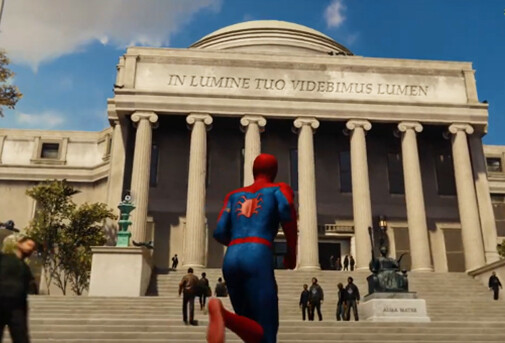

In 1988, Salman Rushdie, the Indian expatriate writer living in Great Britain, published The Satanic Verses, a novel. This exploration of the intermingling of cultures enraged some orthodox Muslims and garnered Rushdie a fatwa, or death sentence, from the Ayatollah Khomeini of Iran. Rushdie was forced into hiding. In December 1991, he quietly ventured outside Britain and emerged at a dinner held by the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the First Amendment and honor Associate Justice William J. Brennan Jr. Under heavy guard, Rushdie delivered an electrifying address, in which he declared that “free speech is life itself.” Rushdie never withdrew The Satanic Verses nor did he apologize for it, but in 1998, Khomeini’s successor revoked the fatwa. In the following excerpt, from a public interview with Columbia President Lee Bollinger conducted as part of the Midnight’s Children Humanities Festival, Rushdie discusses parallels between his artistic vision and his personal life, and the growth of his belief in free speech as an essential human need.

Bollinger: In your first appearance here, in 1991, you seemed to be in a state of abandonment, treated as somebody in a bubble, unable to have real human contact.

Rushdie: It was a very bad time. It was probably the worst time, actually, because as you say, until that moment I hadn’t really been able to fight back. Somewhat against my will, I’d really been kept out of the public eye, and for rather a long time hadn’t been able to find my corner. From that moment on I did begin to do that and immediately felt better. Thank goodness life isn’t like that anymore. At that time, everybody had an opinion about me—I mean, everybody. It was horrifying to have my character reinvented for me every day, 20 different ways, to have my motives described for me in ways which I didn’t recognize, to have my integrity questioned almost by the minute, to have my writing torn to pieces in front of my eyes.

Bollinger: How much of this has become of critical importance to your view of the world?

Rushdie: It folds into the category of Be Careful What You Wish For . . . because clearly, the subject of dislocation, migration, fracturing is what I was writing about, long before any of this happened. In Midnight’s Children, when the doctor at the beginning falls in love with a woman he sees only in bits, through a hole in a bed sheet, there is a fracturing of the woman, and then her assembly, in his mind, over a period of time, bit by bit. He glues her together in his imagination and then falls in love. That was also a figure of how the whole book was constructed—the world seen in fragments, but in some way united by the imagination of the writer, and of the reader. John Fowles wrote that without “whole sight” all the rest is sort of meaningless, but the world has become too fragmented and disputed a territory for anybody to claim to see everything. Against that Renaissance Man ideal, I wanted to invent a kind of broken mirror, a fractured reality.

And then it happened to my life. You know, we all live inside a picture of the world, which is how we think things are. If somebody smashes that, it’s a very scary thing, and you have to begin to put your picture of the world back together. That’s what I had to do in those years.

Bollinger: You’ve always spoken to freedom of speech. Why do you think this is one value we should insist upon?

Rushdie: I was obliged to learn about free speech, as an issue, by the process of somebody trying to take mine away. It’s when somebody starts turning off the air supply that you notice that it’s pretty important to be able to breathe. I became extremely conscious of what I had previously taken for granted. Going into writing The Satanic Verses, my position was that this was my life material, which belonged to me, and that I had a perfect right to explore it any way I chose. That there were people who disagreed with that made me, first of all, aware of how automatic my original position had been. I don’t particularly think of free speech as a Western value. It’s something—everywhere I’ve been in the world—people enjoy indulging in. And they don’t like it when they’re prevented from doing so.

Bollinger: So you think freedom of speech is a universal desire?

Rushdie: One way of approaching that question is to look at our actual nature as human beings, and what it is that is required for us to be the beings that we are. We are, as far as we know, the only self-conscious creatures in the world, and we are also, as far as I know, unique in that we are storytelling animals. We define ourselves by stories. Inside a family, there are family stories, and knowing the stories of the family is an important part of belonging. When a child is born or somebody marries into the family, gradually they are told the stories of the family, and when they know those, they are members. And in the end, when we die and generations move on, what remains is a story. If somebody tries to control that by deciding what we may speak about and what is permissible, we simply cannot be ourselves.

Bollinger: But some stories people tell are very offensive to others.

Rushdie: Yep, yep. That’s okay. There was a movie made about me, in which I was the bad guy. I was dressed in a very villainous series of safari suits. I had a whiskey bottle in this hand, and a whip in this hand, and a sword . . . and I torture a guerrilla brought to me by the Israeli Secret Service, and then I say, “Take him away and read to him from The Satanic Verses all night.” When they tried to bring the movie to England, the British board of film classification knew that I could sue them if they gave it a certificate [because it was libelous]. And so I had to write a formal, legal letter forgoing my legal right to sue and asking them to grant the certificate. The producers then booked a 2,000-seat cinema in the town of Bradford, in Yorkshire, which has the largest Muslim population in Britain. And nobody went, because nobody wanted to see a bad movie. It demonstrated the free-speech position, which is that people are able to make up their own minds. But had that film been banned, it would have become a hot video. Its power would have been multiplied.

Bollinger: At your talk at Columbia in 1991, you gave a self-description, in which you talked about holding on to your soul. You said, “No matter how great the storm, if that plunges me into contradiction and paradox, so be it. I’ve lived in that messy ocean all my life. I fished in it for my art. This turbulent sea was the sea outside my bedroom window in Bombay. It is the sea by which I was born and which I carry with me wherever I go.” Do you still agree with this as a description of yourself?

Rushdie: Yes. I mean, this really is the last thing to say: I think that democracy, freedom, art, literature—these are not tea parties, you know? These are turbulent, brawling, arguing, abrasive things. I’ve always seen the work of the imagination and the world of the intellect as being turbulent places. And, you know, out of turbulence come sparks, which are sometimes creative and sometimes not. But without that turbulence, in a calm sea, nothing happens.