In 1933, soon after Hitler came to power, the Nazis began expelling Jewish students and dismissing Jewish professors from their universities. On campuses across Germany, Nazis and their sympathizers publicly burned books written by Jews and other perceived enemies (including books by Columbia anthropologist Franz Boas).

Just months after the first book burnings, Columbia president Nicholas Murray Butler welcomed Hans Luther, the German ambassador to the United States, to Morningside Heights, insisting that he be accorded “the greatest courtesy and respect.” In Cambridge, Roscoe Pound, dean of the Harvard Law School, accepted an honorary degree from the University of Berlin. Returning from a 1934 trip to Germany, Pound told reporters, “there was no persecution of Jewish scholars or of Jews . . . who had lived in [Germany] for any length of time.”

As Stephen H. Norwood ’84GSAS forcefully demonstrates in The Third Reich in the Ivory Tower: Complicity and Conflict on American Campuses, some of America’s top universities adopted a hear-no-evil attitude toward Hitler’s Germany that bordered on complicity.

Columbia was one of the few places where that attitude was challenged. The editors of the Daily Spectator reacted strongly to what was happening in Europe. In the aftermath of the expulsion in 1933 of 15 Jews from university faculty positions in Germany, the newspaper called on Butler to hire them as Columbia professors. Later, in an editorial titled “Silence Gives Consent, Dr. Butler,” the Spectator bitterly denounced what it saw as Butler’s courtship of the German government and its universities. In yet another, the newspaper wrote, “The reputation of this University has suffered . . . because of the remarkable silence of its President . . . ”

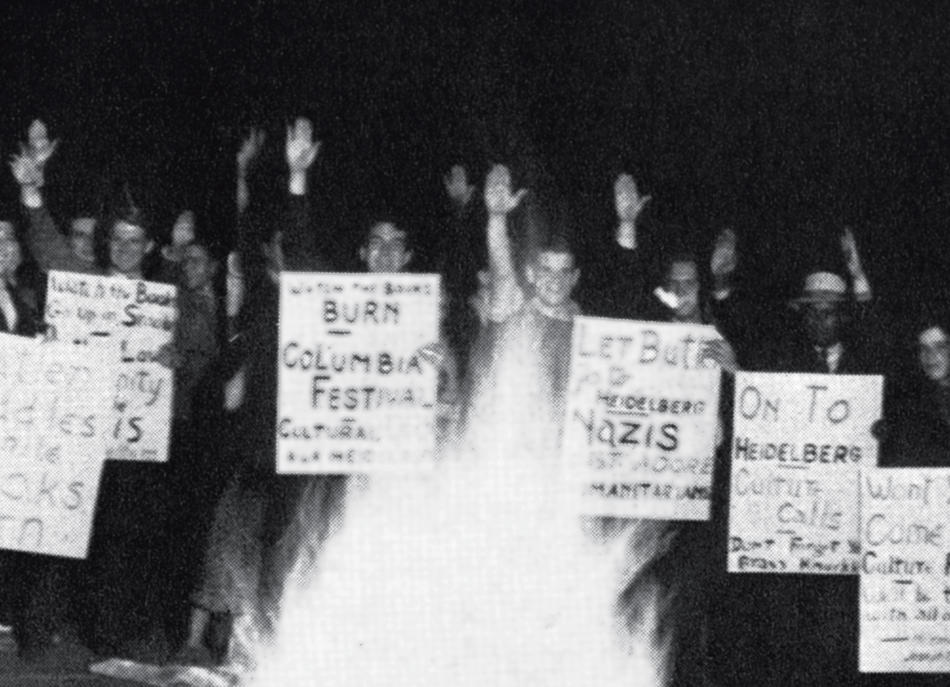

Butler responded to criticism from the Spectator and other student groups by emphasizing that Columbia’s relationships with German universities were “strictly academic” and had “no political implications of any kind.” He went on to mock the protests. “We may next expect to be told that we must not read Goethe’s Faust, or hear Wagner’s Lohengrin, or visit the great picture galleries at Dresden, or study Kant’s Kritik, because we so heartily disapprove of the present form of government in Germany.” Butler, who was “a longtime admirer of Benito Mussolini,” wasn’t exactly apolitical, though. In 1934 he fired Jerome Klein ’25CC, ’32GSAS, a promising young member of the fine arts faculty, for signing an appeal against the Luther invitation; and he expelled Robert Burke, a Columbia College student, for participating in a 1936 mock book burning and anti-Nazi picket on campus.

Butler was far from alone in his admiration for Germany and in his distaste for those who would allege that it had a sinister side. The Harvard Crimson, writes Norwood, was an apologist for the German regime and repeatedly belittled protest efforts against it. After a huge Jewish-sponsored anti-Nazi rally was held in Madison Square Garden in March 1933, the Crimson opined that the rally “proved nothing” since Hitler had not been provided with a defense. “Moreover,” Norwood reports, the Crimson “claimed that the audience, containing many Jews, was ‘rabidly prejudiced.’”

The Harvard case was particularly disturbing, most infamously because of the warm welcome extended to alumnus Ernst Hanfstaengl at the 1934 commencement and reunion. Hanfstaengl was a Nazi leader and close friend of Hitler. While much of the national press was appalled, most of the Harvard community was delighted. “It is truly shameful,” writes Norwood, “that the administration, alumni, and student leaders of America’s most prominent university, who were in a position to influence American opinion at a critical time, remained indifferent to Germany’s terrorist campaign against the Jews and instead, on many occasions, assisted the Nazis in their efforts to gain acceptance in the West.”

Norwood, a professor of history at the University of Oklahoma, reveals how widespread this attitude was among administrators, professors, and students at some of America’s elite universities, who not only argued that academic life should be free of political considerations, but actually supported the Nazi regime. Aside from Harvard and Columbia, Norwood deals with several other colleges and universities, including the Seven Sisters, several Catholic universities, and the University of Virginia. What makes his book all the more chilling is his documentation showing that from the earliest days of Hitler’s reign, there was no shortage of people who seemed to notice what was going on: American and British newspaper reporters, political figures, Jewish leaders, and refugees, who offered firsthand testimony.

Meanwhile, he writes, “American universities maintained amicable relations with the Third Reich, sending their students to study at Nazified universities while welcoming Nazi exchange students to their own campuses.” In so doing, he concludes, “they helped Nazi Germany present itself to the American public as a civilized nation, unfairly maligned in the press.”

One minor flaw in Norwood’s book is that he lumps together sins of omission and commission. For example, he writes that university presidents did not urge their students to attend the 1933 Madison Square Garden rallies or other protests. Later, he writes that they “showed no interest” in the nationwide boycott of German goods. The sins of commission are much more convincing in building his case.

The record of the younger generation is more encouraging. Though students of the early 20th century had been conditioned to be complacent and go along with the wishes of the administration, the angry resistance of many Columbians during this period was unlike anything seen before on American campuses. In some ways, the student reaction to Columbia’s entanglement with the Third Reich in the 1930s foreshadowed what would happen a generation later when students challenged their university administrations over such issues as the war in Vietnam and civil rights. The 1930s was a more volatile and engaged time for students than most of us may have realized, and Norwood does us a special service by revisiting it in this book.