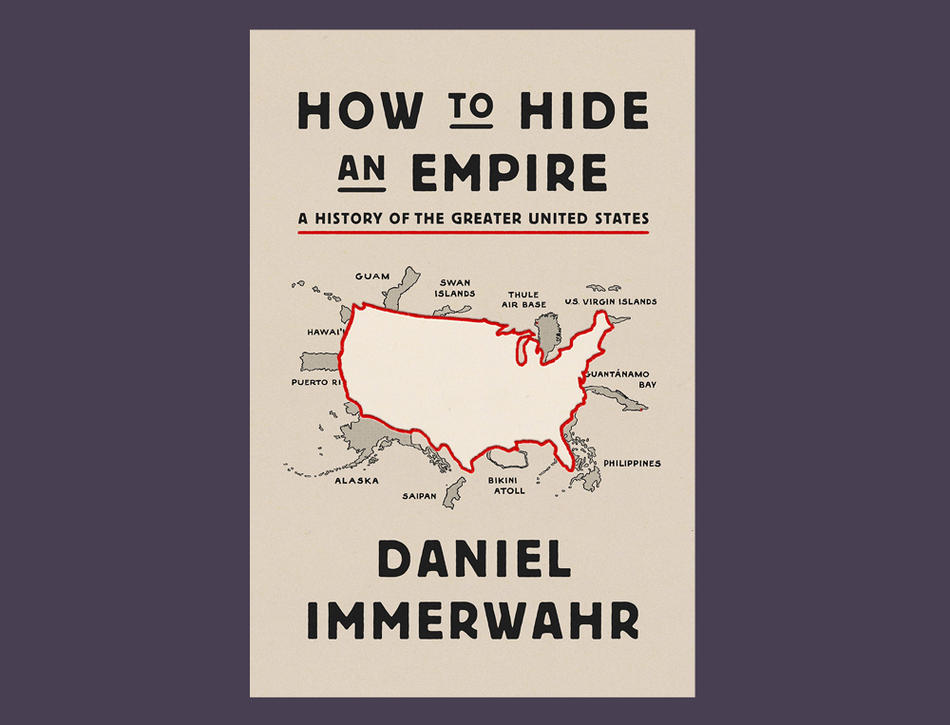

Early in How to Hide an Empire, historian Daniel Immerwahr ’02CC shows us the “logo map” of the United States — the familiar representation of the forty-eight contiguous states. Never mind that the map snubs Alaska and Hawaii; what it never even hints at are the many overseas territories that, at their high-water mark (the end of World War II), were home to a staggering 135 million people and constituted a land mass equal to almost one-fifth that of the United States.

With its attenuated reach, the logo map affirms one of the cherished myths of American identity: that the world’s greatest democracy doesn’t “do” empire. Laying waste to this comforting notion, Immerwahr knits together dozens of disparate, often harrowing stories into a larger, eye-popping narrative of American imperialism; his exhaustive account of this hidden history is a revelation.

The urge to expand, of course, goes back to the country’s founding, although Immerwahr — a professor of history at Northwestern — points out that racism may have acted as a check on early expansionism. When, for example, the US military prevailed in the Mexican-American War, in 1848, many in Congress wanted to annex all of Mexico. In the end, the victor limited its spoils to the most northerly, least populated areas (including the current states of California, Nevada, and Utah) —“all the territory of value that we can get without taking the people,” as one newspaper editorialized. Or as John C. Calhoun, the pro-slavery senator from South Carolina, put it: “We have never dreamt of incorporating into our Union any but the Caucasian race.”

All the territory without the people. That, bluntly stated, was America’s preference, making the ninety-four uninhabited “guano islands” that the country began acquiring in the nineteenth century — for the express purpose of harvesting the bird droppings there for fertilizer — nearly ideal possessions. Populated territories required harsher measures. Immerwahr’s most shocking accounts concern the territories the US acquired in 1898 — the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam — after defeating Spain in what was dubbed the Spanish-American War, but which in fact began as a war of independence from Spain by those colonies. The Philippines in particular suffered deeply. Expecting independence after the Spanish were vanquished, this archipelago of more than seven thousand islands instead endured an American takeover that led to fourteen years of warfare, with more deaths than the Civil War, including the worst massacre by Americans in recorded history (the Battle of Bud Dajo, in which nearly one thousand Filipino Muslims were slaughtered). The country’s anguish, and American indifference to it, persisted into the mid-twentieth century: Immerwahr’s descriptions of how the Filipinos experienced World War II — caught between the Japanese occupiers and an American government much more focused on the war in Europe — are especially disturbing.

Puerto Rico, too, withstood one ordeal after another. The island’s uneasy relationship with the US mainland came into stark relief recently in the aftermath of 2017’s Hurricane Maria, but Immerwahr delves into earlier, uglier chapters, including a mind-blowing account of the deadly medical experiments performed on unwitting residents by Cornelius P. Rhoads, who went on to become a world-renowned cancer researcher. He also writes movingly about Pedro Albizu Campos, the Puerto Rican–born, Harvard-educated attorney who led a doomed fight for his homeland’s independence.

Immerwahr provides a riveting breakdown of the latest phase of American empire — the post–World War II era. With decolonization sweeping Africa and Asia, the optics of the world’s triumphant democracy holding on to its possessions would have been abysmal. So the four largest territories all got decolonized in some fashion: in 1946 the Philippines received its independence; in 1952 Puerto Rico was granted what Immerwahr calls the “nebulous status” of commonwealth; and in 1959, Alaska and Hawaii became states.

Since the mid-twentieth century, the name of the game has been “domination without annexation.” America has aspired toward a global hegemony built on technological prowess, linguistic supremacy, and increased military presence. In Immerwahr’s telling, the military has been particularly crucial to the enterprise. The US strategy of establishing foreign military bases (at least eight hundred by 2019) has replaced the necessity and expense of building actual colonies.

Regrettably, pursuing this highly militarized, “pointillistic” empire has had some dire consequences for the US. The most dramatic of these is probably al-Qaeda’s “planes operation” in 2001, better known stateside as 9/11. “Your forces occupy our countries; you spread your military bases throughout them,” Osama bin Laden wrote in his message to Americans after the attacks. While there were other grievances on his list, “September 11 was, in large part, retaliation against the United States for its empire of bases,” Immerwahr concludes as the reader’s heart sinks.

The US is routinely called out for its “original sins” of slavery and genocide (which Immerwahr duly notes). But as this essential book makes clear, there are many more sins yet to be reckoned with.