● Most days there’s a moment in my commute when I look up and imagine somebody walking onto the subway train with an AR-15. I don’t suppose other people think about this stuff as much as I do, but I can’t avoid it: guns have crept into my consciousness.

● I work at the Trace, a nonprofit, nonpartisan newsroom that focuses on America’s gun-violence epidemic. This makes me an informed reciter of grim statistics: these include more than three hundred mass shootings in the past year. Seventeen dead and seventeen injured at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. Ten dead and thirteen injured at Santa Fe High School, near Houston. Eleven dead and six injured at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh. Twelve dead and twenty-one injured at the Borderline Bar and Grill in Thousand Oaks, California.

● These numbers are incomplete. Beyond the mass shootings that make the headlines, there is no true, real-time accounting of who is getting shot every day — in bar fights, suicides, accidents, “crimes of passion,” gang killings, and drive-bys. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention keeps statistics on gun fatalities culled from death certificates, but their figures are two years old. (There were thirty-eight thousand gun-related fatalities in 2016.)

● And lost in the stats are the physical and psychological wounds of gun violence. Tens of thousands of people are shot each year, and often their injuries are devastating: shattered bones, perforated organs, and spinal-cord and brain injuries. The psychological toll is, of course, all but impossible to calculate.

● I started covering gun violence nearly six years ago, in the wake of the attack by a lone gunman at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut. I was an editorial assistant at the New York Times, working for business columnist Joe Nocera. Joe had a young child, and the slaughter of twenty first-graders and six educators in their classrooms hit him hard. As a father, he wanted to know how this could have happened. As a reporter, he needed to understand the scale, scope, and impact of gun violence in America. He asked me to find out more.

Since no government agency aggregates this data, I resorted to daily Google News searches and wrote a few lines about every incident in a blog Joe called The Gun Report. I usually documented about twenty a day, five days a week. It was by no means comprehensive: we were missing a lot more incidents than we found. Still, for a year and a half I devoted most of my life to the endless cataloging of gun injuries and deaths in the US. The conclusion that emerged from this work was not surprising. In fact, it was radically simple. As Joe wrote just a year into the project, “The clearest message The Gun Report sends is the most obvious. Guns make killing way too easy.”

● The Trace, the country’s only digital news site covering gun issues 24/7, was launched in 2015. I was one of the first staffers. Launched with grant funding from Everytown for Gun Safety, a nonprofit established after Sandy Hook to advocate for gun reform, The Trace was supposed to go live toward the end of June, but we had to bump up the date because on June 17, 2015, a twenty-one-year-old white supremacist murdered nine people at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina.

● Many Americans still can’t understand why Sandy Hook wasn’t the tipping point in the gun debate. Who could argue for the sanctity of the Second Amendment above all else in the face of distraught parents of murdered six- and seven-year-olds?

As it turned out, it was frighteningly easy to dismiss emotional parents as being too compromised by their grief to weigh in on gun policy. Never mind that some of those same individuals were gun owners themselves. Because the shooter suffered from obvious social and emotional issues, the debate was quickly redirected into a discussion of failures in our mental-health system. This was not a gun problem but a psychological problem.

In the end, a coalition of anguished parents wasn’t strong enough to counter the NRA. Neither were the deaths of forty-nine victims in the June 2016 rampage at Pulse nightclub in Orlando or the shooting on the Las Vegas Strip on October 1, 2017, where fifty-eight people were killed and 422 were wounded by bullets, or the massacre of twenty-five people a month later at the First Baptist Church in Sutherland Springs, Texas.

● I take my phone to the bathroom because I’m afraid I’ll miss an AP alert that’s going to tell me there’s been another shooting. The one about the Pulse nightclub was posted just before dawn. After these multiple-casualty attacks, I compile photos to accompany eulogies on The Trace’s Twitter feed. We started doing this for the victims at Pulse because there were so many casualties and we didn’t want the people to get lost behind a number — we wanted to put faces to names. Now I do it after every mass shooting. As I crop the photos, arrange them into a collage, and type out the names, I’m consumed by the feeling that everything has to be perfect. I have so little power over anything; the only power I have is to make sure everyone’s names are spelled right.

● When a mass shooting happens, friends reach out by text or on Facebook. They’re looking to me for the horrible details. But they’re also looking for clues to the larger narrative that will emerge. For Charleston, it was the gunman posing with the Confederate flag and the FBI’s failure to act on its own information. For the First Baptist Church in Sutherland Springs, it was the use of the semiautomatic AR-15 rifle that had just been used in Las Vegas and the shooter’s domestic-violence conviction that the Air Force had never forwarded to the FBI. For the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting, it was the gunman’s anti-Semitic, anti-immigrant posts on a far-right social network. That’s what they’re looking for from me: the takeaway. What’s the issue that’s been exposed?

● I guess my background predisposed me to this line of journalism. Before I was born, my father had served twelve years in prison for gunning down a police informant. Years after his death from lung cancer in 2001, I learned that he’d killed many more people during his time as a drug dealer and mafia associate in Brooklyn and Miami in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s. In an attempt to comprehend how my doting father — who I knew as a genial carpet cleaner — could be a brazen assassin, and how my mother — a former high-school English teacher who’d toiled in violent East New York — could forgive his crimes, I began investigating his past. Shortly before I graduated from the J-school, I turned the story into a Modern Love column in the Times. In 2010, I explored it again in a memoir.

And what I found after all this searching was this: guns made it easy for my father to kill people.

● I have an Italian last name, but my mom was Jewish. My grandmother came here from Ukraine to escape the pogroms. Five days after the Pittsburgh shooting, a group of girls in school uniforms were handing out Shabbat candles outside my office. One of them came up to me and said, “Are you Jewish?” I hesitated. For the first time in my life, I was afraid to answer.

● I have a coping mechanism: I sleep all weekend. I try to be comatose as long as I can. But despite my fears and bouts of real pessimism, when people ask me how I feel about the chances for meaningful political reform, I tell them I’m more optimistic than I was a year ago. The conversations around guns are changing.

● On my way to work, I pass a charter school that boasts “world-class progressive education for the children of Harlem.” While violent crime has dropped significantly in New York City over the last two decades — I’ve heard gunshots maybe half a dozen times in the eighteen years I’ve lived in Harlem — when it does occur, these kids are among the most likely to be exposed to it. They may not encounter as many firearms as their peers in, say, a gun-friendly south Florida suburb, where some families spend Sundays at the range, but it’s a good bet that they see more gun crime.

Which is why when I was passing by the school last February, I stopped in my tracks. Hanging in the window was a floor-to-ceiling bright-yellow poster dotted with figures that resembled chalk outlines of dead bodies at crime scenes. Written on each of these figures was a name and an age: Meadow Pollack, 18. Helena Ramsay, 17. Alex Schachter, 14. They were the seventeen victims — fourteen students and three teachers — of Parkland. Around the outlines were messages scrawled in red ink: “Sending love and strength to the students in Parkland, FL.” “put the guns down!” “Keep your head up.”

Until Parkland, I’d never seen children of color in a low-income neighborhood that’s disproportionately affected by gun violence memorialize the mostly white, upper-middle-class victims of a mass shooting. That’s when I knew something was changing.

● David Hogg, a senior at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, filmed the lockdown that accompanied the massacre at his school on February 14, 2018. The videos, which show Hogg and fellow students hiding in a dark closet and calmly and rationally articulating their fear and fury, quickly went viral. At the time, Hogg wasn’t thinking politically. “I recorded those videos because I didn’t know if I was going to survive,” he told the New York Times.

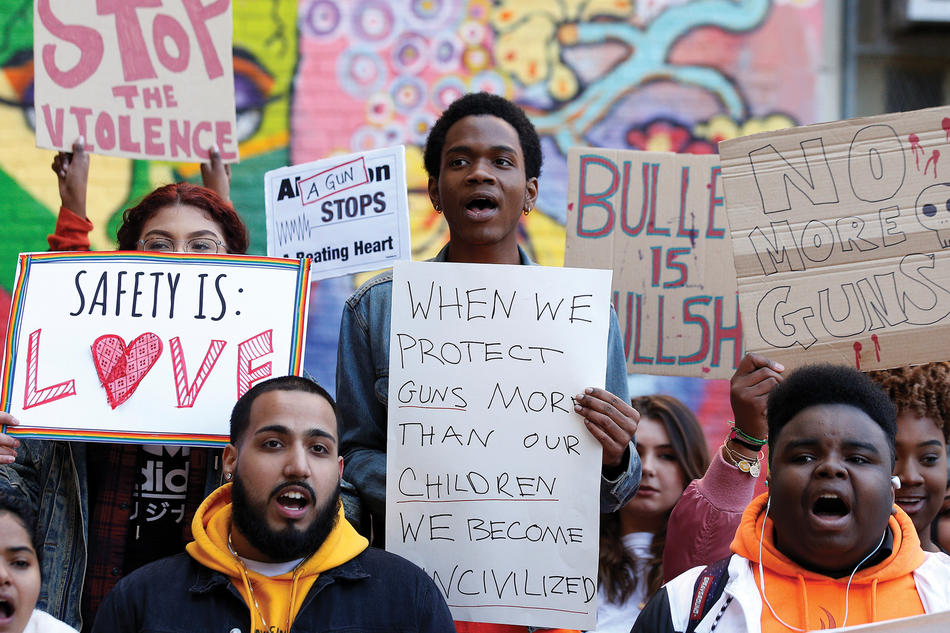

Too young to be ideologues, the teenage survivors didn’t traffic in rhetoric or campaign slogans. What they were expressing was pure, unvarnished emotion. Here were kids fed up with gun violence — and the failure of elected officials to do anything about it. Fueled by that outrage, the Parkland kids set out to reinvent a fifty-year-old gun-reform movement and thrust it into the mainstream.

● Before February 2018, the idea that teenage survivors of a school shooting would be able to corral hundreds of thousands of their peers into the street to advocate for gun reform — a political third rail if there ever was one — and manage to dominate a news agenda led by a head-spinning number of domestic and international scandals would have seemed outlandish. But the Parkland teens weren’t easy to dismiss. Unlike the family members who turn to gun-reform advocacy after losing a loved one to a mass shooting, the kids in Florida had lived through one. Like soldiers, they’d seen and smelled and dodged and fled, and reported back that, contrary to the NRA’s argument that “the only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun,” having a firearm would not have prevented a shooting that was over almost before it began.

● March for Our Lives, the March 24, 2018, protest for gun reform organized by the Parkland students, drew 1.2 million people across the US, making it one of the biggest youth protests since the Vietnam War. Veterans joined the call for tighter regulations on firearms. Some of the proposals articulated by the Parkland students (which were later embodied in a manifesto) became Florida law. In fact, a mere three weeks after the shooting, the same Republican-dominated legislature that has permitted an NRA lobbyist to have the final say on gun legislation for the last several decades passed a series of gun laws that incorporated proposals from a group of teenagers.

When has that ever happened? Never, that’s when.

● Since the massacre, state legislatures have passed at least fifty gun regulations. Twelve states have enacted so-called red-flag laws, which enable law enforcement, and sometimes family members, to petition a judge to remove guns from potentially dangerous people. The pro-gun governor of Vermont signed into law a slew of gun reforms. And, for the first time in decades, lawmakers are not afraid to campaign on the issue.

● From the perspective of someone who devotes all her time and energy to America’s gun-violence problem, the Parkland students have had a major impact. Though they were called “crisis actors” by trolls, their social-media savvy pushed them above the din and nudged the National Rifle Association closer to the fringes. Gun-rights advocates have defined the debate for decades, claiming the moral high ground in their defense of the constitutional right to bear arms. But in the wake of Parkland, the NRA has lost dozens of corporate partners, been cited multiple times for violating campaign-finance laws, and suffered a sharp decline in membership.

● During the summer of 2018, the Parkland survivors started a nationwide voter-registration drive in an effort to build a voting bloc formidable enough to rival NRA supporters. Youth voter registration went up 41 percent in Florida in the six months after the shooting, and a surge has also been recorded across the country. According to one survey, voters eighteen to twenty-nine made up 31 percent of the electorate in the recent midterm elections, compared to 21 percent in the last midterms, in 2014.

● The recent midterms saw the toppling of more than two dozen NRA-backed candidates across the US. “Overall, this country chose to move in the direction of gun safety,” Fred Guttenberg, the father of fourteen-year-old Parkland victim Jaime Guttenberg, tweeted on November 7. Indeed, as this magazine went to press, pro-gun-reform Democrats had gained seven governorships and flipped six state legislative chambers.

Two parents of murdered children won their races after making gun control the centerpiece of their campaigns. Lucy McBath, an African-American businesswoman whose son Jordan was shot six years ago by a white man angry over the loud music coming from his car, defeated her NRA-backed Republican challenger in the race for Georgia’s Sixth Congressional District. In Colorado, Tom Sullivan, whose son Alex was one of twelve people gunned down in an Aurora, Colorado, movie theater in 2012, won a state House of Representatives seat in an upset. “I think what I did is something any father would do for their child,” Sullivan, choking back tears, told a local reporter after his victory.

● If we are to decrease shooting deaths in America, we must shift some entrenched attitudes about gun ownership and safety. That will probably take decades. But change is already happening: the Parkland kids have forced many gun owners to reflect on the place of guns in American society. And today’s high-school students who are building their political identity around gun reform are tomorrow’s college students and parents and elected representatives. Their activism is giving the gun-reform movement its best chance in a generation to succeed, and perhaps one day, when mass shootings are an anomaly and not a regular occurrence, we’ll be able to look back and remember exactly when things began to change: on February 14, 2018, at a suburban high school in south Florida, with a massacre that proved to be one too many for our kids to tolerate.