"About a thousand specialists drawn from all parts of the world worked at it, and they were not all there to help,” wrote Columbia history professor James Shotwell 1900GSAS in the summer of 1919, weeks after the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, an eighty-thousand-word pact that formally ended the Great War. Calling it “the most difficult of Treaties that has ever been made,” Shotwell, one of the agreement’s exhausted architects, agonized that “there is hardly a clause in the whole long document that has not been the object of controversy and debate.”

Shotwell belonged to a group of 150 American academics secretly convened by President Woodrow Wilson in September 1917 to analyze US and Allied policy around the world and create a plan for a postwar global order. This coterie was known as the Inquiry. Based at the American Geographical Society in New York, the Inquiry drew up what would become the Fourteen Points: Wilson’s principles for an enduring world peace.

The armistice was signed on November 11, 1918, and in December, Wilson and twenty-one Inquiry confreres, including Shotwell, boarded the SS George Washington and sailed for the peace conference in Paris. In February, Shotwell met with China’s delegate to the conference, Wellington Koo 1908CC, 1912GSAS, 1917HON, who had been his student. The two had lunch with some other College grads. “We had a very pleasant time,” Shotwell wrote, “and when I left the young people were singing Columbia songs around the piano.”

This was a rare bright spot in a mission undercut by secret treaties and competing aims. “Boundary making on the basis of statistics of population is difficult enough in itself,” observed Shotwell, “but is doubly difficult when measured up against the claims of culture and of history.” With Germany and Russia excluded from negotiations, France, Britain, and Italy pursued their own aims and imposed harsh terms on the vanquished Germans, thwarting Wilson’s goal of “peace without victory.” There was, lamented Shotwell, “hardly a single boundary which can be drawn that does not do violence to some important principle to which ... the Conference was pledged.”

On June 28, 1919, leaders of thirty-three nations gathered at Versailles to sign the treaty. As a nod to Wilson, the settlement included his fourteenth point: a call for a “general association of nations” affording “mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike.” From this demand, the League of Nations was born. China’s envoy was Koo.

The US Senate rejected American membership in the league, however, alarming liberal internationalists like Shotwell. “The more objections raised to the Treaty,” he wrote, “the greater the importance of the League of Nations as the one means of readjusting solutions and rectifying blunders. Otherwise, chaos, and chaos means the end of civilization.”

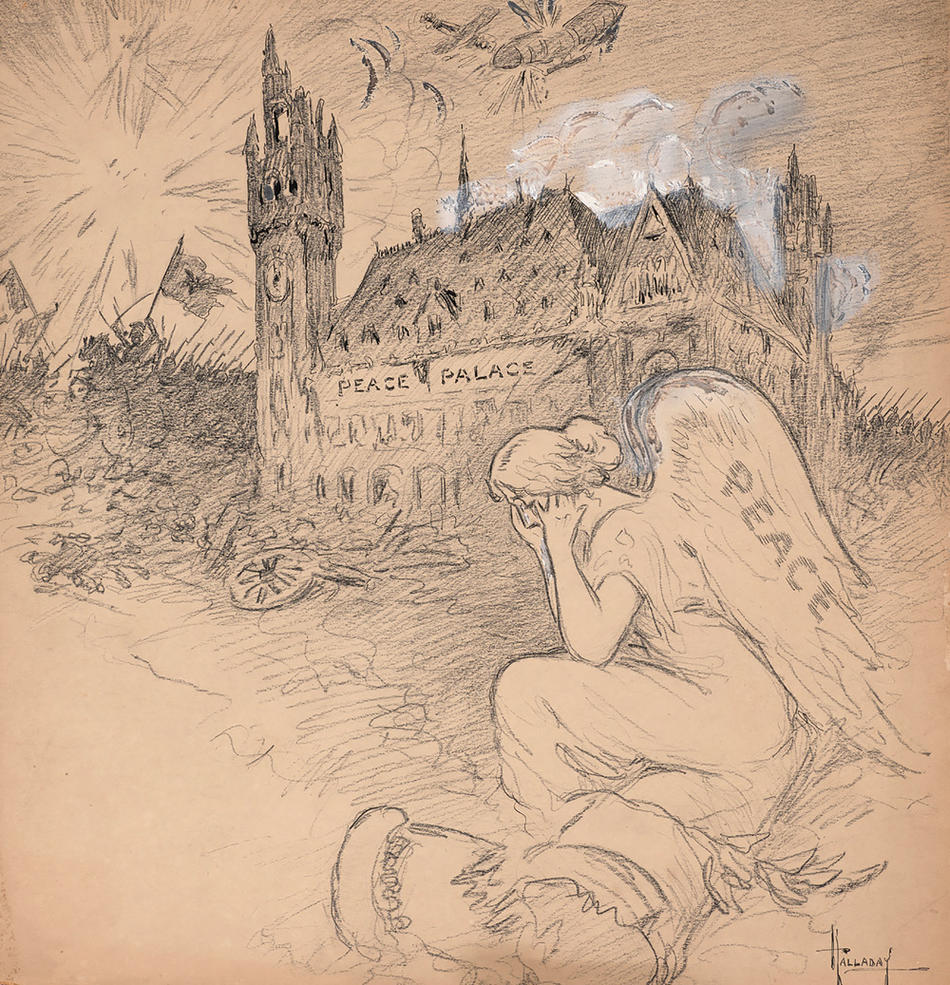

A new exhibit, “Remaking the World: Columbians and the 1919 Paris Peace Conference,” on view at the Rare Book and Manuscript Library from March 25 to July 19, gathers materials on the conference, featuring selections from the University-held papers of Shotwell and Koo. Both men remained committed to the League of Nations. Shotwell pushed for US membership into the 1930s, insisting on the league’s virtues even as it failed to enforce its own resolutions — and prevent another world war.

The League of Nations was disbanded in 1946 and replaced by the United Nations. Shotwell, who studied and taught at Columbia for nearly fifty years, helped organize the new world body, and Koo was one of the founding delegates.

This article appears in the Spring 2019 print edition with the title "Palace Intrigue."