Robert Lipsyte’s path to sportswriting was indeed a happy accident. Queens-bred, hard up for summer cash, possessor of a not-exactly door-opening degree in English literature, Lipsyte got a job as a copyboy at the New York Times in 1957. As he explains in his new memoir, An Accidental Sportswriter, he became a peon among “the invisible line of Rhodes Scholars, Fulbright Scholars, and PhD candidates waiting for a job.” Lipsyte liked the crusty, ink-stained curmudgeons who sent typewritten stories whooshing through pneumatic tubes to the composing room. But he hated the job, and aimed for the higher reaches of the word-slinging trade by enrolling at Columbia’s journalism school.

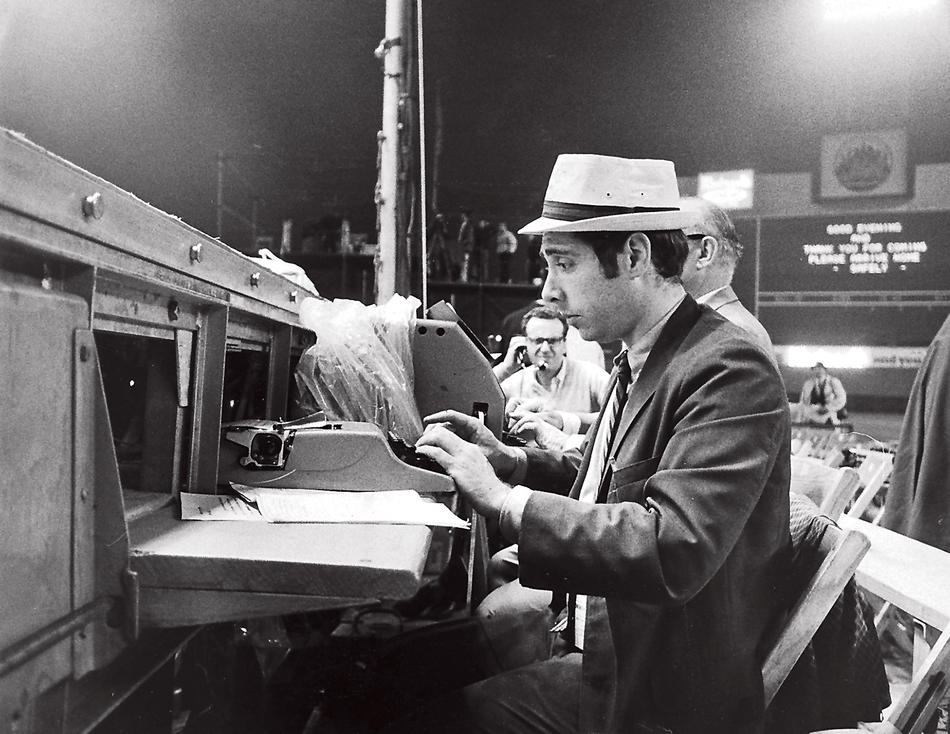

By chance, a slightly better job opened up in sports. The rest is history, with a small h. Lipsyte ’57CC, ’59JRN ended up working at the Times, mostly as a columnist, off and on for almost a quarter century.

By his own account, young Lipsyte was “lippy,” talented, and the kind of nonsport sports writer that the Times was looking for in the late 1950s and 1960s. The incumbents — Arthur Daley, Dave Anderson, even the storied Red Smith — always struck me as a passionless lot: tweedy op-ed wheezers rusticated to a part of the paper known in the business as the toy department. Lipsyte is a honey of a writer, and won the columnist’s mantle, it seems clear, to draw readers back to vigorous and opinionated sportswriting.

He’s funny and irreverent, a nice one-two jab. Here is his coy aside about the boxing stories of A. J. Liebling ’25JRN, now enjoying a modest reputational rebound in smart society: “It would be some time before I began to figure out why so many of the boxing trainers and cornermen who seemed all but mute to me were masters of aphorism for him,” writes Lipsyte after a few months on the boxing beat. “Liebling was a superb writer.”

We read of brushes with Rupert Murdoch and with David Berkowitz, the “Son of Sam” serial killer. In 1977, Lipsyte was serving time at Murdoch’s New York Post, where the word came down that “the Boss wants you to lose those poofter boots.” “Aussie homophobic bully!” was Lipsyte’s reaction and, no, he didn’t ditch his Italian suede shoes. On the next page, when Lipsyte met Berkowitz, being held for psychiatric evaluation, the suspect “smiled, relaxed, told me he did have the power to send destructive forces into my home but would not.”

Lipsyte is a different kind of cat who is attracted to like-striped felines. He returns perhaps too often to his outsider status in the world of Jock Culture. He eschews the “lodge brothers” of the sportswriting fraternity, who see their task as “godding up” the heroes of the age. (Lipsyte on golf writers: “What a crew of house pets!”) “English major” is a broad metaphor for the kind of people not welcome in the sports scribbling fraternity. Or “puke.” That is what Columbia crew coach Bill Stowe called “anyone in 1968 who wasn’t on his boat, which included hippies, pot smokers, antiwar demonstrators, bearded weirdos, guitar players and, yes, English majors.”

“Sort of puke-ish, I am,” Lipsyte confesses.

He seeks out unusual assignments and champions the men and women he relates to. The first of his 20-odd books is Nigger, coauthored with comedian-activist Dick Gregory. Lipsyte was present at the creation of Muhammad Ali, and sticks with The Champ through fat times and thin, generally admiring, never worshipful. He loves Billie Jean King, whom he calls “the most important sports figure of the 20th century,” and he devotes a chapter of this book to the travails of the few professional athletes who have come out as gay, and to the generally chilly reception they received.

Lipsyte likes to pass judgment on people, and doesn’t spare himself or conceal the jagged edges of a tough life. He’s gone three rounds with cancer, and has been married four times. He doesn’t dodge unpleasant truths. For instance, he was the rare sportswriter to note that Mickey Mantle had jumped to the head of the liver-transplant line, even though the ailing ballplayer was a poor candidate for the surgery, and died soon after.

That transgression, and others, catches the attention of “the ultimate lodge brother of our time,” the frictionless Bob Costas, who seeks out Lipsyte for a heart-to-heart conversation. “I was flattered that he had taken the time to mentor me — he was 14 years younger — but irritated by his presumption,” Lipsyte writes.

Costas has a useful message for him: Enjoy. Yes, it’s true that sports “has lost almost all its moral cachet,” in Lipsyte’s bitter phrase. But there is real beauty in the sporting life, and Costas worries that Lipsyte, whom he admires, is willfully blinding himself to moments of epiphany. “I wanted you to be less corrosive; skeptical, not cynical,” Costas says.

There is some truth to what Costas says. There are moments, for instance, when Lipsyte is flagellating himself for not reporting more aggressively on the blight of steroids in sports, when I want to say, “Relax, Robert. Let the world turn without you tonight. You’re talented, you’re a mensch, and you’re alive. You are the happy accident.”