At the time of Barack Obama’s last Columbia graduation, Ronald Reagan was president, Harold Washington had just become the first black mayor of Chicago, and the gates at 116th Street and Broadway were wide open. On Low Plaza, Obama’s all-male class, the last in College history, watched as philosopher Mortimer Adler ’28GSAS received an honorary degree, six decades after failing to get his BA because he didn’t pass the swimming test.

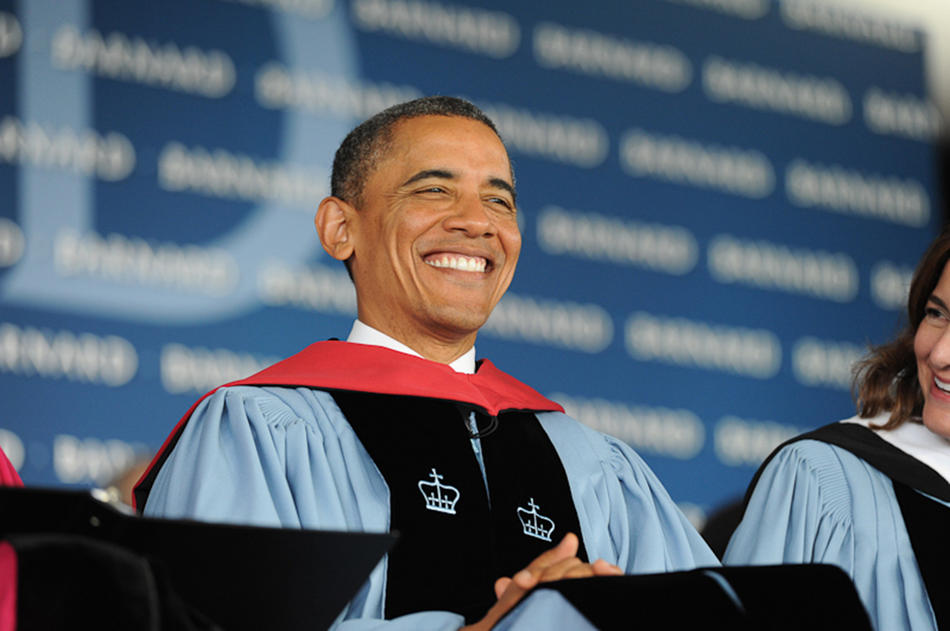

Fast-forward twenty-nine years, to May 14, 2012. The iron gates were locked and blockaded by three garbage trucks. Campus buildings were evacuated and sealed. Magnetometers and Secret Service agents were everywhere. And on South Lawn, under a white tent, thousands waited to hear Obama speak as president of the United States.

Obama’s Commencement address to the Barnard College Class of 2012 had been much gossiped about. An official White House statement said that “as the father of two daughters, President Obama wanted to speak to some of America’s next generation of women leaders.” But pundits concluded that the Barnard overture was part of the president’s effort to shore up his female base in an election year.

“Today, women are not just half this country; you’re half its workforce,” Obama told the 594 cheering seniors, their families, and their friends. “More and more women are outearning their husbands. You’re more than half of our college graduates and master’s graduates and PhDs. So you’ve got us outnumbered.”

For those who know Obama not just as the leader of the free world but as a member of the Class of ’83, his appearance on South Lawn seemed improbable. It’s hardly a state secret that the president has never fully embraced Alma Mater.

“He felt no attachment to Columbia,” writes journalist David Maraniss in the newly published Barack Obama: The Story. Obama himself has acknowledged that as a transfer student from Occidental College, where he spent his first two undergraduate years, he wasn’t a man about campus.

“Mostly, my years at Columbia were an intense period of study,” he told Columbia College Today in 2005. “When I transferred, I decided to buckle down and get serious. I spent a lot of time in the library. I didn’t socialize that much. I was like a monk.” His classmate Wayne Root, the 2008 Libertarian Party vice presidential candidate, told the New York Times shortly before the election, “I’ve not only not met him, I’ve not met anybody who met him.”

Still, Obama wasn’t entirely reclusive (“This area looks familiar,” he quipped from the podium). He hit the local landmarks periodically, eating at Tom’s Restaurant with his roommate and fellow Occidental transfer student Phil Boerner ’84CC and listening to jazz at the West End. He had some minor involvement with the Black Students Organization. And he published a long piece about two student antiwar groups in the campus newsmagazine Sundial.

But like many of his classmates, Obama struggled to cope with the fierce New York of those days. The College didn’t offer dorm rooms to transfer students back then, and, as Obama told the Barnard graduates, “some of the streets around here were not quite so inviting.” In a now-famous story, the twenty-year-old future president couldn’t get into his walkup apartment at 142 West 109th Street on his first night in Manhattan. By his account in his memoir Dreams from My Father, he slept in an alley and bathed at a fire hydrant with a vagrant the next morning. Later, when living at 339 East 94th Street, he would talk with neighbors about the sound of gunfire in the night.

Now, in his return to Morningside Heights, sniping broke out again, this time of the verbal variety. Some Columbia students took the news of Obama’s impending Barnard address as a snub. (It didn’t help that the College Class of 2011 had tried unsuccessfully to persuade the president to speak at Class Day the year before.) The Spectator and Bwog were flooded with responses of disbelief and anger. Curiously, though Barnard did not solicit the speech, it took the brunt of the attack. “Academically inferior” and “feminazis” were among the milder epithets.

Barnard president Debora Spar dismissed the invective as “nineteen-year-olds writing at four thirty in the morning.” And by the time Obama spoke, the conflict had evaporated amid the joy of graduation. The president got plenty of laughs when he referred to the “sibling rivalry” of the occasion — perhaps a nod, in part, to his sister, Maya Soetoro-Ng ’93BC.

“I can tell you that he has affection and respect for Columbia and the College,” said Federal Communications Commission chairman Julius Genachowski ’85CC, Obama’s Harvard Law School classmate and Harvard Law Review colleague. Indeed, though Obama couldn’t make his twenty-fifth reunion, which coincided with the 2008 presidential campaign, the then senator from Illinois gave Columbia a thousand dollars and sent a warm note to his class.

Would he attend his thirtieth next year? Obama’s classmate Jonathan Zimmerman, director of the History of Education Program at New York University, who remembers the president from a sociology class taught by Andrew Walder, hopes so. “I’ve never been to a reunion,” he said. “But if that guy says he’s going, I’m going!” More likely, the Columbia College Alumni Association will at some point give Obama its highest honor, the Alexander Hamilton Medal: the presidency aside, the CCAA has presented the Hamilton to every other College graduate who has won the Nobel Prize.

“I think that after things settle down, he would be open to it,” said Gerald Sherwin ’55CC, co-chair of the CCAA’s Alumni Recognition Committee. But then, Sherwin asked, what do you give the man who has everything? “An honorary degree? He already has a Columbia degree. I’m sure he passed the swimming test.”