Late on a winter afternoon, in the ground-floor studios of the Upper East Side carriage house where Jacob Collins ’86CC runs the Water Street Atelier, it is easy to imagine that time stopped more than a century ago. Dozens of plaster casts of Greek and Roman busts, friezes, and torsos line the walls. A few are set up under lights to be drawn, and in a nearby grove of heavy old wooden easels, a half dozen students quietly work at shaded graphite renderings. Paintings line the high walls — portraits, nudes, and landscapes that look nearly as old as the casts. Music by Verdi coming from speakers somewhere unseen provides the perfect soundtrack for time travel.

Water Street is the first of three art schools Collins has founded in New York City, and it has been in operation for more than 15 years (the name is a holdover from an earlier incarnation in Brooklyn). A proponent of a style that has come to be called classical realism, Collins is also the founding director of the Grand Central Academy, which opened last fall, and this summer he will inaugurate the Hudson River School for Landscape. The latter will be affiliated with the Sugar Maples Center for Arts and Education, a school in the Catskill Mountains a stone’s throw from the vistas that inspired such original Hudson River School painters as Frederic Edwin Church and Thomas Cole.

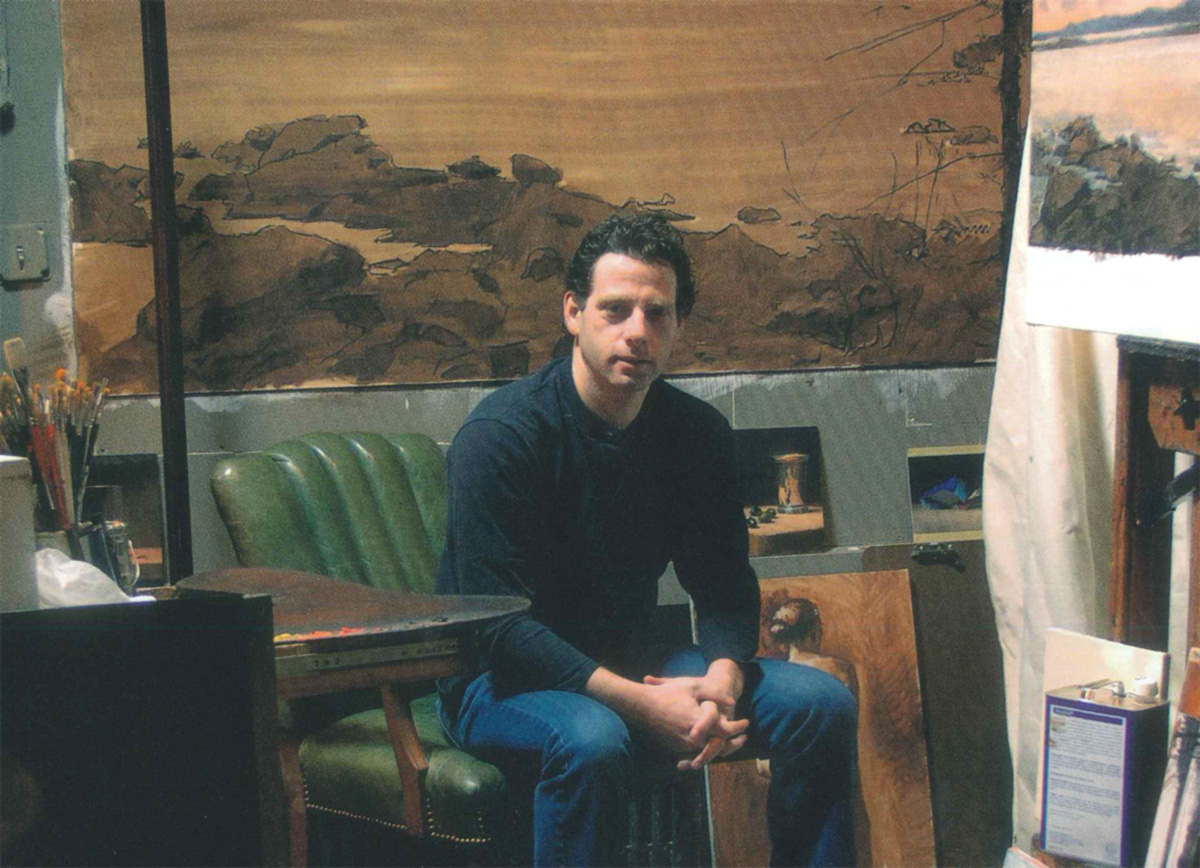

Collins, 42, comes downstairs from the apartment where he lives with his wife, Ann Brashares ’89BC, author of the wildly successful Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants books for preteen girls, and their three children. Leading the way to the rear of the atelier, Collins pushes aside fraying lengths of brocade fabric stapled across the doorway to a second studio, a large, square space illumined by a skylight. Again, paintings are everywhere, including one of Brashares as the Mona Lisa. In Collins’s world, none of the shimmering inexactitudes of impressionism mar the dusky shadows, and certainly none of the sweeping gestures of 20th-century abstraction disturb the almost preternatural tranquillity.

The spell is finally broken when Collins’s cell phone rings and he excuses himself to answer it. A friendly black Lab lopes in and out, and one of the children, Sam, 11, shoots through the curtains from time to time, as if on wheels, and stays to chat a bit. The carriage house was featured in a recent article in the New York Times headlined “Art Above and Below, With Life in the Middle,” but life is clearly welcome on all floors.

Dressed in jeans and a plaid flannel shirt, Collins looks contemporary and therefore strangely out of place in his own studio, where a work in progress shows a little girl in a full-skirted dress that would have been à la mode in 1900. Collins has nothing against painters being modern, but he chafes at the idea that it might be mandatory. “If a person wants to be contemporary, that’s OK,” he says, “but there was a time when I realized that I didn’t have to be painting a Pontiac or the space shuttle. In Michelangelo, for example, you wouldn’t see what 15th-century Florentines wore, or their little technological appurtenances.”

Rejecting Rejection

While at Columbia, where he majored in history, Collins began to realize that wrestling with the art of his own time (which would still have included conceptual art, photo-realism, and minimalism) was something he was not going to do. “The underlying premise of art for the last 140 years has been the rejection of traditional values, in one way or another,” he says. “In a way, I just sort of stepped out of that world, and I’m still out of it. But now the art world has just broken wide open. There is a wonderful bursting world of neoclassical, traditional painters who look at Jean-Auguste-Dominque Ingres, John Singer Sargent, Church, all these 19th-century and 18th-century painters. And we’re flying along, and selling our work, and teaching our students, and building our relationships with each other.”

In December, Collins had his second exhibition at Hirschl & Adler Modern, a gallery whose stable once included abstractionists but now consists mainly of realists. Roger Kimball, managing editor of the New Criterion and author of The Rape of the Masters: How Political Correctness Sabotages Art, wrote the catalogue essay, in which he predicted that Collins’s paintings and drawings some day will be seen as “that climacteric when the recovery of American art…finally began to take root.”

It is an art-world cliché to decry lost standards. In 1962, art historian Leo Steinberg wrote an influential article called “Contemporary Art and the Plight of Its Public,” in which he eloquently evoked the “sense of loss” that accompanies the shock of the new — “a feeling that one’s accumulated culture or experience is hopelessly devalued, leaving one exposed to spiritual destitution.” Contemporary art, he wrote, “is constantly inviting us to applaud the destruction of values which we still cherish.” Rather than point the finger at academics, as had routinely been done in the past, Steinberg cited artists’ reactions to challenging new works — Henri Matisse’s view of Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) as an “outrage,” Signac’s certainty that Matisse had “gone to the dogs” when he painted The Joy of Life (1906) — and then proposed that anyone “becomes academic by virtue of, or with respect to, what he rejects.”

The difference between 1962 and now is that, at least for artists like Collins, the term academic is no longer considered an epithet. Collins happily admits to admiring such 19th-century Beaux-Arts painters as William Bouguereau, whose allegories met with disdainful snickers (or just collected dust) throughout most of the 20th century. Even among conservative critics, however, there is uncertainty that classical realism is the answer to the art world’s prayers. In a New Criterion article titled “The New Old School,” James Panero ended on a cautionary note: “Just as certain forms of modernism have become a perversion of taste, my hope is that classical realism does not become that unrelenting embrace of tradition, with similarly dire results.” Maureen Mullarkey, in the New York Sun, referred to classical realism as “a contemporary style with retro appeal — like Chrysler’s PT Cruiser” and called Collins’s nudes “fastidious erotica to go with the Jado bidet and high-thread-count linens from Yves Delorme.” They are “less a counter to the vacancy of contemporary culture than an extension of it.”

Kimball, on the other hand, sees classical realism as a savior from “previous pathologies,” a phrase that from his pen could include a multitude of affronts, from the audacities of the Dadaists to postmodern art theory. And Panero calls classical realism a “value system,” rather than simply a style: “For many, it borders on an evangelical faith.” Mullarkey calls Collins “the Ralph Reed of a secular revival culture built on the gospel of traditional art practices.”

While Collins is an unabashed advocate for rigorous classical training, he seems too relaxed and sophisticated to proselytize, and he eschews negativity. “I don’t really want to advertise myself as disaffected,” he says. “It’s not that I didn’t like modernism, but I loved extraordinary draftsmanship. I looked at Hans Holbein and Raphael and Michelangelo, and that’s what I wanted to do so much. If it doesn’t have that classical, underlying, structured draftsmanship, it’s just not what I’m interested in.” He respects some 20th-century painters, especially the abstract expressionists, whose sense of the transformative power of art is close to his own, but “that doesn’t mean that I care about them very much. What happened after that — the irony of postmodernism — is just ridiculous. I don’t care about it at all.

“I always wanted to do two things: to be skillful and to make beautiful art,” he says. “I never had any confusion. Not that I am so skillful. I’ve been looking at Holbein drawings, Diego Velásquez portraits, and ancient Greek sculptures my whole cogent life, and you can’t look at those things and really feel good about yourself. The other thing that interests me is to make things beautiful. Often, when you’re in art school you get people saying, ‘Sure, this is pretty, but let me see what your ideas are.’ When I was a kid I didn’t know why that bothered me, but later I realized that it’s based upon the fallacy that beauty isn’t an idea. Beauty is a set of ideas, it is vastly complicated, and to understand whether something is beautiful, you’re using anthropology and psychology, and culture and nature, and even biology. You have to understand what ‘beauty’ is to know why you think something is beautiful.”

Old-World Star

In the world of classical realism, Collins is a star, and he is one of a very few whose paintings may make the leap from the relatively small world of realist artists, galleries, and magazines to mainstream venues where various ideas and styles collide. Prices for his work are substantial: His small pieces can be acquired for around $5000, but his large paintings have sold for as much as $100,000. One of his commissions was for a portrait of the first president Bush.

Looking at his work, it is easy to see why he stands out. His nudes, especially, reveal a point of view that is distinctly contemporary. Whereas many contemporary classical figures can seem stiff, stale, pained, or mysteriously allegorical, Collins’s seem to breathe the same air that the viewer does. And although his setups are simple, incorporating at most a bed sheet and a length of an elegant fabric, they are oddly compatible with 21st-century exhibitionism and voyeurism. There have always been luscious paintings of nudes — Peter Paul Rubens and Velásquez made drawings and paintings that celebrated flesh. Amedeo Modigliani, Egon Schiele, Picasso, and uncounted others continued that tradition in the 20th century. Perhaps because of Collins’s reverence for the Old Masters, however, viewers are sometimes surprised to be confronted with a painting like Reclining Nude (2006), which shows a supine model with one leg swung wide and recalls Gustave Courbet’s Origin of the World (1866), a smallish depiction of a largish vagina.

There are aspects of the painting that a classical painter might avoid. Collins sometimes chooses to foreshorten both halves of a protruding limb — in this case, a leg — which Renaissance draftsmen advised against, to avoid a sausagelike effect. And the model, while painted with thoroughgoing clarity, is laid out like a landscape — Earth? Or, remembering Courbet, Earth Mother? Collins manages this human horizon by working from a point of view almost at the level of the mattress, or platform, on which the model lies. It is as if the viewer is on his knees, before an altar or a shrine, in the end entirely reverent. Reclining Nude is erotic, but it also reminds us that Eros is a life force, the god of love, the instinct for self-preservation, and not sexual desire alone.

Collins chooses to work in a format that is small by contemporary standards. Only one of the canvases in his last exhibition measured more than four feet in one dimension. In Reclining Nude, for example, as in many of Collins’s works, the model is painted half-size, which significantly reduces her impact on the viewer. In some paintings that show just a part of the figure, the model is painted life-size. Carolina (2006) is a nude bust of a young woman seen from a point just behind her left shoulder. She turns to look back, but stops partway, her gaze falling on a point low to her left, as if she has heard a sound. Her eyes seem empty, except for a flicker of mild interest or irritation. She is darkly pretty, but at the same time completely ordinary — the girl on line in front of you at the bodega. Collins has caught the slight difficulty of her pose — the effort she makes to hold her head to one side and keep her back straight. Her breast is a point of interest. Collins makes it the palest, most luminous focal area in this 22-x-20–inch painting. And yet despite its magnetism, in the end it is the model’s youthful face that haunts the viewer’s memory.

Brave New World

Interest in realism never entirely died out. It has burgeoned since the early 1980s, when artists like Avigdor Arikha, Rodrigo Moynihan, and Antonio López Garcia were exhibiting abroad, and Andrew Wyeth, William Bailey, and Lennart Anderson were receiving positive critical attention in the U.S. But no artist or movement of the time had one foot planted in the 19th century, as Collins does. “People like Bailey and Anderson go back through the New York School,” he points out, “which was the only thing I knew about as a child. It was my parents’ world.” (See sidebar.)

At the time, Collins believed that the body of knowledge of classical art techniques had disappeared, so he began to cobble together a formal art education on his own. There was nothing then like the Water Street Atelier. “This world, this neo-academic revival of the classical values of drawing and painting, was just finding its feet when I was graduating from Columbia.”

The New York Academy, a school devoted to the figure, had opened in 1985. Collins studied there for a year and then discovered a teacher at the Art Students League, Ted Seth Jacobs, a painter who studied with an illustrator and landscape painter named Frank Vincent DuMond, who had trained in the 1890s. “When you change gears and step out of a world whose parameters have been defined by Clement Greenberg [the formalist critic], you see a whole lot of other stuff,” Collins says. “That’s what happened to me.”

On the other side of the looking glass, Collins gradually created the world he had been seeking, beginning in the Water Street Atelier. “When I was starting to teach, I got some really spectacular students who were really not so different in age from me, and I got a lot of reverse teaching, in which I was the beneficiary.”

Homage à Trois

One study in Collins’s studio is for a commissioned portrait of two children, the younger one sitting on the floor in the instantly recognizable pose of the youngest girl in Sargent’s The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit (1882), recently seen in the Americans in Paris: 1860–1900 exhibition at the Metropolitan. At this early point, Collins’s painting is mostly vacant, apart from the suggestion of two figures in a deep umber wash that covers most of the canvas. Sargent’s famous quadruple portrait shows four girls in the cavernous, shadowy foyer of their Paris apartment. A contemporary critic called the painting “four corners and a void,” and several since have remarked on its aura of loneliness, suggesting that it was Sargent’s comment on expatriate life. Sargent’s source, in turn, was Velásquez’s Maids of Honor (1656), which is, in its way, also about the condition of the outsider. As Jonathan Brown and Carmen Garrido point out in Velázquez: The Technique of Genius, Velásquez aspired to the noble status of artist, which was granted to poets, for example, but denied to painters, who were regarded as mere craftsmen.

Collins doesn’t know why he was able to resist the forces around him and commit himself single-mindedly to reaching his goals, but he was never distracted by other paths. “In a lot of ways I’m a very simple person,” Collins says, “and I think that’s maybe a valuable trait. Woven into my work is a love for a particular group of painters, and a willingness to submit to a reverence for that world. That could easily lead a person to become slavish, to lose his or her own voice, but I think in my case it is my voice. I love those artists, and I want to be one of those artists, to speak very directly in the language that I’ve spent my whole life trying to learn.”

Related by Degrees

Collins is the scion of a remarkable family, one whose ties to the art world and to Columbia and Barnard are equally notable. His maternal great-uncle was the renowned art historian Meyer Schapiro ’24CC, ’35GSAS, ’75HON, who graduated from Columbia at 20, began teaching here even before finishing his dissertation, and introduced the study of art history to the Core Curriculum. Schapiro, also a painter, was as interested in the art of his own time as he was in Romanesque architecture, his art-historical specialty. His lectures on modern art at the New School in the 1940s were a touchstone for young American painters in the city, most of whom had never traveled to Europe or seen a Picasso painting in the flesh. Collins’s maternal grandmother, Alma Schapiro, studied with Hans Hofmann, the famous modernist teacher whose “push-pull” theory of the picture plane affected generations of abstractionists.

Collins’s grandfather, Morris Schapiro ’23CC, ’25SEAS, Meyer’s older brother, was a 1911 graduate of what is now The Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science. Some small part of the millions of dollars he donated to Columbia now helps to finance the Meyer Schapiro Professorship of Modern Art and Theory, occupied until recently by Rosalind Krauss, now a University Professor, whose interest in such thinkers as Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Jacques Lacan, Jacques Derrida, and Roland Barthes places her at a distant remove from the world of the classical realists.

Collins’s older brother is actor Rufus Collins ’84CC. Their mother, writer Linda Collins, is a 1952 Barnard graduate.

Collins met Ann Brashares in the Philosophy Reading Room at Butler Library when she was a Barnard student. He fell immediately in love and surreptitiously drew her portrait, studying her from across the room. “We’ve been hanging out ever since,” he says. She was studying, too, for a freshman course taught by his father, philosophy professor Arthur Collins ’56CC, ’59GSAS.