The last miles of Caleb Daniloff’s first marathon were excruciating. Despite months of training, Daniloff wasn’t prepared for the physical and mental toll that the 26.2-mile course would take on him. But as he crossed the finish line, he knew he was ready to do it all again. Most marathoners wait a year before reattempting the full distance. Daniloff ’99SOA waited five weeks.

This kind of compulsion was natural to Daniloff, who was an alcoholic for fifteen years. He quit cold turkey when he was twenty-nine, but nine years later, at the start of the memoir, “the anxieties and insecurities I’d tried to cover up with booze still remained.” Marathon training proved the perfect stress-relieving, self-punishing, obsession-inducing hobby for his addictive personality. No one was surprised when h e signed up for a second race so quickly. As his wife said, “You can’t just eat one burrito, you have to have five hundred.”

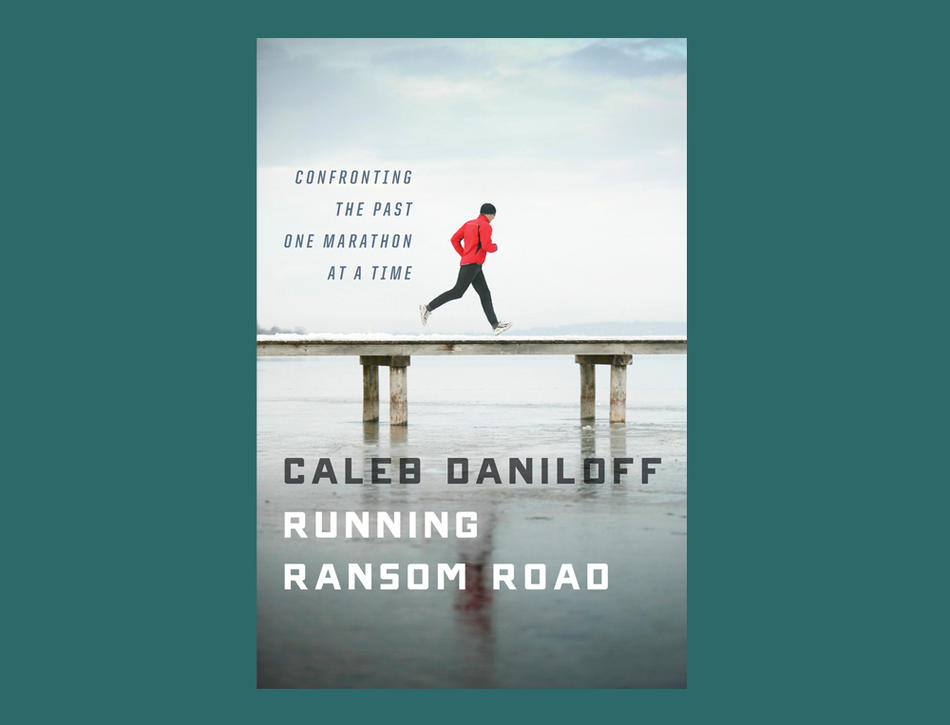

Runners and other endurance athletes will warm to the premise of Daniloff’s memoir, which follows him through five marathons in eighteen months, each in a location where he spent a portion of his life (Boston, New York, Burlington, rural Massachusetts, and Moscow) and each specifically designed to exorcise a set of demons from that period in his past. But running memoirs, even ones combined with tales of addiction or other hardship, are becoming commonplace, and non-running readers might find that the detailed race reports distract from the demons themselves, which are easily the most interesting part of his story.

Daniloff spent his teenage years, the incubator of his addiction, in Moscow, where his father, Nicholas Daniloff, was the Soviet bureau chief for U.S. News & World Report. The shy, awkward son was plunged into Soviet culture — Russian schools, competitive gymnastics, and a primitive pioneer camp — and easily adopted, too, the chain smoking and binge drinking that went along with them. Then, in 1986, when Daniloff was a surly sixteen-year-old, his father was detained by the KGB and jailed on espionage charges, making international headlines, causing the family’s deportation, and cementing Daniloff’s downfall.

Daniloff returns to Moscow in 2009 as a part of his whirlwind therapeutic running tour, and it is only here that the memoir truly feels distinctive and exciting. As the son of an important Cold War figure, a human embodiment of the massively complicated relationship between the two world powers, who came of age wanting only to assimilate into that enemy culture, he brings a fascinating perspective that, with an extended visit to the city, could have carried the whole book. As he watches businessmen crowd the now commercialized streets, he remembers arriving as a scared sixth-grader: “Moscow’s boulevards were festooned with red banners and images of Socialist leader Vladimir Lenin and Party Secretary Leonid Brezhnev. No pizza, no hamburgers, no Coke.” Moscow has soared beyond hamburgers and Coke, which Daniloff finds out when he meets his childhood friends Kolya and Kosh at an upscale sushi restaurant, but watching them battle with the vodka bottle, unemployment, and the same general malaise that had once afflicted much of his life, too, Daniloff recognizes his own progress: “I had reached some kind of mile marker I couldn’t see.”