When I was twelve, I got sold to a couple in Hsinchu. My husband used to say, before he died, that my father sold me because I complained too much. But that’s not true. It was my fate.

I think of this as I open the door to find my daughter, Chio-Kwat, standing on the doorstep, smoothing her hair behind her ear, her head bent down. Behind her is Taoyuan’s biggest street, with rickshaws clattering, motorcycles zigzagging, cars crammed from curb to curb. But I know my daughter has walked here in her canvas shoes, her delicate nostrils filtering the must and fumes. Her eyelashes twitch, casting shadows on her cheekbones, which are like mine — too pointy, bad luck. She needs to eat more, to gain more weight like me to soften the angle of those bones.

Her pale skin, also from me, is tight and smooth. She hasn’t cried much over her father’s death. She must have come for the money.

“Have you eaten?” I say. For this is how we greet each other in Taiwan.

“Yes, I had breakfast,” she says, moderately polite. It is noon. She’s obviously come expecting lunch and she looks to the side in embarrassment, her eyes flickering over the shiny rosewood of my altar and side table. “I was just at the market so I thought I would visit.”

Her hands are empty, but it is entirely possible that she was unable to afford anything at the market. She spends all her days in a shack with a corrugated tin roof, stringing umbrellas together by hand with her good-for-nothing husband. I let her in. She is, after all, my daughter, though she was supposed to have forgotten about that.

I serve her sparerib soup and bean thread noodles with pork. I have become Buddhist, a vegetarian, but I still cook meat at home every day to serve my lazy son and his conniving wife. I know, you see, what they’re up to.

“How is my brother?” Chio-Kwat says, and her words jolt me from thinking about the envelope in my pocket.

“Hmm. Still losing jobs. Now he’s in a cannery.”

She eats two bowls of noodles and seven pieces of sparerib. “Ay! When did you last eat?”

Her face sours. “Breakfast, I already told you.”

She is the only person I know who complains more than me. When she was a girl I passed her house on my way to the market, and even then, standing in the doorway, she would look at me with those greedy eyes, trying to make me feel guilty. I just thought, it’s a good thing we gave her away when she was born. Give her five dumplings, she’ll want ten. We would have had to pay dowry, too.

So, you see, she was supposed to remain their daughter, marry their son. And if she had, she would have been better off. Their son she was supposed to marry went to college and wears shirts imported from Japan. He rides a Suzuki and bought a new house, three stories, bigger than mine. Instead, Chio-Kwat knocked on my door when she was sixteen. Unknotted her bundle of clothes on my futon. Complaining, complaining. Her mother beat her, her mother called her names. And so? So she ran away and came back to us. So she married for love, and now she has a husband, poor and beating her every day. Probably beating her with those umbrellas. She could have been wearing nice Japanese clothes like that boy.

I take her up to the roof so I can water my plants. I catch my breath, my cheong sam too tight around my belly. She sits down on a folding chair, smoothes her hair behind her ear. She’s waiting. Waiting for the money. She breathes as hard as me, though she shouldn’t, being so young. Maybe she’s anticipating. My husband, on his deathbed, promised her a house. I see her glance at the table, where there are loose 10NT bills.

“I’m bringing those to temple,” I say. I scoop up the bills and put them in my pocket next to the envelope. I need that money to buy candles.

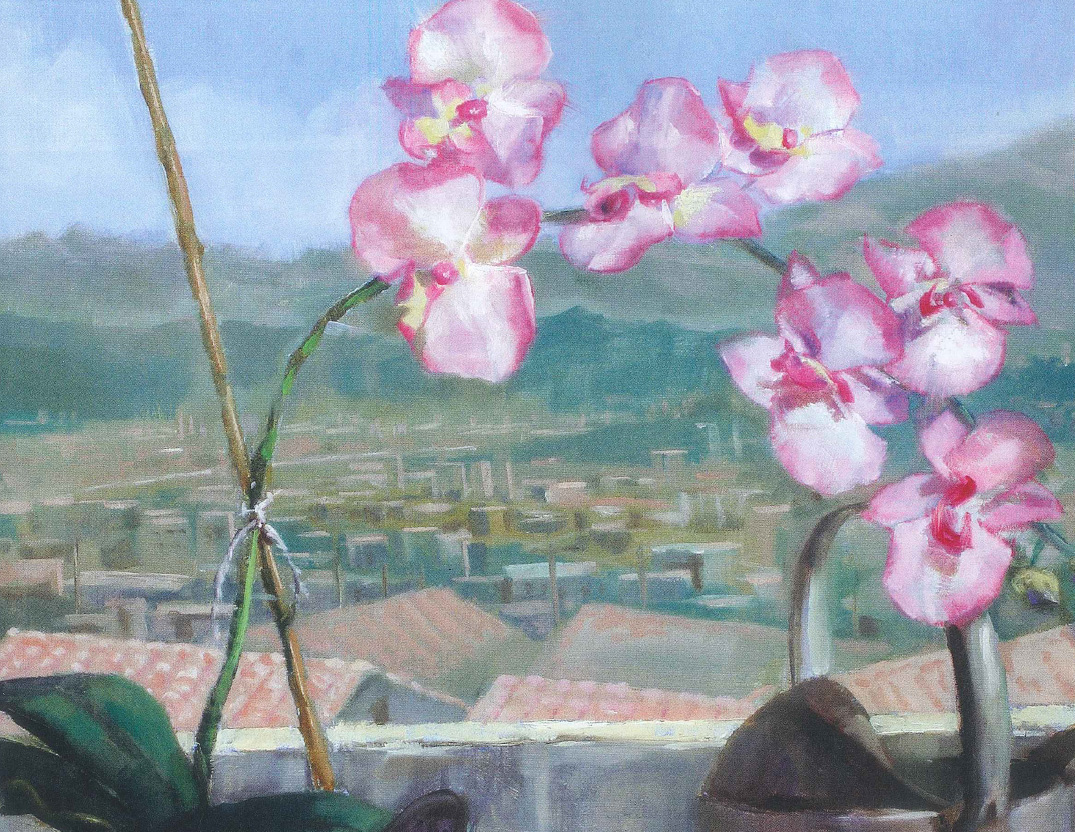

I water my orchids. I have placed them on the south side of the building, the best light for orchids, so as I water I face the Central Mountains, far off, where I was born. I can hardly see the green peaks anymore because of my cataracts, but as I water — just a little, for too much water will drown an orchid — I can smell the thick pine forest, the moss from Chia-Yi, where I have not set foot for sixty years.

Across the street there’s a tall building with a peeling poster of the Democratic Progressive Party candidate — the one who’s going to get us attacked, talking about independence from China. Before the building was built, I could see all the way to the Taiwan Strait. It was there, the west coast, where I was taken by horse cart, to the couple who bought me and trained me to keep their Japanese-style house sparkling clean, their altar polished.

“You were not lucky,” I say to Chio-Kwat. “I did not know, when we gave you away, that your new parents would be so unreliable.” They said they were teachers. And they were, but in music; they were Chinese opera singers, moody and broke.

“You could have asked,” Chio-Kwat says, frowning.

“Do not be insolent.”

This is her problem. Always complaining. Never accepting.

“I am not insolent,” she says. “I am just saying, you could have asked them.”

“It was your fate,” I say. She doesn’t know I had no say in the matter. It was my in-laws who decided she would be given away. And seeing how ungrateful she is, I bring out the envelope from my pocket and unfold the document. My son has written it, as I was busy being a maid and did not learn these fancy words. I hand Chio-Kwat a pen.

She squints at the paper. “What do these words mean?”

Well, she didn’t go to school much, either.

“Sign it, and you say you don’t have any right to the inheritance.”

Her face darkens. “My brother.”

It’s true. My son is a snake. My daughter-in-law is the snake charmer. But it is better to keep the money in the family. Chio-Kwat’s husband will gamble away everything or spend it on his girlfriends.

“We took you back,” I say, “and we had to pay a lot of money to those people because you left. Just after the store closed, too,” I add. “We had no money to spare.”

She drops the document on the floor and stands up. She folds her arms. It’s like the day she came home, jutting her chin out. “I won’t sign it.”

I feel a rush of anger. “Then you are no longer my daughter.”

She stands for a few minutes, looking away, blinking. She turns to the south, the wind blowing the hair off her forehead. Perhaps she is thinking about lawyers, which she cannot afford and which are a joke anyway.

She turns back and kneels down on the concrete floor to sign. As she bends over the paper, I gasp, seeing the fullness of her breasts filling the neckline of her dress, the curve of her belly. Now I know why she was so out of breath.

She throws the pen on the floor and stands up, eyes flashing. She sees my open mouth and traces my gaze to her belly.

“Ma,” she says. “I came here to tell you.”

I’m wordless for a moment, listening to the wind, to the honking of cars and the clattering of rickshaws in the street below.

She turns to leave.

“Wait,” I say. And I pull the temple money out of my pocket. “For the baby. For good luck.”

She hesitates, frowning, then grabs the money out of my hand.

She leaves, and the wind slams the door behind her. The air rises, swirling around me, and the document flutters against my legs. In the wind I smell Chia-Yi.