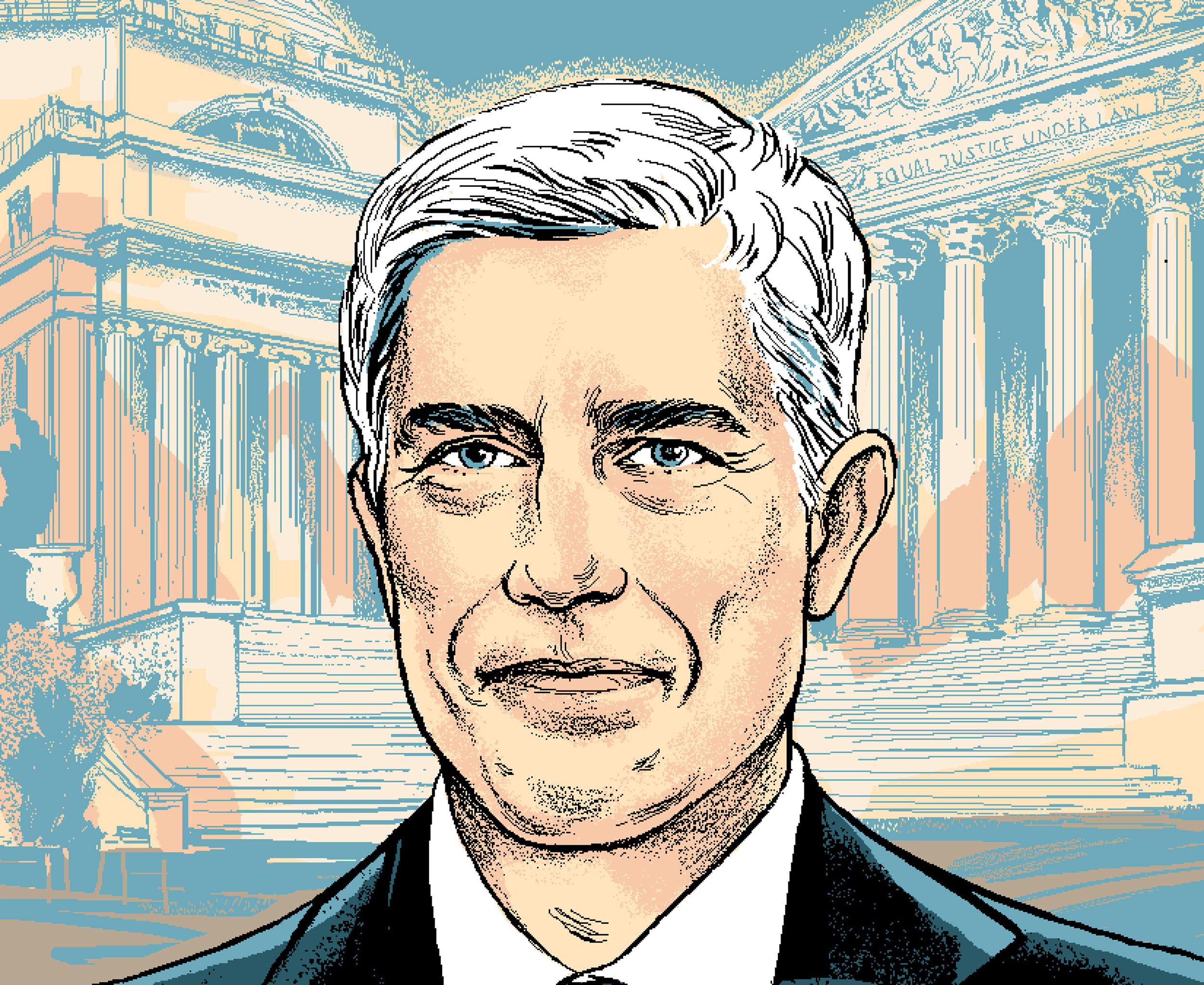

In January, when President Donald J. Trump nominated Neil McGill Gorsuch ’88CC to fill the Supreme Court seat left vacant by the death of Antonin Scalia, politicos immediately scrambled to find out more about this critical appointee and what he stood for. Senators picked through Gorsuch’s ten-year record as a judge for the US Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit, while the press delved into his formative years, especially the ones he spent as an undergraduate at Columbia.

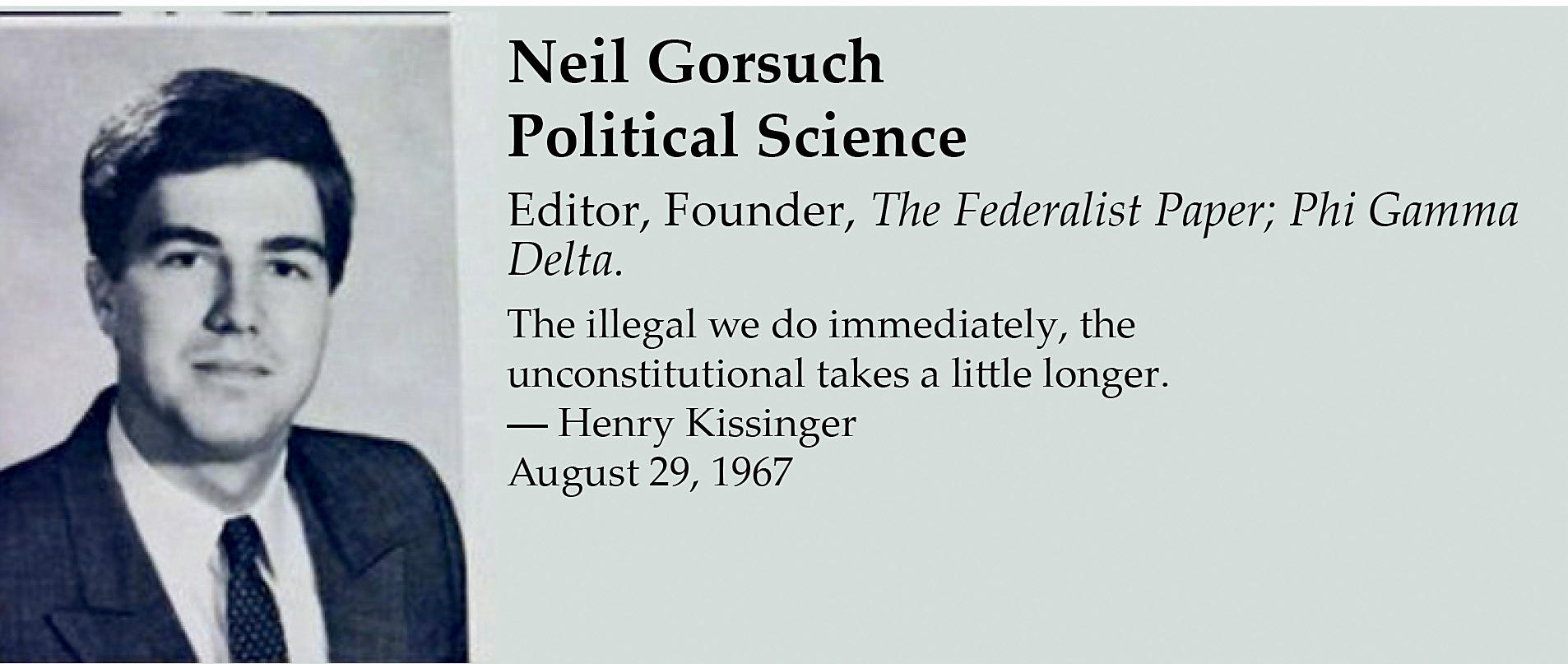

There was plenty to sift through. In the 1980s, the popularity of President Ronald Reagan triggered what the New York Times later called a “youthquake of conservative campus activism,” and Gorsuch was one of Columbia College’s most prolific conservatives. A contributor to Spectator and a cofounder of the alternative tabloid the Federalist Paper, Gorsuch published editorials and columns that expressed support for the Contras in Nicaragua, pushed back against the campus’s “tyrannical atmosphere” of reflexive liberalism, and criticized left-wing activists for their “muddled thinking” and “vigilante justice.” Much was made of his yearbook quote, a sardonic quip from Henry Kissinger: “The illegal we do immediately, the unconstitutional takes a little longer.”

Back then, these sentiments earned Gorsuch a reputation as a rabble-rouser. But thirty years later, many who knew him in college are eager to share a more nuanced view of the young man who came to Columbia determined to leave his mark. Some remember his intelligence and charm, others his dry humor. Even those who disagreed with him give him credit for stirring up vigorous debate on a predominantly liberal campus.

Indeed, during Gorsuch’s confirmation hearings in March, more than 150 of his Columbia and Barnard compatriots presented a petition to leading members of the Senate supporting his nomination. “The hallmark of Neil Gorsuch’s tenure at Columbia was his unflagging commitment to respectful and open dialogue on campus,” the petition stated. The signatories were mixed politically, ethnically, economically, geographically, religiously, and professionally. But their verdict was unanimous: “Despite an often contentious environment, Neil was a steadfast believer that we could disagree without being disagreeable.”

Gorsuch wasn’t just interested in establishing his own socially and politically conservative voice, says Federalist Paper cofounder P. T. Waters ’88CC, now managing director of Himmelsbach Holdings, a clean-fuel technology company. “What he really wanted was the John Lockean discussion of ideas. He wanted an open and fair debate.”

While Justice Gorsuch is not currently giving interviews, his credentials are a matter of record. He graduated Columbia Phi Beta Kappa and with a prestigious Truman Scholarship. In 1991 he earned Latin honors at Harvard Law School, where one of his classmates was Barack Obama ’83CC. He clerked for retired Supreme Court associate justice Byron R. White and sitting associate justice Anthony M. Kennedy. His impressive academic career culminated in a doctorate from Oxford in 2004. From 1995 to 2005 he worked in the Washington, DC, law firm of Kellogg, Huber, Hansen, Todd, Evans & Figel as a litigator (he became a partner in 1998), and he later served as principal deputy to Associate Attorney General Robert McCallum under President George W. Bush.

When Gorsuch was confirmed in April by a Senate vote of 54–45, he became the eighth Columbia graduate to reach the high court, joining John Jay 1764KC, Samuel Blatchford 1837CC, Benjamin Cardozo 1889CC, 1890GSAS, 1915HON, Charles Evans Hughes 1884LAW, 1907HON, Harlan Fiske Stone 1898LAW, William O. Douglas ’25LAW, ’79HON and Ruth Bader Ginsburg ’59LAW, ’94HON. As the court’s newest and youngest justice, Gorsuch swiftly asserted himself as the conservative voice that the Republican Senate had held out for when they stalled President Obama’s nominee, Merrick Garland, in 2016. And Gorsuch’s early opinions as a Supreme Court justice suggest that the conservatism he espoused at Columbia has been a consistent guiding philosophy.

After spending his early childhood in Denver and his high-school years in Maryland, where he attended North Bethesda’s Georgetown Prep (Waters was a classmate there), Gorsuch seemed to arrive on 116th Street with his worldview in place. “He was a bit more fully formed than other people, intellectually,” says Fed cofounder Dean Pride ’88CC, now a writer and copyeditor for Mishpacha magazine in Israel.

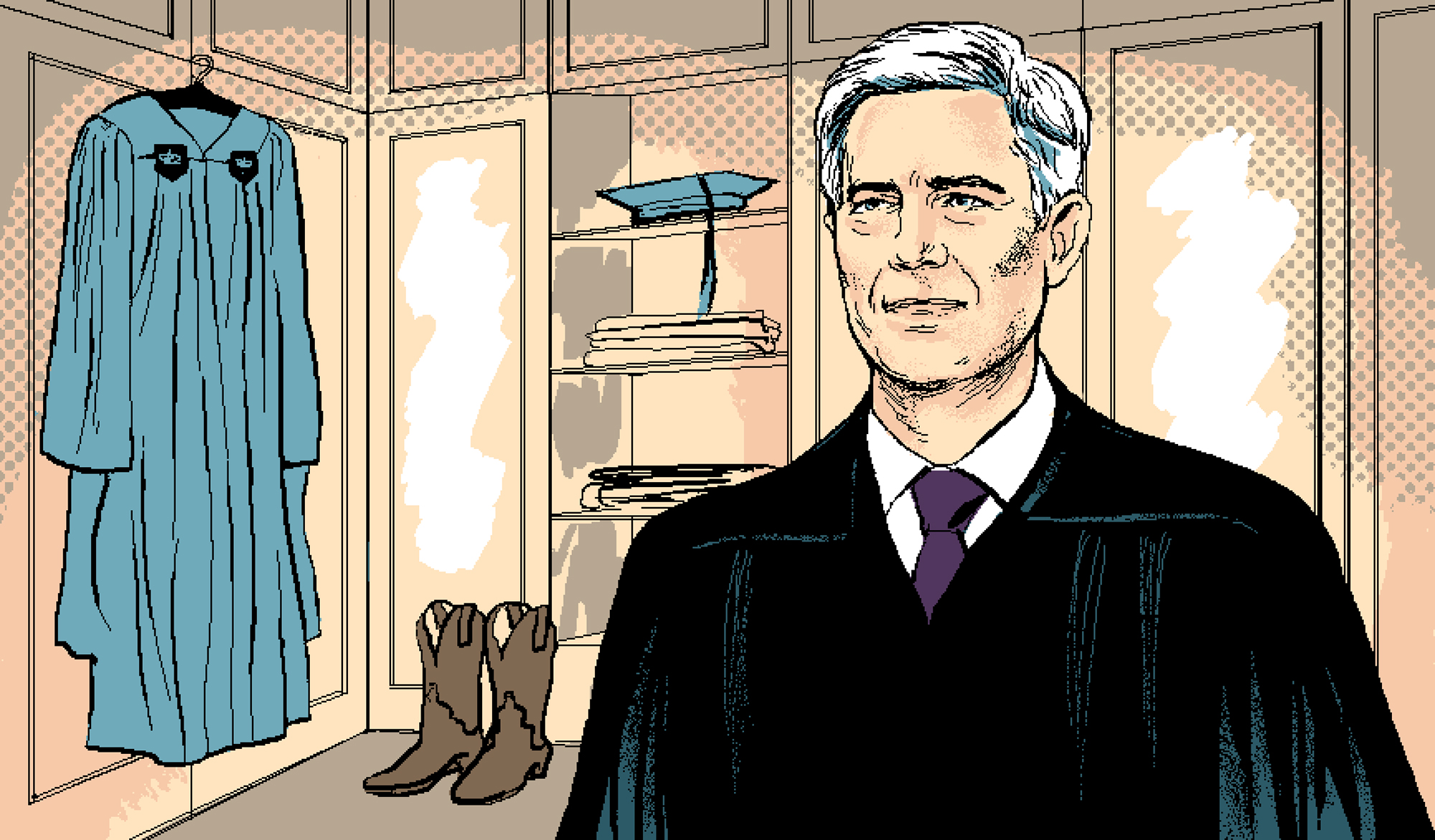

Gorsuch was also extremely driven. Though he entered with the Class of 1989, he piled on the courses and graduated in three years. “He did seem like a man in a hurry,” says Waters. “He was always rushing — physically, literally.” Sometimes he did so in cowboy boots.

“He was a smart cookie by the time he got to school,” recalls attorney Robert Laplaca ’89CC, one of his fraternity brothers at Phi Gamma Delta (“Fiji”). “I used to joke with him that he’d become president someday, just because of his demeanor, his likability, his intelligence, and his thinking on big issues.”

At the same time, Gorsuch was in many ways a typical college student. He studied, dated, and hung out. In retrospect, some of his acquaintances wonder why he pledged Fiji, which had a reputation for partying. But his Fiji brother and Fed colleague Dave Vatti ’89CC, today a federal prosecutor in Connecticut, finds nothing unusual about his membership. “Neil liked being one of the guys and having fun, and that was what Fiji was all about.”

If not a loner, Gorsuch was also not quite a joiner; he did not live in the Fiji house at 538 West 114th Street. Classmates claim that he refused to be photographed with a beer in his hand, in case he ran for public office one day. As it was, he was disqualified from his 1986 bid for the University Senate because of inappropriate campaign-flyer placement. Spectator reported that the elections commission “found several of Gorsuch’s posters in East Campus elevators, more than two posters on several floors in various dorms, and posters taped to the glass portions of doors in dorms — all violations of election postering rules.” The candidate said he was unaware of the two-poster rule and that his supporters were responsible. (Laplaca recently fessed up: “I was the dummy who violated the sign-posting rules,” he wrote in a letter to Columbia College Today this past spring.)

“He was an unfailingly polite, gracious person,” says Pride. “In an argument, he could get sharp. He has a way with words. But in his personal dealings with people, I don’t think anyone would have said that he wasn’t a good guy.”

Elizabeth Pleshette ’89CC, a future College admissions officer and a neighbor on the twelfth floor of Carman Hall, agrees. She would frequently tussle with Gorsuch in the floor lounge over abortion and reproductive rights.

“We got into tremendously heated discussions, to the point that people would walk away in disgust — ‘Oh, it’s Neil and Liz again.’ I would get very emotional, and it would be very upsetting.” But Pleshette remembers another, more homespun aspect of her verbal sparring partner: “He sounded like Jimmy Stewart. We teased him about it. He was the quintessential ‘gee willikers’ kind of guy.”

In addition to his beliefs, ambition, and poise, Gorsuch came to campus with noteworthy family ties: his mother was Anne Gorsuch Burford, the former head of the Environmental Protection Agency. Under President Reagan, she aroused liberal wrath for relaxing pollution rules, and for cutting budgets and employee rolls alike. When she declined to turn over subpoenaed documents related to the federal Superfund program, she became the first cabinet-level official to be cited for contempt of Congress. After twenty-two months, she resigned.

Her son’s friends and detractors are unanimous in saying that Gorsuch downplayed this background — not necessarily because he feared notoriety, but because he wanted to be known in his own right.

As a freshman, Gorsuch wrote for a short-lived journal of ideas called the Morningside Review (not to be confused with the current online journal of that name published by the undergraduate writing program). In one piece, titled “A Tory Defense,” he wrote, “Here on Morningside, conservatism is an undeniably fashionable whipping-boy for the world’s ills.” But along with his Morningside contributors Pride and Andrew Levy ’88CC, Gorsuch found the publication lacking. “It had no campus visibility,” says Levy, a senior producer at the HLN network and a former Fox News commentator. “It was sort of like shouting into the wind.” Pride remembers Morningside being wonky, infrequent, and too focused on national and global affairs: “It wasn’t quite a student publication,” he says. “We wanted something a bit more lively.”

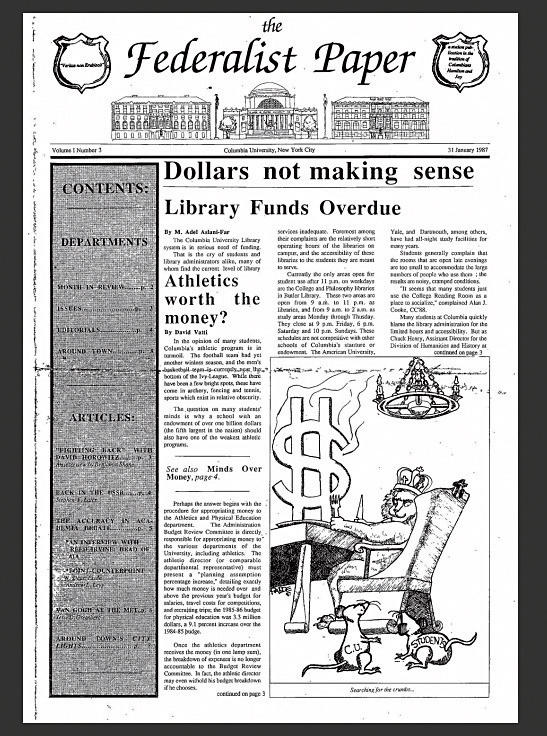

So in October 1986, Gorsuch, Pride, Waters, and Levy started the Federalist Paper as a feisty and reliable response to campus liberals.

“We were wondering if someone could open a forum for debate — a real debate — that would keep some important issues in the Columbia College student’s mind,” Gorsuch told Columbia College Today at the time. “Maybe even provide him with a few different perspectives he hadn’t heard, but which do exist on campus. And we thought we could do it.”

“Neil was the straw that stirred the drink,” says Waters. “He founded that paper, and it was his paper. We had an editorial board, and he was not autocratic. But it would not have happened without Neil.”

Even the publication’s name was Gorsuch’s decision. Levy had waited to call it the Columbia Independent, but Gorsuch insisted otherwise. The moniker was, of course, an homage to the classic defenses of the Constitution written by John Jay, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison. Gorsuch’s Spec column was appropriately titled “Fed Up.”

The Federalist Paper (which still publishes as the Federalist, but with an emphasis on satire) was far from an ideological monolith. There were pro-and-con forums; one early column objected to then Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork’s “extremist tendencies.” Much of the subject matter was strictly parochial. A piece in the October 26, 1987, issue questioned whether students were getting enough study time before final exams. Another scrutinized wide grading disparities among professors of the four basic Core courses.

The staff, too, was a mixed bag. Pride was a New Deal liberal, Levy a libertarian who embraced the Objectivism of Ayn Rand, and Gorsuch a devotee of Edmund Burke, with his faith in traditional, established institutions. Fed editorial meetings, Columbia College Today reported, often yielded “red-faced debate.”

“If we tried to reach editorial consensus on every piece we published, we’d never publish,” Gorsuch said in the article. “It’s a tough staff to keep together because there are very deep divisions, very strongly felt ones.” The future justice told D. Keith Mano ’63CC in National Review in 1987, “[The] reason why we can be so diverse is that there is so much room to the right. It’s not a matter of having to be a conservative to be identified with the right, it’s a matter of being a thinking man or woman.”

The Fed often aligned itself with mainstream Republican Party policies — anti-Soviet, anti-Sandinista. Much of its more outrageous commentary emanated from the fictitious and semi-satirical “Pierre du Pont Copeland,” a collaboratively constructed character described by Waters as “a very arrogant, wealthy” General Studies student — a sort of comic embodiment of the left’s worst nightmares. “I believe in the trickle-down theory: the servants’ bathrooms are directly below mine” was a typical Pierre pronouncement. “A person in jail for tax evasion (theft evasion) is as much a political prisoner as Nelson Mandela” was another.

At one point, Pierre joshed about how he and his cousins raised geese, tagged them with “the names of our favourite [sic] bleeding hearts,” and then hunted them on the Delmarva Peninsula. Among their kills were “Biden” and “Cuomo.” Pierre added, “We always make sure to have at least two or three corpulent ones, which we nickname ‘Teddy’ or ‘Tip.’”

But as Waters remembers it, Gorsuch objected to cheap shots and tried to keep them out of the Fed — not always successfully. “We’d gang up on him and he’d say, ‘OK, OK, OK.’ But he did not like it at all.” Indeed, says Levy, “On his deathbed, Neil would not say that publishing Pierre was one of the highlights of his life.”

For all their acerbity, Gorsuch and his Fed cohort eschewed the incendiary tone of the Dartmouth Review, the lodestar of the then-budding student conservative press movement and a hothouse for such right-wing firebrands as Dinesh D’Souza and Laura Ingraham. “Other than wanting to be as widely read as the Dartmouth Review on their campus,” Levy says, “I don’t remember us wanting to emulate them.”

Many of Gorsuch’s most keenly felt opinions found expression not in the Fed but in Spectator. Nor were they all politically charged. In February 1988 he pleaded for greater resources for the College, because it was “overcrowded, overburdened, and ever more subservient to the University’s graduate programs and Vice Presidents.” The following month, he urged that Student Council candidates address such pressing matters as the inadequacy of the college library in Butler, the need for a good book co-op, and the College’s “dismal support for its athletes.” With proper attention, Gorsuch argued, Columbia could become “a first-choice school.”

Gorsuch seemed to enjoy being provocative. In an April 1986 column he mocked a South Africa–type shanty that had gone up on Low Plaza as a “pre-fabricated, simple and fashionable” knockoff of Dartmouth’s more authentic “crickety and battered” counterpart. He called the divestment movement “unquestionably an honorable one.” But given that the Trustees had voted to divest the summer before, Gorsuch suggested, the structure had been erected “solely for media coverage.”

“He had very strong views that he expressed well,” says Andrea Miller ’89CC, now president of the National Institute for Reproductive Health in New York. As an editorial-page editor at Spectator, Miller says she felt an obligation to publish the full range of student opinions, but she recalls a “tenor of dismissiveness” in Gorsuch’s writing.

“If you read his stuff, you can see that he would very rarely engage the content of the argument someone was making,” says Tom Kamber ’89CC, who is executive director of Older Adults Technology Services, which connects senior citizens to the digital age. “Invariably he was questioning motives.”

Still, Kamber quickly volunteers that he liked Gorsuch personally. In 1985, both of them lost the National Speech and Debate Association’s Lincoln-Douglas Debate at the organization’s national championships. When Kamber sought refuge in drink, Gorsuch consoled him, literally patting him on the back.

Elizabeth King Humphrey ’88CC, a freelance writer and editor in North Carolina, and a signer of the pro-Gorsuch petition, points to the number of signatories as testament to Gorsuch’s personal appeal. “When you spoke with him you could tell he respected you,” she says. “If I didn’t feel that way, I wouldn’t have kept up with him all these years.”

In face-to-face discussion, Kamber, too, found Gorsuch delightful. “We would argue for hours, and it was a lot of fun. He was a fascinating guy to talk to. We had a friendly rivalry. It was a private debating club of two people.”

Their most memorable dustup came when Kamber, a University senator, suggested that Columbia’s fraternities might be compelled to admit women (the College went coed in 1983). The notion became a cause célèbre, spawned a movement on campus called Students for a Reformed Fraternity System, and culminated in a point-counterpoint in the March 7, 1988, issue of the Fed.

Defending Kamber’s position, Nancy Murphy ’89CC wrote, “Single-sex fraternities pose an immediate threat to all Columbia students . . . Women who are barred from fraternities by accident of birth face tangible harm.” She equated all-male Greek houses with “slavery and segregation, clear evils [that] were long supported by law simply because they were cultural institutions.”

Gorsuch and his Fiji brother Michael Behringer ’89CC (currently president of the Columbia College Alumni Association) countered the “righteous reformers.” Calling forced coeducation of fraternities “absurd,” they argued for freedom of choice: “What such heavy-handed moralism misses is the fact that Columbia is a pluralistic University, that its fraternity system is equally pluralistic, with options available for everyone. There is no one at Columbia who cannot join a fraternity or initiate a new one if they wish to do so.” Noting that “three all-women fraternities/sororities” had lately been formed, Gorsuch and Behringer asserted that Kamber’s forces were “incapable of mustering a stable argument against the system as a whole.”

All of this, of course, raises the question: why would Gorsuch attend a college where his views would not only be in the minority, but also draw strong opposition?

Elizabeth Pleshette offers this insight: “We would frequently say to him, ‘Why are you here? Everything upsets you. You think all of these liberal students are so frivolous.’ We were always challenging him. And he said he wanted to be in the belly of the beast to test himself. He said, ‘This is going to hone me. If I surrounded myself with like-minded students, I wouldn’t get stronger.’”

“Neil often told me that he elected to attend Columbia for two reasons: the Core Curriculum and the rich diversity of Columbia’s student body,” Behringer wrote in a Facebook post the day the Senate confirmed Gorsuch’s nomination.

Perhaps that combination gave Gorsuch the ability to probe his opponents’ beliefs, the better to counter them. Or perhaps it opened his mind, preparing him for when he might have to sit on a high court in dispassionate judgment.

Former Fed editor Eric Prager ’90CC, now a partner at a New York City law firm, finds truth in both these theories. Either way, Prager pegged his old friend three decades ago.

“It’s a trite expression,” Prager says, “but it captures what I feel: I thought he was destined for greatness.”