In the course of the past four decades, Robert Dallek ’64GSAS has produced a succession of pathbreaking historical studies of the foreign policies of American presidents, from Franklin D. Roosevelt to Richard Nixon. His earlier works were based on extensive research in the primary-source collections of presidential libraries and government archives. They unearthed striking new information of great interest to professional historians and the general public. In An Unfinished Life, his biography of John F. Kennedy, for example, he presents a wealth of new information about Kennedy’s severe health problems gleaned from the previously unavailable medical files kept by JFK’s personal physician.

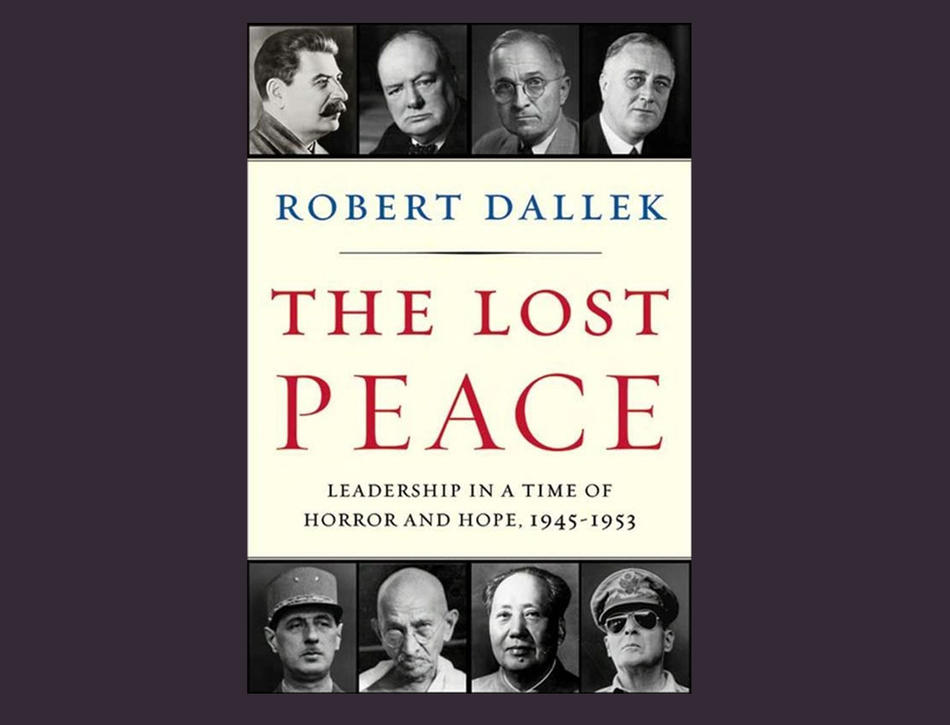

His latest book, The Lost Peace: Leadership in a Time of Horror and Hope, 1945–1953, does not pretend to reveal long-hidden secrets of statecraft. It is based exclusively on secondary sources and is dominated by a single interpretive theme that is foreshadowed in the book’s title. In investigating the foreign policies of the major powers in the world during what might be called the Truman-Stalin era, he poses a simple question: “Why can’t a world with so many intelligent and thoughtful people do better?” Dallek laments the irrational, unrealistic actions of world leaders that were fueled both by highly distorted interpretations of historical precedents and by an egregious misreading of contemporary developments in the years after World War II. In highlighting several instances of such flawed leadership, he wistfully asserts that a heavy dose of rational, realistic analysis in the early stages of the Cold War would have resulted in a much more stable and peaceful international order than the one produced by statesmen (and they were all men) at critical turning points in world history after the breakup of the Grand Alliance in 1945.

This elegantly written book does not stop at identifying the many instances of what the author regards as woefully mistaken decisions. It takes the next step of proposing alternative policies that might have resulted in a much safer and more secure world than the one bequeathed by the architects of the Cold War. One can assign Dallek’s book to the genre of counterfactual history, which considers the what-ifs of the past. “Ultimately, one of the great tragedies of World War II after the death of so many millions,” he mordantly observes, is that “it became not an object lesson in how devastating modern weaponry had made wars of any kind . . . but the foundation for military buildups by America and Russia, the two greatest victors in the conflict.”

If only Truman had pressed for a new summit meeting with Stalin after the atomic bombardment of Japan to express America’s reluctance to build such destructive weapons in the future and to invite the Soviets “to join him in a shared effort to ban their development and deployment.” If only Stalin had explicitly expressed his genuine fears of a German revival, and had promised self-determination for the countries in Eastern Europe that his armies had liberated in exchange for “a [U.S.] commitment to Germany’s permanent demilitarization, the march toward East-West conflict might have been averted.”

If Truman had recognized “that China’s Communists might be willing to stand apart from Moscow” and were amenable to improving relations with the United States, Washington could have “abandoned Chiang for Mao and his transparently more popular party” during the Chinese Civil War, which reached its turning point in the years after the Second World War. The long period of Sino-American hostility might well have been prevented.

Turning his attention to postwar developments in the Middle East, Dallek wonders why “no one seemed to think of annexing a part of Germany comparable in size to the small area of Palestine to make up the new state of Israel . . . A Jewish state in Europe, where most of the settlers in the new homeland had been born, could have avoided the bloodshed” between Israelis and Arabs in subsequent years caused by the “displacement” of Palestinians. In fact, someone did propose the carving out of a homeland in Germany for the survivors of the Holocaust. King Abdul Aziz Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia made just such a suggestion to Roosevelt during their secret meeting aboard a U.S. naval vessel in Egyptian waters on February 14, 1945, during FDR’s return trip from the Yalta Conference. It is hard to imagine that such a solution would have been palatable to the destitute Jews crowded into displaced-persons camps in Europe. One presumes that they had no interest in remaining in a country that had maltreated them so horribly during the war, but, rather, longed to reach the state that their coreligionists in Palestine already were preparing to create after the end of the British Mandate.

A recurrent theme of the book is the periodic misreading of history and the development of false historical analogies that yielded unsound policies. Memories of appeasement and American isolationism in the 1930s, coupled with the tendency on the part of many American leaders to equate Stalin with Hitler, foreclosed the kind of sober, realistic appraisal of Soviet intentions that could have produced a more stable and peaceful world. Dallek notes that such missteps and false historical analogies were not confined to Washington. “One can only imagine how much better off Russia and the world would have been if . . . the unyielding ideologues in the Kremlin” had realized that a “cooperative posture” toward Washington would have been welcomed in the United States and yielded American economic aid to that devastated country.

The lone hero amid Dallek’s long list of villains in this unfolding drama was George Kennan, whose ideas “might have changed the course of the Cold War” if they had been taken seriously by U.S. policymakers. Had his expressions of concern about the excessive and unrealistic aspirations incorporated in the Truman Doctrine and the militarization of the containment policy symbolized by the formation of NATO been given serious consideration in the Truman administration, the costly and dangerous nuclear arms race between the two superpowers could have been avoided. The kind of clear-eyed, coldly realistic analysis that Kennan brought to bear on world events was notably absent in both Washington and Moscow, whose leaders, Dallek believes, allowed their personal prejudices and misreading of history to distort their vision of the world.

As Dallek sees it, the Korean War “was the result of poor leadership and misjudgments” by the leaders of all the interested parties: South Korea’s strongman Syngman Rhee’s bellicose statements calling for the unification of the peninsula under his rule; Truman’s and Dean Acheson’s failure to explicitly warn the North that an armed attack on the South to achieve unification under Pyongyang’s rule would be met with an American military response; Washington’s passivity in the face of MacArthur’s insistence on crossing the 38th Parallel and toppling the North Korean regime; Mao’s dragging his heels on the possibility of a negotiated settlement, despite the almost 1 million Chinese casualties in the war, over the subsidiary issue of prisoner-of-war exchanges; Stalin’s grossly mistaken belief that by tying down the Americans in a long, drawn-out conflict in East Asia, he would prevent them from building up military forces in the region that most concerned him — Europe.

Like all counterfactual history, Dallek’s lucidly presented and powerfully argued indictment of these postwar world leaders is vulnerable to the popular complaint that hindsight is 20/20.Retrospective criticism of decision making, fortified by the knowledge of what in fact transpired after the events in question, fails to take into account the limited information that leaders at the time possessed, the difficult choices they faced, and the trying circumstances under which they had to operate. The alternative scenarios that Dallek indulges in are intriguing, even if some are implausible: Soviet-American cooperation in the prevention of a nuclear arms race and the creation of a neutralized, disarmed Germany in Europe; a postwar Jewish state in the Rhineland rather than in Palestine; the replacement of Chiang with Mao as Washington’s partner in Asia; and a Soviet withdrawal from Eastern Europe, followed by an American program of economic assistance to its war-ravaged former ally. Leaving aside the question of whether these alternatives would have been preferable to what really happened, we need to ask if they were even remotely possible in the critically important transitional period from world war to cold war.