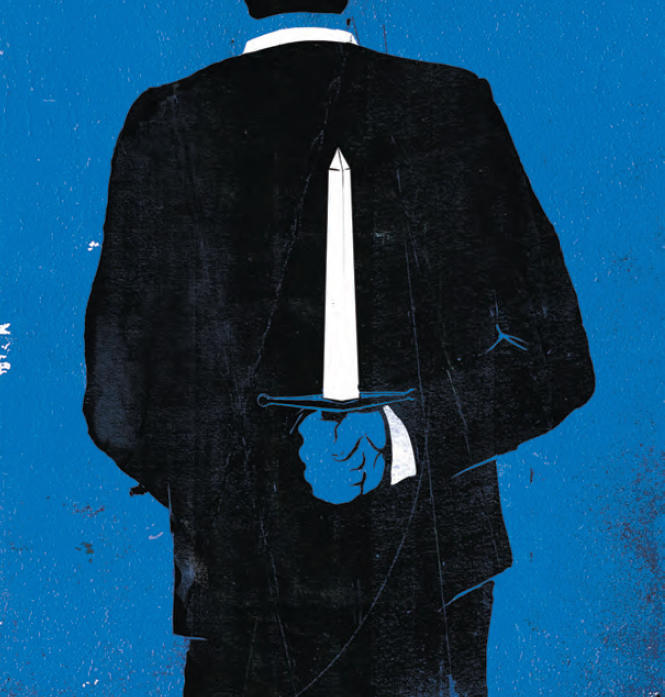

In the show’s first episode, Congressman Francis Underwood (D-SC), snubbed for a promised cabinet post by the new president, plots a course of vengeance that will mimic the cold calculus of his legislative style. “Forward: that is the battle cry,” he says in one of his Richard III–style asides, delivered with a Dixie drawl. “Leave ideology to the armchair generals, it does me no good.” Underwood has a way of summing things up. Early in season two, while taking a breather from his battle, he relaxes in his window with an electronic cigarette. “Addiction without the consequences,” he says. Of all his pungent epigrams uttered to the fourth wall, this one speaks less to Underwood’s condition than to ours: having been made complicit by his direct appeals, we then participate in his evil with the luxury of immunity. House of Cards may hook us with top-notch storytelling, but the rush is provided by the show’s brand of wish fulfillment: Underwood’s wicked manipulations and forceful takedowns provide vicarious satisfaction (if not inspiration) for anyone who has toiled in a bureaucracy. Other characters fight other addictions in House of Cards, but power is the strongest intoxicant of all.

“It’s an interesting paradox,” Willimon says. “A lot of people think of power as a form of control, and yet addiction to power in some ways removes control from the equation. It’s a balancing act. The more you become addicted to power, the less control you have over yourself, because of what you’re willing to do to acquire it or maintain it.”

1995. AUTUMN. A rowboat glides along the Harlem River, propelled by eight Columbia oarsmen. Two members of the crew seem different from the rest. A scruffy hint of the free spirit about them. The hair a little long.

One is Jay Carson ’99CC, of Macon, Georgia. The other is Beau Willimon, of St. Louis.

Carson’s kick is politics. At thirteen, he was riveted by the 1992 presidential campaign, wowed by the brains of Bill Clinton’s young communications director, George Stephanopoulos ’82CC.

Willimon is an artist. A painter who could draw before he could talk. He wants to use the canvas to tell stories.

The two met at freshman orientation, drawn to each other by a shared sense that no one else wanted to hang out with them. They quickly became best friends.

1997. Carson sees a flyer in Hamilton Hall advertising an internship with George Stephanopoulos. As Clinton’s senior policy adviser, Stephanopoulos has left the White House after the president’s second-term victory over Bob Dole, and returned to Columbia to teach.

Carson applies for the internship and gets it. While Stephanopoulos teaches a seminar on presidential power, Carson spends hours in the International Affairs Building, doing research for his mentor’s political memoir All Too Human.

Stephanopoulos sees his protégé’s hunger for electoral politics and gives him a tip. “There’s a little-known congressman from Brooklyn who’s running for the Senate,” he tells Carson. “He’s in third place right now, but I know him from my time in the White House, and he’s going to win. Go work for this guy.”

The candidate is Chuck Schumer. He is running against the powerful three-term Republican senator Alfonse D’Amato. Stephanopoulos makes a phone call, and Carson joins the campaign.

Though he’s never worked on a campaign before, Carson senses that this one is special. Much later, he will remember it as “one of those times when a group of people comes together and it’s all the right people — the next generation of talent in a party. That was that race.” He tells Willimon how much fun it is.

Willimon, in his paint-splotched pants, is interested. He shows up at Schumer headquarters in Midtown, ready for action. The senior staff christens the two friends “Beau and Luke Duke,” after the freewheeling Georgia cousins in the 1980s TV show The Dukes of Hazzard. (Carson is a little miffed that he’s lost his name, while the newcomer gets to keep his.) The friends work tirelessly, a pair of unpaid interns too naive and energetic to say anything but “Yeah, absolutely” when asked to do something.

For instance, Schumer has a campaign stop in Buffalo tomorrow, but the shipment of yard signs has failed to go out. The last planes have left La Guardia, so there’s no way to overnight them. It’s a cold night, sleeting and snowing. The senior staffers look around the war room and see Carson and Willimon sitting there. “Hey, guys,” one staffer says, “can you drive these yard signs to Buffalo tonight?” Carson and Willimon look at each other, then at the staffer. “Yeah, absolutely.”

Beau and Luke Duke drive their own rented version of the General Lee all night to Buffalo, get the signs there, and meet the Schumer motorcade the next morning.

In an upset, Schumer wins the election. Carson, who will become press secretary for the presidential runs of Howard Dean (2004) and Hillary Clinton (2008), still calls the Schumer race “the greatest campaign I’ve ever done.”

Willimon, too, remembers it as “an incredible experience. Your candidate wins, and you feel that in your own minuscule way you made a difference, and helped change the face of the country.” After Schumer, Willimon goes on to work with Carson on Bill Bradley’s presidential campaign of 2000, and Hillary Clinton’s Senate run of the same year. His idealism and optimism are riding high.

Then comes the Dean campaign.

“SUBVERT THE TROPE.” These words pop from a sign plastered in an office in New York’s financial district. The walls are otherwise covered with dry-erase boards and corkboards. This is the writers’ room, where Beau Willimon is bunkered this summer with six handpicked writers, in the midst of a seven-month writing binge that will result in thirteen more hour-long episodes of House of Cards.

The writers spend the first few weeks plotting a grid (episodes one through thirteen across the top, characters down the side), looking at the season as a whole and figuring out characters’ story lines and the big plot moves. Then they dive in, episode by episode. Each episode takes about six weeks to write. “It’s an intensive process,” Willimon says. “Monday to Friday, eight hours a day. A bunch of brains launching themselves against a wall, hoping to break through. The creative process is always a trial-and-error game. The moment it stops being trial and error is when you’ve gotten comfortable, when you’re not taking risks, when you’re doing things you already know how to do. We endeavor to challenge ourselves to do things we don’t know how to do, and the only way to do that is to bang your head against the wall until you break the wall or the wall breaks you.”

One of the writers in the room is Frank Pugliese, a playwright and scriptwriter who teaches at Columbia’s School of the Arts. Born in Italy, Pugliese grew up in the Italian-American neighborhood of Gravesend, near Coney Island — “a very masculine place with a real vocabulary of violence about it.” His family was ostracized, considered foreigners, outsiders. As a teenage writer contemplating the theater’s empty space, Pugliese wanted to fill it “with language, music, and people that aren’t often seen there,” he says. For him, that meant his Brooklyn neighborhood. “As difficult a place as it was, I wanted to put it in that space and celebrate it and share it with other people who had similar experiences — to say, I know your suffering, I know your joy. We can share that.”

His play Aven’U Boys, about three young Italian-American guys in Brooklyn, was produced off-Broadway in 1993, when Pugliese was twenty-nine, and won an Obie Award for best direction. Though Pugliese went on to a successful career writing for television and film — including winning a Writers Guild Award for his work on David Simon’s TV series Homicide, and writing the HBO movie Shot in the Heart (2001), about the executed murderer Gary Gilmore — he has never stopped writing plays.

Willimon is partial to playwrights. He feels they have an advantage, being steeped in a form in which “you can’t hide, you can’t edit your way out,” and for which there is scant financial reward. “Those are the people I want,” he says. “So hungry they’ll crawl across a desert to tell a good story.”

Pugliese is one of four playwrights in the writers’ room. “The quality and level of the writers is tremendous,” he says. “Some of the best writers in the city, and particularly in the theater, are in that room. Writers who are strong at character, who have a real sense of the subtextual power behind relationships, which provides a lot of energy — there’s a titillation in the subtext between characters that’s fun to watch and even more fun to write.”

Like a musical ensemble, the writers play off each other, riffing, noodling, telling stories, composing. Good is never good enough; there is always a sense that a thing can be better. In such a demanding atmosphere, trust is paramount. “If you’re not allowed to fail in the writers’ room, then why would you bring something in tomorrow?” says Pugliese. “When you do, that’s when the great stuff happens.”

It all starts with Willimon. Television, its literary profile raised over the past fifteen years by shows like The Sopranos, Oz, Deadwood, The Wire, and Breaking Bad, is considered a writer’s medium. The writer runs the show.

“House of Cards is fortunate to have Beau in charge,” Pugliese says. “Beau is there from the beginning to the end, and so carries the story in hand. He’s the protector of that story; he champions it, argues for it.”

And he’s serious about that sign on the wall.

“What’s amazing about Beau,” says Pugliese, “is that he has this strong sense of structure, yet also a profound and courageous ability to experiment and go for it and break rules — to do the unexpected.”

It's caucus time '04 in Iowa, and Jay Carson has a decision to make. The press advance isn’t up to snuff. As Howard Dean’s press secretary, this is Carson’s problem to fix. Carson calls his friend Willimon and asks a big favor.

The past few years have marked a change for Willimon. Back in his senior year of college, frustrated with the narrative limits of painting, he entered the competition for Columbia’s Seymour Brick Memorial Prize for playwriting. His play, which he would later describe as “terrible,” won the cash award. This gave him just enough confidence to keep writing. After graduating, he lived on the Lower East Side and worked odd jobs, then audited a playwriting class at Columbia taught by Eduardo Machado. Machado, who was the head of the playwriting program, saw Willimon’s promise and urged him to apply. Willimon did, and was accepted. Among his classes was a screenwriting course for playwrights taught by Frank Pugliese.

Now a year out of grad school and busy with his writing, Willimon answers Carson’s call. Like Carson, Willimon caught the political bug during the Schumer campaign, and the chance to work for the insurgent candidacy of the former governor of Vermont, whose antiwar message and Internet army have made him the unlikely front-runner in a field that includes John Kerry and John Edwards, is seductive. Willimon moves to Iowa to be the press advance guy for Dean.

“Age-wise,” says Carson, “we were children. I’m still amazed at how much responsibility I had at twenty-six, and wonder why anyone gave it to me.”

Willimon enters this campaign as he did the others — with the highest hopes and deepest desire to contribute to changing the country.

In Iowa, Dean finishes a disappointing third. During a never-say-die speech to his supporters, the candidate unleashes a hoarse battle yell. Microphones isolate Dean’s outburst from the crowd noise, and the media play the clip ad nauseam. A month later, the damage done, Dean drops out of the race. Willimon is heartbroken.

A few years later, Willimon writes a play, Farragut North, loosely based on his experiences on that campaign. The protagonist is Stephen Bellamy, a precocious, ambitious twenty-five-year-old press secretary for a presidential candidate, who falls prey to backroom politics. The play opens off-Broadway in 2008 to excellent reviews, and moves to Los Angeles the following year. The film rights are sold to George Clooney and Leonardo DiCaprio. Willimon is suddenly very hot. Trips to LA, meetings, phone calls. One of those calls is from director David Fincher (Seven, Fight Club, The Social Network), who wants to remake House of Cards, the British miniseries based on a novel by former Conservative Party chief of staff Michael Dobbs and written by Andrew Davies. Willimon watches the show and loves it. He has a million ideas. So does Fincher. The two are in sync. They see it. They hear it.

In 2011, the film version of Farragut North, titled The Ides of March, is released, and Willimon earns an Academy Award nomination for best adapted screenplay. Meanwhile, he writes a pilot for House of Cards, and it doesn’t hurt that actors Kevin Spacey and Robin Wright are attached to the project. He has meetings with the big cable networks, and also with Netflix, an online-streaming and DVD-delivery giant that wants to get into the original-programming game.

Using its subscriber data, Netflix sees potential for a remake of the esteemed British show. Still, the whole thing is a gamble — neither Netflix nor Willimon nor Fincher has done TV before.

No matter. Netflix proposes something extraordinary. As Willimon will later put it, “They made an offer we couldn’t refuse.”

Urquhart here. Still awake. Pity about Dean. And to think that that scream nonsense happened before social media — nowadays a gaffe can finish you off in seconds rather than hours. But a quick death is so much more desirable, don’t you think?

I believe our Underwood would agree. He has no time for such useless things as suffering. A merciful man, Underwood. And Mr. Spacey does get his teeth into a role, doesn’t he, much as Willimon provides the meat. How fitting that Spacey, just before House of Cards, played the lead in a world tour of Richard III, and that Willimon attended the final performance at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. I, for one, find it impossible to watch Underwood’s exploits and not think of dear Richard’s public disavowal of kingly ambition even as he laid waste to those in his path.

But it’s not just the spirit of Richard III dealing from the deck’s bottom in House of Cards. There’s a dash of the Macbeths, and some Iago for good measure. Mostly, though, there is Willimon, whose handsome Underwoods, I feel, are not devoid of morality — there is always a price for getting things done.

I love that woman. I love her more than sharks love blood.

— Francis Underwood

“What draws me to the show is Frank and Claire Underwood,” says Pugliese. “I hadn’t seen a relationship like that on TV. It’s something that everyone on the show, the actors and directors, could get — even its elusiveness, even its sublime mystery. It’s the heartbeat of the show.”

In Francis and Claire Underwood, Willimon’s childless DC power couple, we see an attraction that is narcissistic and tactical, tender and devout, like that of two androids in a corrupt human world who share a singular affinity. Theirs is an open marriage, yet prone to suppressed jealousies both sexual and professional, in which tense conversations are cut short on the stairs by innocuous-sounding yet pointed exit lines. But mostly, their same-species rapport feels like the one thing as powerful as their ambition.

Pugliese hadn’t been in a writers’ room in seven or eight years. Though he’d been working on TV shows and writing plays, the writers’ room scenario meant a serious grind. He’d told himself that only the right marriage would bring him back.

“I met with Beau before the season started,” he says. “We had a remarkable, liking-the-same-things kind of meeting. He reached out and asked me if I wanted to come into the room for this season. I had promised myself that it had to be an extraordinary person and situation. This was it.”

“Kevin Spacey's performance in Richard III hugely influenced the conception of Francis Underwood,” says Willimon. “Kevin was able to bring a humanity and humor to Richard III, one of the more nefarious characters in Western literature, and have him rise above near sociopathy so that you saw someone who was three-dimensional and human and flawed — which doesn’t excuse his actions, but layers them in such a way that they don’t come off as pure evil. That’s something I constantly remind myself of, because we try to do the same thing with Francis. I’ve never wanted Francis to be a mere sociopath — he has to be more. That’s why we have access, glimpses, even if they are few and far between, of his humanity — his moments of vulnerability, his ability to love and even to have compassion, in his own way. The sociopath is incapable of empathy, and Francis is very capable of empathy. He makes the choice, when necessary, to suppress it, but that doesn’t mean it’s not there.”

“We can't pay you much, but it would be really great to have you help out with this. It’s so intricately political, and it’s so important that we get the details right.”

When Jay Carson got Willimon’s call, he was working as executive director of the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group and senior adviser to Bloomberg Philanthropies. It was 2011. Willimon had just signed a deal with Netflix to make House of Cards.

The whole thing sounded a little crazy to Carson, as it might have to anyone who thought of Netflix as the company that conveyed DVDs in red-and-white envelopes, Mercury-like, to your home. Still, Carson was in a good position to help. After the Dean campaign, he had worked four years on the senior staff of Senator Tom Daschle (D-SD); was communications director for the William J. Clinton Foundation; and, in 2009–2010, was chief deputy mayor of Los Angeles.

In some ways, Willimon’s request felt to Carson like the reverse of the Dean situation, when Carson had called on Willimon for help. Carson and Willimon were no longer the guys who said “Yeah, absolutely” at the drop of a hat. But Carson agreed to become the political consultant for House of Cards.

The two friends spoke casually early on. They’d sit around and talk politics, and discuss how things worked. Procedural stuff. Obscure parliamentary rules. Carson knew a lot about Congress from his years with Daschle, and if he didn’t know something, he knew whom to ask.

“The show requires a lot of interaction with high-level people in Washington,” Carson says. “There were some brave and kind people who talked to us in the beginning, when we were just some show that was going to be on the Internet. I called friends in Washington: ‘Can you take us on a tour of the White House? Of Congress?’ Many nice people did that for us.”

As political consultant, Carson reads the outline of a script, the rough draft, and the completed draft, checks it for accuracy, plausibility. Much of the time, he finds, the writers hit the mark.

“The job is becoming harder because the show is getting much smarter about politics,” he says. “It’s also becoming easier, because the writers’ room and the team is getting a much better feel for the world of politics and power.”

One of the many surprises of House of Cards, given its vision of a political system rank with ambition, vanity, and lobbyists, is how many fans it has inside the Beltway.

“People in Washington love it,” Carson says. “They appreciate our attention to detail. We respect the political world and take it very seriously.”

What Netflix offered Willimon was this: two seasons guaranteed up front — twenty-six episodes — and full creative control. It was an arrangement unheard of in television.

“The two-season guarantee was huge,” Willimon says. “It really liberated me as a storyteller because I had a much broader canvas to work on, and I didn’t feel the need to fight for my life the way a lot of shows do on regular broadcast networks week to week. It meant that there were things I could lay in early in season one that might not come back fully until season two, which allows for more sophisticated storytelling.”

This sort of freedom makes Willimon the envy of other TV writers. Next to the average showrunner on network or cable television, who is subject to corporate notes and the tyranny of weekly ratings, Willimon is Butch Cassidy in a world of singing cowpokes.

House of Cards has been a critical as well as a popular success. In 2013 it received nine Emmy nominations and became the first online program to win an Emmy Award — three in all, including best director for David Fincher, whose dark color palette of blues and browns, noirish sensibility, and sharp compositions established the House of Cards style. What also distinguishes the viewing experience is the way it is consumed: in the Netflix model, each season is released all at once, allowing viewers to stream the show anytime, on any Internet device, and to watch in chunks, in dribs and drabs, or in obsessive marathon sessions known by the catchword of the online media-streaming age: “binge-watching.”

Well, yes, quite.

Like lamb stew or marriage, House of Cards is even better the second time around. I have, I confess, gone on another “binge-watch,” and am competent to state that with repeated viewing, the cunning of Willimon’s structure, the design of his tapestry, is all the more evident and impressive. So it goes with any artful narrative, I gather, though we’re not always compelled to have another go at it, are we? Without doubt, part of the House of Cards phenomenon is the ease and accessibility of the streaming technology — you can watch on your phone while sitting on the throne at three a.m. if you must. That’s well and good. But what is the thing, the scent, the food, that so attracts us, that keeps us in pursuit?

Let’s have Willimon answer that.

“I am attracted to the same things a lot of the viewers are — the deliciousness of a man who is bound by no rules. Who has unshackled himself from the law. There’s a reason why Orson Welles said that Shakespeare’s greatest characters were villains: it’s because they give us access to that part of ourselves that says, ‘I don’t have to play by the rules.’ In Francis you see someone who is living that dream.”