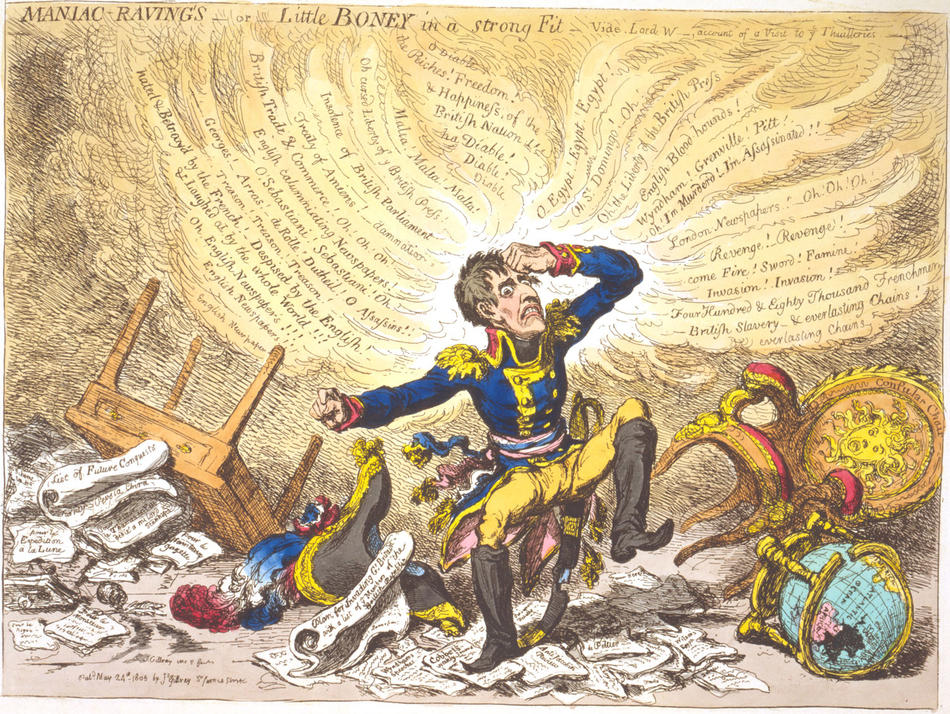

“A pamphlet is no more than a violation of opinion; a caricature amounts to an act of violence,” declared King Louis-Philippe of France in 1835. Were the royal feelings merely bruised by Charles Philipon’s popular drawing of his pointy-wigged, fat-jowled head morphing into a plump pear? Or did he genuinely fear for the stability of his regime? Louis-Philippe was not the only monarch who felt this strongly about the wounding power of cartoons: Napoleon Bonaparte found James Gillray’s caricatures of him as the vain, paranoid “Little Boney” so damaging to his international reputation that he reportedly claimed that they “did more than all the armies of Europe to bring me down.”

Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never harm me, goes the nursery rhyme; why do political cartoons bring the mighty to their knees? That’s the question that Columbia Journalism School professor Victor Navasky grapples with in The Art of Controversy: Political Cartoons and Their Enduring Power. Drawing on his experience as the editor of the Nation and the satirical magazine Monocle, Navasky traces the form across centuries and nations — Hogarth to Hirschfeld, Denmark to South Africa — and collects theories.

Perhaps drawings have the power to act instantly upon the imagination, like a book read at the speed of light. Or perhaps it is the particular genius of caricaturists to seek “the perfect deformity ... to penetrate through the outward appearance to the inner being in all its ugliness,” as the art historians E. H. Gombrich and Ernst Kris wrote in the British Journal of Medical Psychology in 1938. Think, for instance, of the indelible Nixon caricatures of Washington Post cartoonist Herblock: hunched, jowly, with permanent five o’clock shadow. Of course, some subjects are riper for caricature than others, as political cartoonist Doug Marlette observed: “Nixon looked like his policies. His nose told you he was going to invade Cambodia.”

In the end, perhaps the greatest reason the caricature wounds so deeply is that the subject has no adequate way to respond. “The only way really to answer a cartoon is with another cartoon,” writes Navasky, “and there is, for all practical purposes, no such thing as a cartoon to the editor.”