When Henry Hudson first sailed past northern Manahatta Island in 1609, natives peered at him from the banks of an inlet that would one day become West 125th Street. He anchored the ship and invited two men aboard, whom he dressed in red jackets and promptly tried to kidnap. They escaped, but several weeks later, as Hudson’s ship continued north, the same men led a retaliatory strike, rowing alongside the ship in canoes and riddling it with arrows. Hudson’s men fired back with muskets and cannons, killing about a dozen people on water and land. This tale of interethnic hostility serves as a starting point and a through line for Jonathan Gill’s new history of Harlem. “The clash of words and worlds, the allure of blood and money, the primacy of violence and fashion, the cohabitation of racial hatred and racial curiosity — they have always been a part of what uptown means,” writes Gill ’86CC, ’99GSAS in Harlem: The Four Hundred Year History from Dutch Village to Capital of Black America.

Readers who know Manhattan’s broader history will find some of the book’s events familiar, but Gill’s focus on Harlem makes the story fresh. We learn, for example, that after the English conquered New Amsterdam in 1664, Dutch Harlem’s inhabitants resisted; the sheriff refused to swear allegiance to the crown, though he was allowed to keep his job despite declining to perform his duties. Mostly ignored by local English officials, Harlem developed its own culture through local inns, “the most public of places, where different classes, genders, religions, nationalities, political loyalties, and even races met and mixed.” As a result, while Manhattan as a whole was devoting itself to economic development, Harlem remained a play space for downtown New Yorkers, where horse races continued on Harlem Lane (present-day Saint Nicholas Avenue) even as the Revolutionary War began.

Harlem had an early connection to black America, as Gill reminds us: its participation in slavery and the slave trade. A small number of Manhattan’s free Africans lived in Harlem, largely in self-contained communities with their own cultural and social institutions. But half of all white Harlem families owned slaves at the beginning of the eighteenth century, and new laws and regulations constrained both enslaved and free black men and women, preventing them from owning guns, signing contracts, or giving testimony in court.

Harlem’s role in the Revolutionary War was small but significant. George Washington and his aide Alexander Hamilton (who attended King’s College between 1774 and 1776) fortified Harlem against the British in September 1776, and while the Battle of Harlem Heights held off the British only briefly, the psychological victory boosted morale — and Washington’s stature. The neighborhood paid a steep price: two months later the British burned the entire village. For the next four years, Harlem was virtually unoccupied. Only after independence transformed Manhattan into a bustling trading center did Harlem regain its status as a frontier resort for the upper classes. Hamilton built a grand country estate on a thirty-two-acre wooded property between present-day West 139th and 146th Streets and lived there until 1804, when Aaron Burr killed him in a duel in Weehawken, New Jersey. Burr later married a Harlem socialite and moved there himself to enjoy the countryside and the wealthy entertainments of the period.

But Harlem was quickly changing. In the early nineteenth century, downtown industry began to reach northward. Ferry lines, piers, factories, and foundries brought wealth and opportunities for laborers. Farmland was turned into roads and business districts; the country’s first horse-drawn street railway tied lower Manhattan to the Harlem River along Fourth Avenue. The West Harlem village of Manhattanville, founded in 1806, “came to resemble a tiny New England mill town,” Gill writes, “with eighty homes housing five hundred residents, most of whom worked in local tanneries, bottlers, a foundry and a fabric mill, breweries, stables, a hotel, rooming houses, and taverns.” Manhattanville’s success in manufacturing and trade brought its founders positions of influence in the city as a whole, in society and in politics. By the 1870s, most of Harlem had been incorporated into Manhattan politically and economically, if not always culturally.

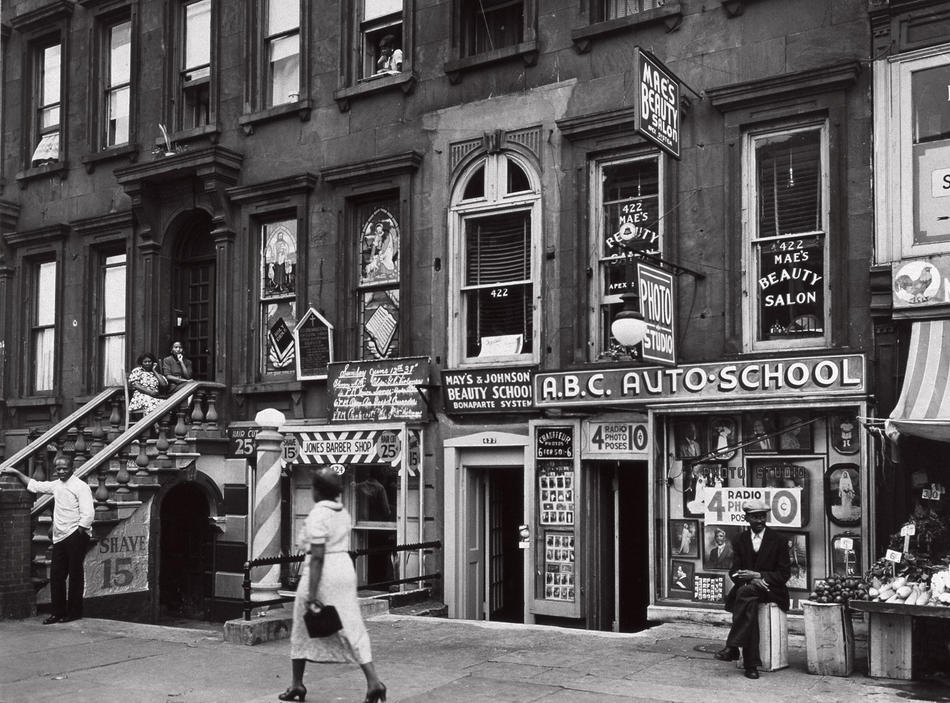

As Harlem’s industry expanded, its population became increasingly diverse. Immigrants from Ireland and Germany arrived in the 1840s and 1850s, followed by more from southern Italy and Eastern Europe. As the fortunes of Dutch, English, and German settlers improved, they moved to nicer parts of Harlem or out of it entirely; Italians and Jews moved up from lower Manhattan to take their place. Harlem’s identity as an African-American community dates to the turn of the twentieth century, Gill writes, when an anti-black riot downtown coincided with a boom in speculative housing and the construction of New York’s first subway. Harlem real-estate agents realized they could charge blacks higher rent than whites, since discrimination limited where they could live, so they lured black tenants as whites left for the Upper West Side, Brooklyn, and the Bronx. Gill acknowledges the concurrent descent of much of Harlem into poverty, but he does not focus his narrative on such discouraging developments. Instead, he traces Harlem’s population shifts by highlighting prominent or colorful individuals, such as the naturalist John James Audubon, the political cartoonist Thomas Nast, and the impresario Oscar Hammerstein, through whose experiences we watch Harlem begin to develop its unique personality.

Harlem is best known, of course, for the Harlem Renaissance, a flowering of black artistic expression that seemed to answer W. E. B. Du Bois’s call for the African-American to become “a co-worker in the kingdom of culture.” The intellectual and political energy of the so-called New Negro, helped along by the Great Migration, which brought hundreds of thousands of African-Americans north between 1910 and 1930, inspired black painters, poets, essayists, filmmakers, authors, and musicians to create art from their own experience. The center of their activity was Harlem. Duke Ellington and Paul Robeson ’23LAW, Claude McKay and Langston Hughes lived and worked there, as did political figures like Marcus Garvey, W. E. B. Du Bois, Walter White, and Adam Clayton Powell (both Sr. and Jr.). It served as a crucible for the truly American art form: jazz. But Harlem’s glamorous high life — never the world of most Harlemites — came to an end with the Great Depression, which devastated black Harlem and set the stage for the political tumult and crushing ghetto poverty to come. By the 1960s, Harlem had become the symbol of black urban poverty and protest.

Even in these years of renaissance and decline, Harlem remained deeply multicultural, its many Puerto Rican, Jewish, and West Indian residents living alongside their African-American neighbors. Discussing George Gershwin and Irving Caesar’s 1919 song “Swanee,” which Al Jolson included in his show Sinbad, Gill writes, “A plantation tune by a Jew in a show about an Arab folk hero was the way they did things in Harlem.” But Gill also flags the undercurrents of nationalism that had always run through Harlem, first by white groups and then by black, which he argues threatened Harlem’s rich and multiethnic artistic culture. Gill describes not only the physical dangers of such nationalism, as in the burning of the Colored Orphan Asylum by white Civil War draft resisters, but also the political dangers inherent in belligerent nationalist rhetoric.

Gill’s narrative style is primarily anecdotal. Readers are introduced to significant or emblematic Harlemites such as Eliza Jumel, a close friend of Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, and Aaron Burr (whom she later married), and the gangster “Big Yid” Zelig, who stood up to Italian mobsters in the early decades of the twentieth century, but who recruited “Dago Frank” Cirofici into his own criminal circle. While fascinating, the focus on significant individuals too often leaves out the experiences of ordinary Harlemites. We hear a great deal about gangs, drug dealers, musicians, political activists, government leaders, artists, and businessmen. We hear far less about those who struggled to get by, to raise their families and improve their lives. Gill writes about the dramatic fight in the late 1960s over Columbia’s plan to build a gym in Morningside Park, but then notes that, according to a 1967 poll, most Harlem residents were unaware of the issue, and that in fact half of those who knew about the plan supported it. What of their experiences and concerns?

Without more complete analysis, we watch history happen without always understanding who is responsible and why. Gill tells us what his eighteenth-century subjects ate and how they celebrated but not how they regarded slavery. As we watch the new nation grow through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, we learn nothing of the systematic exploitations of race and class on which its development relied. When we reach the 1970s and 1980s, Gill depicts Harlem’s sense of hopelessness — its crime and high rates of illness — but fails to explore the deeper causes of these problems. Gill’s tendency to end discussions with questions that he never answers (was the Harlem Renaissance “really a bona fide artistic movement or was it simply a fortuitous gathering of individual talent . . . ?”) only reminds us that the author has given us no framework that we can use to interpret historical events.

Nevertheless, the book is an impressive compilation of material and an evocative story of a place so central to the American imagination. While Harlem’s history may not always be coherent — “change is Harlem’s defining characteristic,” Gill writes — certain overarching themes emerge: a multiethnic population, art and vice, economic challenges, political maneuvering. These tensions, Gill argues provocatively, “have always allowed Harlemites to define themselves not just as apart from all other New Yorkers but as the divided soul of the city itself.”