Normally, Rolando Acosta ’79CC, ’82LAW cherishes shadows. Like the double play, shadows are a pitcher’s best friend, adding an extra layer of deception to a curveball as it flitters toward the batter through the dark lines cast by a tree or grandstand. But during a frigid afternoon last February, Acosta, four decades removed from his days as ace of the Lions’ pitching staff, became troubled when he looked out on Robertson Field and noticed a cluster of shadowy figures in the distance.

Acosta had been running on the track next to the diamond, trying to sneak in some exercise. Free time had become scarce since he’d been elected a New York Supreme Court justice in 2002. What puzzled him now was why, in such un-baseball-like weather, people were on the field — his field, the one he’d played on as a Lion and over which he felt a kind of guardianship.

That feeling is understandable, given what he achieved there. In the history of Columbia baseball, nobody has pitched more innings (336.2) or won more games (22) than Acosta. This slice of real estate at the northern tip of Manhattan is as much a home to him as the Dominican Republic, where he was born and raised. He often jokes that the only two things that matter in the DR are religion and baseball, and that sometimes it’s hard to tell the difference between the two.

Acosta’s childhood revolved around baseball. When he wasn’t playing it, he’d gather in the center of town with other poor kids to watch the San Francisco Giants on television. In the 1960s, the Giants were island favorites: their star pitcher was Juan Marichal, known as the “Dominican Dandy.” But Acosta’s parents wanted more for their kids. So, at the age of fourteen, Acosta moved with his parents and four siblings to the Bronx, where he had to learn a new language, a new measuring system, and a new culture.

Baseball, though — that was the same. Here, the mound was still 18.4 meters (or 60 feet, 6 inches) from home plate. Here, a catcher flashing an index finger still meant “bring the heat.” Upon arriving in the Bronx, it didn’t take long for Acosta to find the nearest pitcher’s mound — that little island where he felt most at home.

Home for Randell Kanemaru is Santa Ana, California. But on that February day, as wet snowflakes pelted his cleats and cap, home surely felt even farther away.

The sophomore second baseman took the 1 train up to Hal Robertson Field at Phillip Satow Stadium, where he joined a small group huddled on the infield. The snow was picking up, but when it landed on the field’s synthetic turf, it instantly melted.

“It doesn’t matter if it snows or rains,” Kanemaru says. “If it’s above 32 degrees, we’re definitely going to squeeze some work in.”

For college-baseball powerhouses like the University of Central Florida and the University of Houston, year-round mild weather is a major advantage. But what the Lions lack in climate they make up for in commitment (and synthetic turf). That’s why they’re out there on days when fly balls twist wildly in winter gales, and when cold metal bats punish your hands with a bone-rattling sting if you miss the sweet spot.

The hard work has paid off. From 2013 to 2015, the Lions won three consecutive Ivy League championships. The program is now capable of attracting even the most elite players, like Kanemaru, who, as a freshman, started 41 games and batted .296 on his way to being named the 2015 Ivy League Rookie of the Year. It was one of the best years by a Lion freshman since 1976, when a young right-hander notched 52 strikeouts in 73 innings and posted a 3.33 ERA. Those numbers belonged to the lone figure now poised by the running track, watching Kanemaru and his teammates.

“Hey, isn’t that the judge?”

The players waved, shouted hello, urged Acosta to come down and throw some batting practice. Acosta smiled and declined. The last time he accepted their invitation, his body couldn’t keep pace with his ageless competitive streak. He threw hard and he threw well, but he was so sore the next day that he couldn’t raise his arm to wash his hair.

So instead, Acosta planted himself on the third-base line and watched. He had an endless list of things to do: appeals to hear; decisions to write; Columbia trustee business to attend to; a workout to finish. But as the late-day sun began to push through the clouds, and the sound of balls popping in leather mitts echoed across the field, he knew he wasn’t going anywhere.

When Acosta first stood on the mound for Columbia in 1976, he was standing atop a tradition already more than a hundred years old. Columbia’s first recorded baseball game took place on May 27, 1867, when a group of young Columbia men, the Civil War and its raw lessons of mortality still fresh in their minds, happily traded bayonets for bats. They defeated a squad from NYU by the no-that’s-not-a-typo score of 43–21. The following fall, the team traveled to New Haven to face Yale. This was the last Columbia baseball game for almost two decades, and while the reason for the sport’s sudden disappearance remains unknown, one imagines that the 46–12 drubbing at the hands of the Elis didn’t exactly spread baseball fever across campus.

Baseball returned to Columbia in 1884, but the sport truly caught on in 1921 with the arrival of a student-athlete known around campus as “Biscuit Pants.” This moniker, a reference to the baggy trousers he wore over his thick lower body, was probably not one he relished. No matter: when the slugger, the quiet son of German immigrants, began launching majestic blasts that soared over the wall of old South Field, over 116th Street, and landed on the steps of Low Library, a new nickname took hold. “Biscuit Pants” would no longer suffice; he became known simply as “Columbia Lou,” a name that stuck on campus even after Lou Gehrig ’23CC left for Yankee Stadium to become one of the greatest hitters the game has ever known.

In 1930 the Lions joined the Eastern Intercollegiate Baseball League (EIBL), which included Army and Navy teams in addition to the traditional Ivy League. They had some early success, but as the decades wore on, the Lions’ luck faded, until they found themselves entering the 1976 season with a thirty-two-year championship drought (excluding a three-way share of the EIBL title in 1967). Harvard had a death grip on the league, gunning for a fifth straight title. Of course, they had yet to meet Columbia’s freshman pitcher, a kid from the Bronx who brought with him an electric fastball and something more than confidence.

“I didn’t exactly guarantee victory over Harvard in my interview with the Crimson,” Acosta recalls now with a wry grin. “But I came pretty close.”

Closer, at any rate, than Harvard bats came to Acosta’s pitches. Despite a hostile Harvard crowd jeering the freshman, Acosta took the mound with a cunning game plan and a sense of justice befitting a future judge.

“The best hitters are always crowding the plate,” he explains, “not letting you pitch to the inside corner. But I went out there with an attitude of, ‘Hey, that plate is just as much mine as it is yours.’”

Acosta owned the inside corner that day, shutting down Harvard in one of the great performances of a career that featured four straight All-Ivy honors and EIBL Pitcher of the Year honors in 1977 and 1979.

Today, you’ll find Acosta at most Lions home games, in dark sunglasses and a polo shirt, riding the umpire (“Come on, Blue! It’s right down the middle, Blue! You’ve got to call it both ways!”), and happy to recount those magical seasons. You won’t hear even a whisper of his honors. Instead, the Columbia Hall of Famer will proudly reel off the names of his teammates. He’ll gush about Mike Wilhite ’78CC, ’07GSAPP, the center fielder who batted .448 in 1977, and then, in 1978, hit eight home runs, breaking the Lions record set by Columbia Lou. He’ll recommend the baseball books written by pitcher Bob Klapisch ’79CC. He’ll tell you Paul Bunyan-esque tales of Bob Kimutis ’76CC, the 245-pounder so intimidating that opposing pitchers walked him 25 times in 29 games.

On April 23 of this year, in the middle of a Lions double-header against Princeton, the 1976 team gathered on Robertson Field to celebrate the fortieth anniversary of their championship season. When these guys get together, it’s like stepping into a time machine. Yes, Acosta is now officially titled the Honorable Rolando T. Acosta. But Bob Kimutis still calls him “Freshman.”

Among the ’76ers on hand that sunny Saturday was the coach, Dick Sakala ’62CC, who led the Lions from 1973 to 1977. Ask Sakala about Acosta, and he has two words: Juan Marichal. “That high leg kick, that beautiful motion. Rolando was our difference maker,” Sakala says. “We played three games a week, one on Friday and a double-header on Saturday, and we always started Rolando on Friday so that we could go into the weekend feeling relaxed.”

Right fielder Charlie Manzione ’76SEAS was there with his Worth aluminum bat, with which he hit .303 in 1976. He points to his head when he talks about Acosta. “Rolando was an extremely smart pitcher. He had this ability to read the hitter and set him up so that certain pitches were almost impossible to hit. And he’d locate his pitches: up and down, side to side. He never threw down the middle of the plate.” As for the team, Manzione says, “Everyone got along. No cliques, no personality questions. We had a great mix of upperclassmen and newer players, and we fed off of each other.”

Forty years later, the Lions, under coach Brett Boretti, are making their own history. Since Boretti took over in 2005, the Lions have won four Ivy League titles.“The coaches do a great job at building team culture,” says Kanemaru. “They’re different because they don’t necessarily recruit the guys who are the best players but the guys who are the best fit. We want the players who will become a part of our family, not selfish players who care about stats.”

A tight-knit clubhouse has become one of the program’s main selling points to recruits, and it’s yielded tremendous return. Kanemaru is a prime example. “Aside from Columbia, a few schools in California were recruiting me,” he says. “So I called around and asked about the environment on campus and in the locker room. I talked to Coach Boretti, and he really emphasized what the team is all about.”

Kanemaru hopes to soon join teammates George Thanopoulos ’16CC (drafted as a pitcher by the New York Mets), Jordan Serena ’15CC (drafted as an infielder by the Los Angeles Angels), and Gus Craig ’15SEAS (drafted as an outfielder by the Seattle Mariners) as a Major League Baseball draft pick. His 2016 numbers shouldn’t hurt his case: a .340 batting average (second on the team to infielder Will Savage’s .367), and a team-leading .573 slugging percentage.

Still, he considers himself as much a psychology major as a ballplayer. After all, like Acosta, Kanemaru chose Columbia primarily for the education.

“I know baseball won’t be there forever,” he says.

It’s a mature perspective. But someday, perhaps, Kanemaru will be like Acosta, sitting in the stands with his old teammates, telling stories of the past while watching the future, and he’ll know that this perspective, while wise, is not necessarily true.

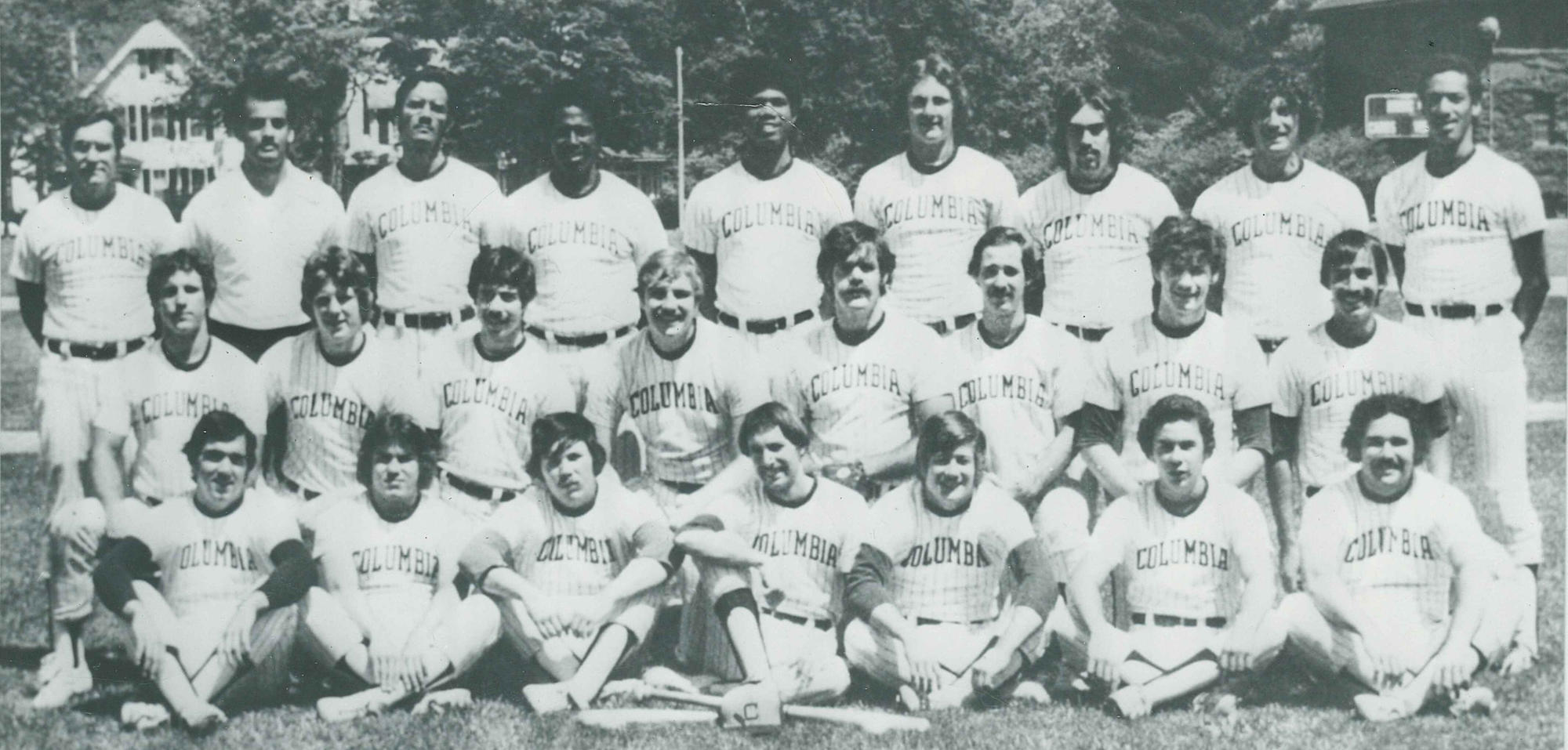

Diamonds are Forever: the 1976 Ivy League champs, then and now.