One after the next, the honored professors arrived at the landmarked building on West 57th Street. Inside, they entered a high-ceilinged room, which was preserved in a kind of mid-century bohemian-intellectual glory: Persian carpets, red walls with gold filigree, bookcases and paintings, busts and lamps, tall bay windows hand-painted with Russian folk dancers. In the midst, under the chandelier, stood Adam Van Doren ’84CC, ’90GSAPP. He was talking about his grandfather, Mark Van Doren ’21GSAS, ’60HON, the poet, critic, memoirist, editor, Great Books promulgator, Pulitzer Prize winner, and the embodiment of the Platonic ideal of a Columbia professor, which he was for thirty-nine years.

“I never saw my grandfather teach, but I heard enough to know that for him, connecting with students was a matter of choice,” said Adam, a painter and filmmaker who teaches at Yale. “Some professors could give two beanstalks about connecting; they just regurgitate information and write their books.”

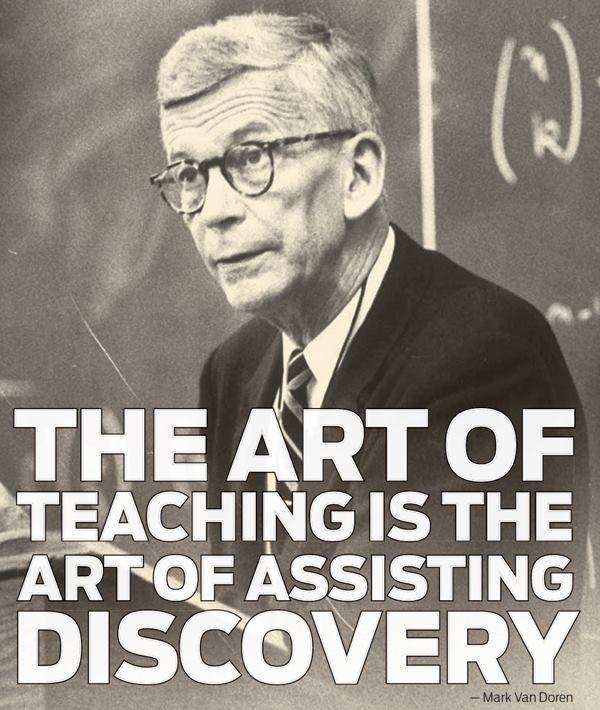

For Mark Van Doren, the art of teaching was “the art of assisting discovery,” as he wrote in his 1943 book Liberal Education. He would engage his Columbia College students as equals, with real inquisitiveness, wanting to learn along with them. Adam referred to The Seven Storey Mountain, the memoir by the Trappist monk Thomas Merton ’38CC, ’39GSAS, who devoted a long passage to his professor, writing of “Mark’s sober and sincere intellect, and his manner of dealing with his subject with perfect honesty and objectivity and without evasions.”

Near the wine-and-cheese table, past recipients of the Mark Van Doren Award for Teaching — which was established in 1962 and is conferred by students — chatted with members of the current awards committee, who would soon announce the 2017 winner, history professor Caterina Luigia Pizzigoni.

It was a hall-of-fame lineup of profs: Kenneth Jackson, Carol Gluck ’77GSAS, Michael Rosenthal ’67GSAS, Elizabeth Blackmar — thirteen in all. One waggish, sprightly eighty-five-year-old eminence — that would be Ted Tayler, famed professor of Shakespeare and Milton — was lamenting, with a twinkle, the widespread use these days, written and oral, of a certain four-letter word, which he enunciated delicately. He half blamed Allen Ginsberg ’48CC.

Tayler, a perennial student favorite, came to Columbia in 1960, a year after Van Doren’s retirement. Like Van Doren, he taught in Hamilton Hall for thirty-nine years. He hadn’t personally known the professor, who died in 1972, and was surprised as anyone to learn that Van Doren had sprung from the dusty loam of rural Illinois, and not, as some guests speculated, from New York Dutch nobility.

After all, in the 1930s, the Van Dorens were the New York literary establishment. Mark’s brother, Carl Van Doren 1911GSAS, was a literary critic and Pulitzer Prize–winning biographer; Carl’s wife, Irita Bradford Van Doren, was the books editor of the New York Herald Tribune; Mark’s wife, Dorothy Graffe Van Doren ’18BC, was a novelist and, like several other Van Dorens, an editor at the Nation. This explains Dorothy Parker’s line about her attempts to cure her insomnia: “I have even tried counting Van Dorens.”

Adam told of how Mark’s students, after class, still under the spell of his teaching, would follow him across campus, into the subway, and up to his front door in the Village. “My grandfather called it ‘the third thing,’” said Adam, describing the essence of Mark’s pedagogical method. “There’s you, there’s the teacher, and there’s what happens in between.” Adam understood why his grandfather was revered, and how he stayed friends with his students: Merton, Ginsberg, John Berryman ’36CC, Alfred Kazin ’38GSAS, Lionel Trilling ’25CC, ’38GSAS, Jack Kerouac ’44CC, and others. “There’s no generation gap when you’re connected with ideas,” Adam said.

As a student at Columbia himself, Adam was a regular at the Van Doren Award festivities. But it wasn’t until five years ago, when he revisited the ceremony and met former Columbia College dean Austin Quigley, that he learned about the selection process. Adam had assumed that the awards committee got together to vote “on one sleepless forty-eight-hour weekend.” But Quigley (who received the award in 2015) informed him that the students attend classes of prospective honorees and meet once a week over seven months to hash things out. Impressed and inspired, Adam decided to organize a gathering of the winners.

And here it was, a multi-generational get-together of practitioners and pupils, from the venerable Tayler to Adam’s daughter, Abbott Van Doren, a Columbia sophomore.

Adam praised the professors and saved his last word for those who brought out the best in the best teachers.

“To the students who make this all possible,” he said, glass in hand. “I salute you.”