When Random House sent Robert Moses a review copy of Jane Jacobs’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities in 1961, New York’s master builder was predictably infuriated. Jacobs declared war from the very first sentence: “This book is an attack on current city planning and rebuilding.“ An attack, in other words, on Moses’s record, which would ultimately include the construction of 13 bridges, the Cross Bronx and Long Island expressways, 658 playgrounds, 2 tunnels, 17 state parks, plus Lincoln Center and the United Nations.

Moses ’14GSAS, ’52HON returned the copy, advising Random House to “sell this junk to someone else.“ But to his consternation, Jacobs’s work became one of the most influential books ever written about American cities and how they function. A Greenwich Village mother and activist, she deplored the human cost of urban renewal and denounced Moses’s replacement of lively neighborhoods with skyscrapers, housing projects, and highways. Jacobs celebrated the everyday magic of the American city, praising communities where different classes mingled and storefronts shared space with apartments. From her second-story window at 555 Hudson Street, she marveled at “the ballet of the good city sidewalk,“ and her crusade to preserve, rather than simply demolish, older buildings was embraced by a new generation of planners beginning in the 1960s.

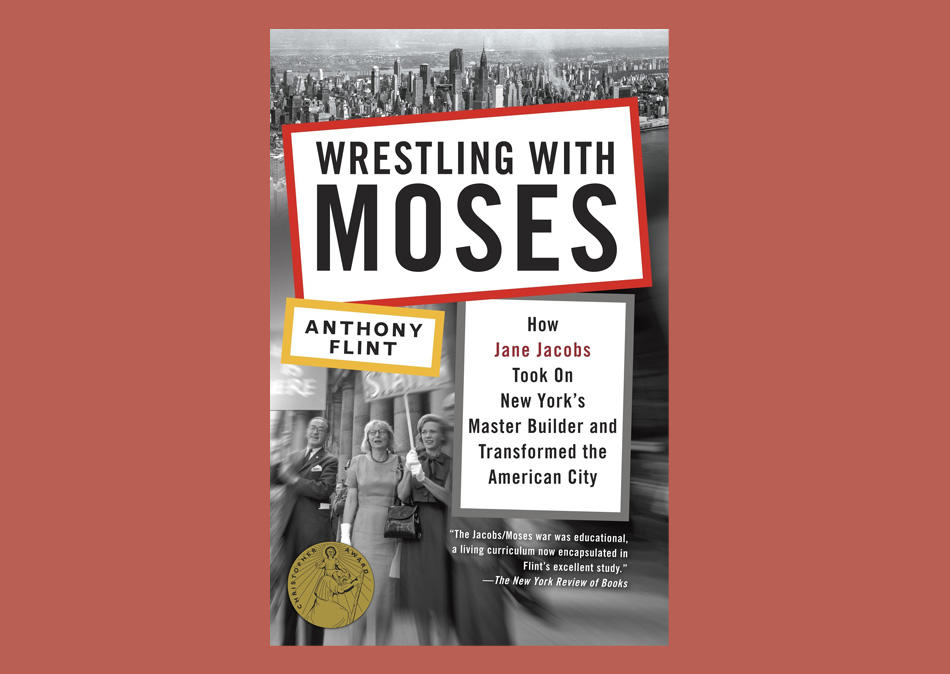

The story of Moses and his impact was told in the classic 1974 portrait, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York, by Robert Caro ’67JRN. Far less has been written about Jacobs’s life and her battles against the über-planner’s projects, most notably, a planned expressway through Lower Manhattan. Anthony Flint’s Wrestling with Moses: How Jane Jacobs Took on New York’s Master Builder and Transformed the American City attempts to fill this gap, and for the most part succeeds admirably. Flint ’85JRN, a former reporter for the Boston Globe, chronicles the clashes between Jacobs and Moses as they began locking horns in the early 1950s. The two never met. But their David and Goliath confrontations — she as a grassroots organizer, he as the city’s most powerful planner — sparked angry battles over the future of Washington Square Park, the streets of Greenwich Village, and the congested, densely populated communities of Lower Manhattan.

Flint’s narrative ends when both players left the stage in 1968. Moses, who had enjoyed support from politicians going back to Al Smith in 1918, was stripped of his powers by Governor Nelson Rockefeller. Jacobs, her husband, and their two sons, driven by her opposition to the Vietnam War and the draft, moved to Toronto. More than 40 years later, Flint writes, “the business of development has changed completely as a result of Jacobs’s work. Builders and local government officials alike defer to the concerns of the neighborhood, involving the community in every step of the process. . . . They live in fear of riding roughshod over citizens.“

The book charts Jacobs’s emergence as a journalist with Architectural Forum and an activist, focusing initially on her protests against Moses’s plans for an extension of Fifth Avenue through Washington Square. Long before it became common, she and her grassroots allies mastered the art of working with the media; they cultivated such rising politicians as Edward I. Koch and John V. Lindsay. They also learned the value of deploying children in battles with City Hall. Once, when Jacobs was buying long underwear for her boys, a clerk asked her if it was for the winter. “No,“ she said. “It’s for picketing.“

Flint’s crisp, entertaining prose contrasts Jacobs’s passion for Washington Square’s bohemian flair with Moses’s button-down disapproval. To Moses, Flint writes, the park “needed a shave and a haircut, and to find a steady job. It needed to knock it off with the poetry readings and start serving a practical function for the city again.“ When Flint describes the fierce citizen army that sprang up to defend the square, in essence he describes the birth of modern community protest politics, including tactics that would inspire “freeway revolts“ in other cities. These strategies are now routinely employed by organizers from coast to coast, and Moses’s famous complaint that the only people who opposed him were “a bunch of mothers“ seems almost poignant in retrospect.

Wrestling with Moses suffers in its parallel approach to these twin characters. Flint provides a wealth of little-known material about Jacobs. Yet no matter how thorough he is in summarizing Moses’s career, Flint’s work on Moses comes off as second-best compared to Caro’s blockbuster. More important, Flint describes but does not fully explore a revisionist school of thought that is more sympathetic to the builder. Indeed, the author’s comment that Moses’s “entire career, built on energy, ambition, single-minded pursuit of power has been repudiated“ may strike some as excessive, given the 2007 exhibitions, lectures, and publication of Robert Moses and the Modern City: The Transformation of New York — the work of Columbia historian Kenneth T. Jackson and his former colleague Hilary Ballon — that tried to balance the historical scales. Jackson praised Moses as a man who, despite autocratic flaws, changed the city and embodied a can-do ethic. With New York lurching through the rebuilding of ground zero, some openly voice nostalgia for a planner who knew how to get things done.

Flint does acknowledge that some of the ideas in The Death and Life of Great American Cities would eventually collide with other priorities. The push to preserve older neighborhoods, for example, had the unintended effect of blocking construction of much badly needed housing across the country. It also encouraged a gentrification that would have been the last thing on Jacobs’s mind. On the day after she died in 2006, someone left flowers and an anonymous note at the door of the building where she had lived: “From this house, in 1961, a housewife changed the world.“

There have, in fact, been many changes at 555 Hudson Street: When Jacobs and her husband bought their three-story walk-up in 1947, it cost them $7000. Recently, it sold for $3.3 million.