Madeleine Albright once famously asked General Colin Powell why he would not support sending US forces into the former Yugoslavia to halt Serbian atrocities. “What are you saving this superb military for, Colin,” Albright asked in exasperation, “if we can’t use it?”

Albright’s frustration was a response to the bloody ethnic violence that descended on the Balkans and also Rwanda in the early 1990s. As US ambassador to the United Nations and later as secretary of state, Albright ’68SIPA, ’76GSAS, ’95HON pushed hard for intervention against human-rights abusers, especially the Serbs. In 1999, she insisted that the Serbian military withdraw from Kosovo, even though the province was still internationally recognized as a part of a sovereign Serbia. When Serb leader Slobodan Miloševic´refused, Albright had NATO bombers ready to force his troops out.

At the time, Albright seemed to be responding to the chaos of the post–Cold War period. But her latest book reveals just how deep her commitment to resisting wicked regimes runs.

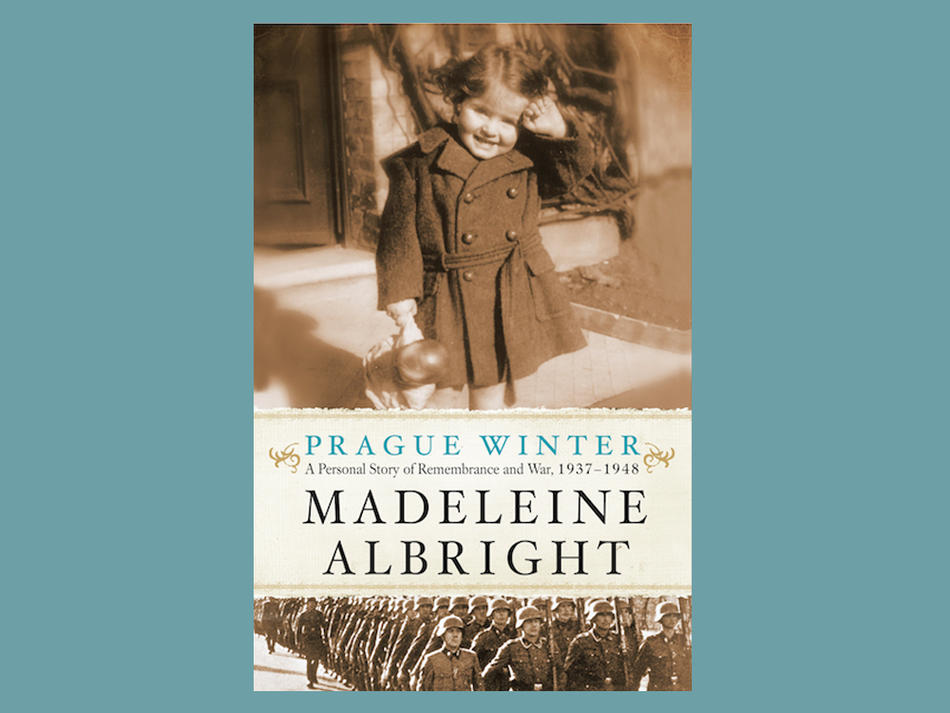

In Prague Winter: A Personal Story of Remembrance and War, 1937–1948, Albright may well have written the most poignant account we have in English of the tragic destruction of the so-called First Republic — the Czechoslovakia of interwar Europe — at the hands of Hitler and Stalin. Not much of this account is truly autobiographical: Albright was born only in the last years of the Republic’s existence and spent much of her childhood either in exile in London or with her diplomat father in postwar Yugoslavia. Like her contemporary, the future Czech president Václav Havel, Albright was too young to understand the larger forces undoing her country.

For contemporary reflections on the Republic’s fate, Albright turns to the letters, journals, and articles of her parents’ generation, especially those of her extraordinary father, Josef Korbel. This perspective allows Albright to infuse old political debates with the warmth of conversation at the family dinner table. Korbel and his contemporaries were not merely serving a historical state — they were building a home for their children. Albright portrays Korbel’s colleagues, especially Czechoslovak foreign minister and future president Eduard Beneš, in a detailed historical setting that feels as personal as a family photograph.

This intermingling of the familial and political gives Prague Winter unusual force as Albright discovers the true extent of her family’s suffering. Albright’s parents had raised her as a Roman Catholic; growing up she never knew that her parents had converted from Judaism or that dozens of her relatives had perished in Nazi camps. Albright did not even know that her own paternal grandfather had died at Terezín until the Washington Post explored her background in 1997.

Albright eventually discovered that while her parents were married in a civil ceremony and identified on their marriage certificate as bez vyznáni (“without religion”), they converted to Catholicism while in exile in England. Why, Albright wonders, did her parents convert then? They no longer needed fear the Nazis. Why convert once safely abroad?

Albright’s answer is utterly convincing, and also troubling. Working for a government in exile, she writes, the Korbels wanted to “underline our family’s identity as Czechoslovak democrats.” In the Czech political culture of the time, Jews were often disparaged as serving an international financial conspiracy or nostalgic for the Habsburg Empire. The Korbels’ concerns were quickly confirmed when a Czech group that had organized to resist the Nazis reported to London that they would be happy if the Jews who had fled stayed away.

Even a country as proudly humanitarian as the First Republic was not untainted by the ethnic prejudices that we associate with other Central European countries. The accommodations made to minorities could not disguise the fact that the First Republic was ultimately the fulfillment of the national aspirations of two nations: the Czech and, to a lesser extent, the Slovak peoples. The Czechs had built themselves a home, but Czechoslovakia’s roof stretched over peoples who had not been asked whether they wanted to move in.

This led to a bitter irony. Even the anti-Semites in the Czech resistance saw that the true threat to their country came from another minority, the country’s three million Germans, themselves centuries-long inhabitants of the territory. Many Sudetendeutsch welcomed their brethren from Germany proper when they marched in to dismantle the First Republic in 1938. This treason convinced the Czech leadership that any sizable German minority was now intolerable; at the first opportunity, the reconstituted government in Prague expelled nearly all of its Germans, regardless of individual innocence or guilt. Thousands were killed on the spot; thousands more died in transit. Millions lost their own ancestral homes.

Albright recognizes that innocent Germans were harmed in these purges, though she makes clear that her sympathies are with the Czech government. “Small countries can survive hostile neighbors,” she writes, “but the odds lengthen when a significant national minority identifies with the enemy.” This sentiment may well be of a piece with the tough-mindedness that Albright showed in protecting Kosovo’s Albanians from the Serbian army some fifty years later. But as Albright herself acknowledges, Havel and other Czech anti-Communists came to see the expulsions of Germans as a step down the path to totalitarian rule. No one, it turned out, could out-demagogue the Communists on questions of collective guilt: a party that could portray all the “bourgeoisie” as criminals could also portray every German as a national traitor. One can admire Albright’s excellent book and the moral urgency that she brought to US foreign policy. One can also recognize that the homeland she loves suffered when it did not live up to the ideals it was meant to embody.