The city of Rahway, population thirty thousand, sits on the New Jersey Transit Northeast Corridor, thirty-eight minutes southwest of Penn Station. A former manufacturing hub, it retains, despite the new condo developments, the gritty brick-and-mortar charm of an American factory town. There are shingled houses and gabled roofs, a curving Main Street, and, by the river, a spindly-legged, pale-blue water tower with rahway stamped on its saucer-shaped tank.

On Irving Street, a couple of blocks from the YMCA and the movie house, sits Mr. Apple Pie, a scrappy little diner with a for sale sign in the window. The interior is small and narrow, with booths on the right and a lunch counter on the left. Handwritten cardboard signs tacked above the counter announce the specials, and on the walls hang three small Portuguese flags and a large American one.

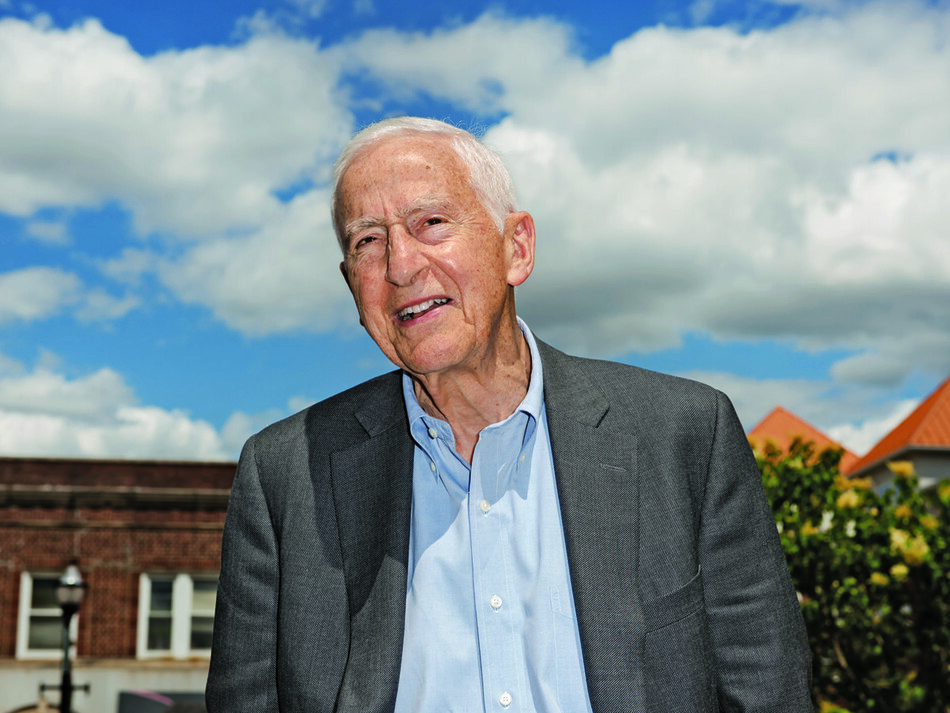

At 2 p.m. on a recent Friday, a slim man with white hair sporting a gray blazer over a blue shirt opens the diner door, setting bells tinkling. As P. Roy Vagelos ’54PS, ’90HON enters the establishment, his dark eyes fill with wonder. The counter used to be on the opposite side of the room. And the booths have been moved. Pulled by his curiosity, Vagelos takes long strides to the back of the restaurant and peers into the kitchen. The grill is in a different spot too. Vagelos resists an urge to go in and inspect further.

Returning to the dining room, Vagelos, eighty-eight, settles himself at a table, orders a slice of pie, and contemplates his improbable journey. Born in October 1929, three weeks before the stock-market crash, Pindaros Roy Vagelos, the son of Greek immigrants, spent much of his childhood in this place. It was here that Vagelos — shaped by the Great Depression and driven by a restless, competitive will — first set foot on his path to becoming a physician, a front-line biochemist, and a celebrated business leader. Over a seven-decade career, he has marshaled resources to fight disease, supported scholarships for students from immigrant backgrounds, and — through a revolutionary debt-free tuition program that began this year — changed medical education at Columbia forever.

When Herodotus and Marianthi Vagelos bought the restaurant in 1943, it was known as Estelle’s Luncheonette. The couple’s three kids — Roy, Helen, and Joan — helped run Estelle’s, and the family ate dinner there six nights a week. Roy, a violin-playing, sports-loving math whiz at Rahway High, worked behind the counter every day after school. He was a soda jerk, a dishwasher, a potato peeler.

He was also a listener. The suppertime crowd was mostly chemists and engineers from nearby Merck & Company, Rahway’s biggest employer. It was a time of great excitement in biochemistry. Multivitamins and antibiotics were being manufactured for the first time, and Roy in his apron soaked up the scientific shoptalk amid the clatter of forks and plates. He was impressed by these chemists and wanted to be like them — wanted to make medicines that would improve people’s lives.

“The customers inspired me,” Vagelos says. “And they encouraged me to pursue chemistry. Subjects involving memorization, like history or poetry, were difficult for me, because I had a terrible memory. But I could do math, and I could figure things out.”

Of course, as a working-class kid who had raised rabbits for meat during the war, he would need money for college. So Vagelos applied for scholarships, which, when he got them, allowed him to study chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania and, four years later, medicine at Columbia. “Going to Columbia changed everything,” he says, and his eyes brim as he recalls the Christmas party in Plainfield, New Jersey, during his second year of medical school, where he met Diana Touliatou ’55BC, a Barnard first-year from Washington Heights majoring in economics. Like Vagelos, Touliatou was the child of Greek immigrants and a scholarship recipient. They were married in the summer of 1955.

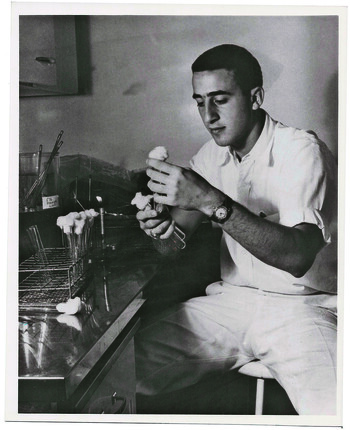

Vagelos did his residency at Massachusetts General Hospital, where he treated polio patients shortly before the first vaccine was licensed. He and Diana then moved to Washington, DC, so he could fulfill his two-year military requirement at the National Heart Institute. At NHI he worked in the lab of Earl Stadtman, one of the world’s leading biochemists, studying fatty-acid metabolism. A laboratory novice, Vagelos quickly found himself in an “anxious race” with world-class biochemists to understand how cells synthesize fatty acids. He delighted in the adrenaline-fueled eighteen-hour days, and, under Stadtman, his passion shifted from clinical medicine to research. “Earl was incredibly generous,” Vagelos says. “He would teach you for a while, and at the end of that time he would give you credit for everything you did. That’s very unusual. Most people will continue to put their name on your papers. Not Earl.”

Vagelos stayed at NHI until 1966, when he became chair of biochemistry at Washington University in St. Louis. The Vageloses built a nice life in the Midwest, with four kids and good friends. Then, in 1975, Roy got a call from back home: Merck wanted him to lead its research division. Vagelos, whose parents still lived in Rahway, could hardly pass it up.

At Merck, Vagelos changed the company’s method of drug discovery, encouraging his scientists to target disease causing enzymes and build compounds to block them. This led to the development of Mevacor — the first statin, or lipid reducer, to reach the US market. Vagelos oversaw the production of best-selling medications for heart disease, hypertension, and high cholesterol, and in 1985 he was named CEO. As a scientist, Vagelos brought an unorthodox style to the job. He was willing to learn from his subordinates, and he possessed thorough scientific knowledge of the products. But it was his response to the disease known as river blindness that brought Merck worldwide acclaim.

In 1987, the Merck drug Mectizan, an antiparasitic for pets and livestock, was shown in French trials to reverse and prevent river blindness, which afflicted tens of millions of people, mostly in West Africa. The disease is caused by river-bred blackflies, whose bites deposit larvae that spread through the body, causing severe itching, skin deformities, and, when the larvae reach the eyes, blindness.

Mectizan could defeat this blight with minimal or no side effects. But those at risk were too poor to afford the single tablet per year they needed. So Vagelos, who had tried without success to enlist the Reagan administration to help in the effort, came out with a statement: Merck would provide Mectizan free of charge to anyone who needed it, for as long as it was required.

It was a bombshell. Overnight, Merck became the poster child of corporate social responsibility. Profits rose, affirming Vagelos’s philosophy of doing well by doing good. Today, with a distribution network developed and supported by the World Health Organization, the World Bank, the Carter Center, the Gates Foundation, and others, the Mectizan Donation Program reaches more than 250 million people a year. “River blindness is being eliminated,” Vagelos says, with obvious pride.

In 1994, Vagelos stepped down from Merck due to a company rule that CEOs retire at sixty-five. That was the year he was invited to speak at the Rahway High School commencement.

The school had changed since Vagelos’s day. The students were now mostly Latino and Black, many were poor, and few went on to college. The Ivies weren’t even on the radar. Roy and Diana Vagelos talked it over and decided to fund full scholarships at Rahway High for any student who got into a top-tier school.

Kids responded. At least two or three a year became Vagelos Scholars, and Vagelos got to know many of them. That’s how he met Rosa Mendoza ’14PS.

“Rosa!” Vagelos says, lighting up at the name. “She is unbelievable. The impact she has on faculty at Columbia is something like I’ve never seen. Yet she’s very understated. And she’s a wonderful doctor — incredible with patients.”

Like Vagelos, Rosa Mendoza took an unlikely route to Columbia. The youngest of four children, she was born in rural El Salvador in 1986, during a civil war that only worsened the country’s extreme poverty. Her parents were subsistence farmers who grew corn, mangoes, and papayas. Some years, after a dry winter, the family did not have enough corn for tortillas, their main staple.

Mendoza was five when her parents left El Salvador for the industrial town of Linden, New Jersey. She and her siblings stayed behind with their aunt and grandmother while their parents worked in plastics factories and sent money back home. A few years later, it was Mendoza’s turn to go to los Estados Unidos.

“It was tough, because I had gotten so used to my grandmother and my aunt, and I loved them,” she says. “Of course, I loved my parents, too, and I remembered them, but it wasn’t easy to move away. It was scary.”

She didn’t speak English and had to navigate a world completely different from all she had known. The experience forced her to “mature faster than usual,” she says. Between ESL classes and Nancy Drew mysteries, she picked up the language quickly. When she was thirteen, her family bought a house in Rahway.

Mendoza attended Rahway High, where she was an A student who volunteered at the local nursing home. In eleventh grade she was invited to the annual Vagelos Scholars dinner. Two seniors were being honored: one was bound for Princeton, the other for Penn. Just knowing this chance existed gave Mendoza “tremendous hope.” She worked hard and got into Princeton — thirty miles from home, but so much farther than that.

As a Vagelos Scholar, Mendoza majored in molecular biology. In her third year she volunteered as a translator at a local hospital, and that’s when she realized she wanted to be a doctor. She discussed it with Vagelos, who told her to follow her heart — and to keep pushing herself academically. Mendoza did, and in 2010 she got into every medical school she applied to, including Columbia.

Her decision hinged on financial aid: which school could offer the best package? Vagelos ended any suspense. He told Mendoza that if she chose P&S, he would cover her loans, and she could graduate debt-free.

It’s Wednesday at 12:30 p.m., and Mendoza walks the corridors of the Columbia-affiliated Farrell Community Health Center, a tidy two-story primary-care clinic on West 158th Street near Riverside Drive. Mendoza, the attending doctor, commutes from Rahway, where she lives with her husband, Diego, in a second-floor apartment on a quiet street, not far from her parents’ house. As she passes exam rooms and conference areas, the staff greet her with warm smiles.

On this day, Mendoza has seen an eighty-year-old man, an expectant mother, and a transgender teenager. She’ll see more patients and hear presentations from the residents — another thirty cases before she leaves at 6 p.m.

“We in family medicine deal with the bread and butter,” Mendoza says. “Knee pain — you don’t, at least not initially, have to go to an orthopedist for that. An adult with asthma doesn’t necessarily have to follow up with a pulmonologist. We’re over-utilizing specialist services. Nationally, we need to focus on primary care.” She adds, wryly, “But then again, I’m biased.”

Many of Mendoza’s patients suffer from hypertension, diabetes, or asthma. But the clinic sees it all. Mendoza values the variety: she’s a committed generalist, curious about everything, with a special interest in community health and obstetrics.

“With hypertension and asthma, we have to acknowledge the economic stressors and deal with them,” she says. “Family medicine can do that, because it allows us to see the whole family and to look at the social context. We’re really good at context. And that makes patients trust us more, and therefore be better able to manage their problems.”

While family medicine is “one of the most important fields,” Mendoza says, “it is also one of the lowest-paid.” According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, the US will face a shortage of up to forty thousand primary-care doctors by 2030. Mendoza suggests that primary care has become devalued, not only because physicians earn less but also because, unlike cardiology or orthopedics, it does not attract a lot of research-related dollars. She wants to see the field restored and respected as the bulwark it is. “In the long run we end up saving the health-care system money and protecting patients from getting those illnesses that require expensive procedures,” she says.

Mendoza works at the clinic one day a week while completing a two-year research fellowship in community health at Columbia — her area of focus is adolescent birth control — after which she’ll look for a full-time job.

“I do want to stay in academic medicine,” she says. “I want to be a mentor to new doctors and teach them how important community health is. My goal is to find a place where I can teach and also serve patients who are underserved — the people I’m coming from.”

Throughout Mendoza’s career, Vagelos has been a guiding presence. “I would call Dr. Vagelos more than a mentor,” Mendoza says. “Every step of the way when I’ve had to make the biggest decisions, he has been there for me.”

In 2015, the Vageloses were guests at Mendoza’s wedding, held at St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Rahway. The groom’s brother officiated. At the dinner reception, Mendoza’s mother, who spoke little English, went over to the Vageloses and hugged them. Then, as if to express something beyond language, she took their plates to the buffet table and filled them up with food.

In December 2017, Columbia announced that Roy and Diana Vagelos were giving $250 million to Columbia’s medical school. Of that amount, $150 million has gone to an endowed fund to replace all student loans with scholarships, making Columbia’s medical school — renamed the Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, or VP&S — the first debt-free school of medicine in the country.

“The debt taken on by medical students is enormous,” Vagelos says. “As a result, many students, because of their loans, have turned away from less lucrative specialties like primary care, pediatrics, and medical research. If we can change that, I think we’ll have done something impor-tant for these students and, ultimately, for the field of medicine.”

The Vageloses have deep ties to Columbia. As well as supporting scholarships, they were the catalysts behind Columbia University Irving Medical Center’s precision-medicine initiative and the principal contributors to the Roy and Diana Vagelos Education Center, a state-of-the-art glass tower of classrooms, meeting rooms, medical facilities, and clinical-simulation spaces, which opened in 2016. At Barnard, where Diana chairs the Trustee Committee on Campus Life, they funded the Vagelos Computational Science Center, endowed a professorship in chemistry, and built the Diana Center, a 98,000-square-foot hub for student life and the arts.

In addition, they offered a matching challenge to help fund the debt-free medical school, which proved so compelling that it quickly raised $25 million, enabling Columbia to start the program this year. Of nearly seven hundred students enrolled in the medical school, about half qualify for student loans. Going forward, all financial aid will be in the form of scholarships.

Lee Goldman, chief executive of CUIMC and dean of the medical school, says that the problem of med-school debt is often downplayed, since people assume graduates will make a lot of money. “But in medicine,” he says, “you finish four years of school, then you do another three to seven years of internship, residency, and fellowship training, all while your debt is accumulating interest. Then you have to find a career that will allow you to pay those debts.”

While Goldman is pleased that Columbia is the first among its peer schools to replace student loans with scholarships, he hopes it will not be the last. “It would be great if other schools follow us,” he says. [Just before Columbia Magazine went to press, NYU announced its own debt-free initiative.] “We’re not trying to gain some permanent competitive advantage in attracting students; we’re trying to change the field of medicine.”

The Vageloses live in Somerset County, New Jersey. Since 1995, Roy Vagelos has been board chair of the biotech company Regeneron, headquartered sixty miles away in Tarrytown, New York. On the morning of his visit to Rahway, Vagelos got in his silver Lexus and took a drive down memory lane, otherwise known as I-78. He stopped first in Watchung, where he and Diana and the kids had lived when he was at Merck. Feeling nostalgic, he drove by their old house, then continued to Rahway, past Rahway High, where he’d graduated first in the Class of 1947, and over to Campbell Street, where he found a parking spot directly in front of his childhood home, two blocks from the diner.

Vagelos got out of his car and gazed at the gable-roofed house, whose siding is now painted a pale yellow. He walked to Irving Street, to Mr. Apple Pie. No one passing him on the sidewalk would know that this was one of Rahway’s great benefactors, the former head of Merck who had sent hundreds of kids to college, set new standards for corporate philanthropy, and introduced debt-free medical education to the United States. Today he was just a guy on his way to get a bite — which is to say, he was simply himself.

Half an hour after his arrival at Mr. Apple Pie, Vagelos sits in the booth, telling stories. Someone asks him about his time at Merck, noting that while he was CEO, Fortune magazine named Merck the country’s most admired company seven years in a row.

“We were doing things that were magical,” Vagelos says, with that look of youthful, shiny-eyed wonder that often comes over him. “And when you have that magic, you have a responsibility to use it to affect people who have a dire need. You can’t do it for the whole world, because you can’t afford it. You must pick examples and do it big.” It’s a message that applies to everything Vagelos has done, from fighting disease to eradicating student debt. “Don’t showboat,” he says. “Make it real.”

And what about the old restaurant? What happened to Estelle’s after he left for college?

“My dad retired in 1956,” says Vagelos, cutting another bite of pie. “He sold the business to a young couple, but he could not stand not working. So he went back to the restaurant and offered to help out. He worked for a few years until they really got going, and then they didn’t need him anymore. He was in his seventies and took another job as a cashier in a diner a couple of blocks from Merck. When he was eighty, they said, ‘You’ve had enough.’ So he quit and got into gardening.”

Vagelos’s voice softens. “He became a retiree,” he says. “Which is something I’ve not yet accomplished.”

Vision of a debt-free future

“I tell my patients, once you have glaucoma, you have it for life, and I have to see you for the rest of your life,” says David Solá-Del Valle ’11PS, an ophthalmologist at Massachusetts General Hospital. “That means doctor and patient have to click. I love reaching that point: getting to know the family, practically becoming part of the family over the years.”

For Solá-Del Valle, it all started the day in 2007, during his second year at P&S, when he was called to the financial-aid office. The summons terrified him. Had he defaulted on his loans?

He approached the office with dread. When he got there, he was handed a letter, which said that Dr. P. Roy Vagelos had paid off all his loans. His medical training was now debt-free.

Standing there, Solá-Del Valle began to cry.

He called his mother in Puerto Rico. Solá-Del Valle’s parents had divorced when he was four, and he grew up with his mother in Caguas, twenty miles south of San Juan. The median income of Caguas is $24,000, with a poverty rate of 37 percent, but Solá-Del Valle had always dreamed of being a doctor. He excelled in high school and rode a full scholarship to Harvard, where he graduated magna cum laude. When he got into P&S, he agreed to take the $200,000 plunge (the average debt per student for the Class of 2018 was $190,000). His mother worried that it would be years before he could have a good life.

The Vagelos letter changed that. Solá-Del Valle entered his third-year rotations lighter of spirit. “I had freedom: money was truly not an issue. I knew that no matter what I did, I wouldn’t have debt.”

He began shadowing doctors. One of them was Scott Smith, a glaucoma specialist. As soon as Solá-Del Valle entered the operating room and saw the lasers, he was hooked.

Glaucoma is hardly the most remunerative field, but Solá-Del Valle didn’t mind.

“I could have done refractive surgery to make a lot of money, and maybe I would have had to do that if not for Dr. Vagelos,” he says. “Instead, I was able to choose something I love.”