The day unfolds to a different rhythm when you come this far east in India. A gray light seeps across the sky at around this time, a quarter past five in the morning, bringing back the simple shapes of things. I have the illusion, standing up here on the verandah, peering at the trees that are inky silhouettes and the wild shrubs that are black walls blurred with mist, that I’m seeing the earth as it was in the beginning: dark, peaceful, and absolutely still. Coming to Assam, I feel like I’ve migrated to another country, though this is still India. This is the same country I was born in, just the opposite end of it, two thousand miles from Punjab. The blue hills of Burma stand on the horizon, and there’s a touch of China in people’s faces, in their eyes. Yet everything seems far away, the noises of the world muffled by the forest.

This is the time of day I like best, the air soft and cool, free of the dirty whiffs of petrol and tar the evening breeze carries, especially when you’re down in the market near the refinery. The other day, as I stood here having a beer after office, a flashing cloud of flame appeared in the distance, behind the rain tree that rises up on the hill across the road. For a moment I thought it was a view of the chimney I can see from the General Office, the gold flame so much bigger that I was afraid a fire had broken out in the refinery. It took me a moment to realize it was a trick of light, the glare of the setting sun splintering and flickering through the sprawl of tree limbs, not a blaze of oil and gas. We chase the sun with our timings here, trying to capture the most light, our clocks turned an hour ahead of the rest of the country. Normally I’ve had my bed tea by now, since office starts promptly at 6:00 a.m.

Since I’m one of the few Indians who owns a car, privileged with a company loan, it’s only a few minutes’ drive back. Some of the older engineers and scientists, the ones who started at Assam Petroleum before independence, when the British called them “Indian assistants,” show a slight resentment toward me. They joke about my staying in the British settlement in the hills, looking down on ordinary mortals like them on the plain. Many of them live in cottages around the oil field and get around town on bicycles. Though the refinery operates around the clock, the General Office closes at 3:00 p.m., since my British colleagues like to end the day on the golf course or tennis courts. Many of us younger Indian managers like to join them on the sports field — I enjoy a game of squash at the club — so it was troubling to hear of a sign posted outside the Digboi Club right up to 1947, eleven years ago, when we won independence: “INDIANS AND DOGS NOT ALLOWED.”

Someone pulls and scrapes a door latch behind me. My housemate Varinder steps out of his bedroom, already dressed in a shirt and tie. He raises his head abruptly, not expecting to find me here in the dark. “What happened to him? Why hasn’t he brought the tea till now?”

“Three times I’ve called down, but there’s been no reply,” I tell him, feeling annoyed again that no one has come to explain the delay, neither the bearer, Suraj Ali, nor the cook or the other two houseboys.

Varinder snaps open the tin of Three Castles in his hand, offers me a cigarette. Though I’ve done my shave, too, waiting for the tea to be brought up, I feel untidy beside him in my crumpled pajamakurta. We’re both at the General Office, Varinder in administration, around the corner from accounts.

Walking across the wide verandah to the back staircase, he calls down in a tone of easy command, “Suraj Ali! Chalo, Suraj Ali, chai lao!” Suraj Ali, bring the tea! Varinder continues gazing down the back stairway the servants use to carry things up from the kitchen, which occupies a separate shed in the rear of the garden. He turns to me with a look of dismay. “He must have gotten drunk last night. Must be passed out in his room.”

A shrill whooping shears the silence, startling both of us. Varinder spots it first, joining me at the verandah rail. “It’s there — in the pomelo.”

I shift my gaze to the tree by the gate. The sky has paled some. In the masses of clustered black leaves I see the shadow of a hornbill before it launches itself in the air. The sweep of its beak rises as its body springs upward. “Oh, yes,” I say. It’s a rare bird to catch sight of. I’ve seen it only two or three times in the sixteen months I’ve been in Digboi. The tribals hunt it for its spectacular beak, with which they decorate their hats. Varinder has suggested a trip down to the Naga villages. I’d like to make a group and just travel somewhere for the weekend, the way we did a few months back, piling into two cars and driving up the Ledo Road through steep mountains all the way to the Burma border. But the two longer holidays I’ve taken since I joined the Assam Petroleum Company were both spent in Delhi, seeing my parents.

I remain standing at the rail after Varinder goes inside, fed up with the servant’s lack of response. A cycle rattles clumsily up the road, making a loud clicking noise as it passes the house, and I begin to feel impatient again. I still have to take a bath, send my shoes down for polishing. The siren will go off at five thirty, warning there’s half an hour left till office starts. Everybody up! Eight times a day the hooter wails, marking shift changes at the refinery and the General Office hours. Is Suraj in such a stupor he can’t hear the deer now barking in the forest like quarreling dogs? I walk across the dusty floor and shout down the back stairs, “Suraj Ali! Suraj! Kya hogaya, bhai?” What’s going on?

A couple of minutes later Suraj Ali finally appears in khaki pants and sweater vest, carrying a large wooden tray with both arms tensed. Cautiously he mounts the steps in his ragged slippers. A tall, embroidered cozy shields the teapot.

“What happened to you today? Why did it get so late?” He doesn’t answer me, so I continue scolding him, “I’ve called down so many times. None of you came up to say anything.”

Suraj Ali sets the tray down on the cane table, pushes the ashtray away, and greets me with his head tilted lower than usual. “Guha Sahib’s servant came to talk to us,” he finally says. Guha, a senior marketing manager, lives down the main road. “He said a big crowd is gathering; they’re going to bungalow 18. He kept telling us to join them, but we didn’t want to get involved. I told him I’m not even a Hindu — the Sahib there killed a cow.” Bungalow 18 is half a mile up the secluded lane of houses that terminates at our drive. Two bungalows and a small forested patch of land separate us from no. 18.

“What happened there?”

“The Sahib shot a cow.”

“What?” I keep my eyes fixed on him. Who would shoot a cow? For what reason?

“He shot a cow that entered his compound last night. The English Sahib. Now everyone wants to go to his house and confront him. They’re feeling very angry — very bad.” Yesterday evening, as he was cleaning the kitchen after all the servants had eaten, Suraj Ali says, he heard several blasts. They seemed to come from far away, making him think someone was on a night shoot in the forest. The hooter erupts in a long, sharp cry. Suraj Ali pauses, looking away to the road, then goes on, saying the others heard the shots, too, but no one knew what they meant. It turns out the English Sahib in bungalow 18 had several servants, all Hindus, who saw exactly what happened, according to Guha’s servant. They gathered up their families and ran out of the compound, telling people along the road their Sahib had killed a cow, the word spreading down the labor lines, to the workers’ quarters near the refinery. “Everyone is coming to know, Sahib,” Suraj Ali insists. “They’re going to punish him for what he’s done.”

Reggie Platt is in bungalow 18 — R. H. Platt. He’s listed on a board at the club as winner of a tennis tournament some years back. The in-charge at the crude-oil distillation unit, I believe. We have a nodding acquaintance. He’s a technical man, so we don’t move in the same circles. I was at the club for picture night yesterday — there was no word of the incident there. I don’t understand why Platt would shoot a cow. Surely he knows the cow is venerated by us. He’s a stern sort of man — that was the impression I had. You’d expect such a man to respect rules and norms.

“The cow wandered into the lawn,” Suraj Ali says in a hollow tone. He concentrates on the floor with a look of dismay, though he’s a Muslim and the shooting cannot feel as hurtful to him as it does to a Hindu servant. To any Hindu. Even to me. “He started shouting at it to get out, and before his servants could shoo it away with a stick, he brought his rifle and began firing from high up in the balcony. They couldn’t even run out to rescue it, because he was in such a temper they were afraid he’d shoot them.” As Suraj Ali tells it, I don’t know how to understand Platt’s action — it seems deliberate. A taunting of his servants, who looked on helplessly.

I’m running late today, which I deplore. Less than fifteen minutes till office starts. Usually I like to reach there ten minutes early. I climb down the outer stairs to the dining room — bathed, dressed, shoes hurriedly buffed by Suraj Ali. We stay in a Chang bungalow, a wooden house raised on pillars, about ten feet off the ground, in the Assamese style. Elevation protects us from rainy-season floods and, it’s said, wild animals. We did once have an elephant and her calf, who strayed out from the forest and plodded around the garden as we watched from the windows. Halfway down the steps, I pause, hearing shouting in the distance. I study the road as it bends around the house, curving away from view, trying to follow the sound. Vague cries, as if people are calling out to each other. I lean over to look as far down the Margherita Road as I can. Now I hear what sounds like wailing, and a shorter, pulsing cry — a chant — but that could be a bird.

Varinder is cutting into a grilled tomato with his fork at the table. The dining room is windowless, painted bright pink, the only room under the main floor of the house. As Suraj Ali sets down a plate of toast in front of our other housemate, Romen, a geologist, I ask him if he’s heard the shouting outside.

“Must be those people going to see the Sahib,” the servant mutters. He hangs back by the pantry door, waiting to hear what we have to say about it.

I remain standing and tell Romen and Varinder about the shooting. Last night Varinder and I went to see From Here to Eternity at the club, then had a drink at the bar. It was 11:00 by the time we got home. “I’ll stop by his place and tell him there can be some trouble if he doesn’t apologize to them.”

“Never mind. Let him sort it out himself — foolish man,” Varinder says stiffly. Switching to Punjabi, he urges me, “Sit down, Teji. Have your breakfast.”

“I came back around 10:15 from Shyam’s place,” Romen says, squinting behind his glasses. “One bad hand after the other.” He has a fondness for cards, like me. “I didn’t hear anything. Everything looked normal.”

“Sit down, Teji,” Varinder says.

“I’m going to talk to him,” I reply. If a crowd of poor men feel injured and angry enough, there’s no telling how they might vent their frustrations. An Englishman like Platt who moves between the club and the refinery has little idea of how easily people’s sentiments can be crushed.

“I’ve seen him knocking back one peg after another at the bar,” says Romen. “Quite a boozer.”

I go out to my car. It’s a secondhand black Landmaster without a scratch on it, gleaming wet from a quick wash by one of the houseboys. There’s five lakhs of cash packed in a steel trunk in the boot that has to be delivered to the company cashier. Yesterday I went out to Dibrugarh to meet our local banker, a Marwari moneylender, Kanhaiya Lal Aggarwala, who distributes cash to tea estates throughout Upper Assam on behalf of the big Calcutta banks like Grindlays and Lloyds. Since I was there, I brought back the company’s weekly funds myself rather than have his driver deliver it to us later in the week. Last night, I parked the car at the club, still full of the money. This is a safe place — people are very honest. They’re good people. Every Friday the banker’s car makes the trip through the forest to our General Office, and though the villagers along the way recognize Kanhaiya Lal Aggarwala’s Studebaker, probably aware it’s transporting a large amount of cash, there’s never been an incident.

As I drive up the lane, I hear shouting — it sounds far away, a muffled echo of words. I don’t see anyone on the road below. The bungalows perch along a ridge above the main road, screened by a thick netting of branches and brush. Bungalow 18 is set a short distance back from the lane. Platt’s lawn is bigger than ours — it must be a two-acre lot — a hedge of spindly purplish plants outlining the perimeter of the lawn.

I stop behind his car, which is parked in the vacant space underneath the house. Platt’s bungalow is a close replica of ours, the same wide sloping roof of corrugated iron and rows of slender pillars lifting the structure off the ground. Near the outer stairs, where at our house we have clusters of clay pots, a narrow bed is planted with dahlias tied to stakes and showy orange flowers, black in the middle. Off to the distance on the right-hand side, banana trees fringe a hillock where the servants’ brick sheds stand, one end of the buildings closed off by screens of slatted bamboo. It seems deserted up there, not even a child wandering about. I turn to climb the stairs to the verandah. On the other side of the drive, at the far edge, where the lawn gives way to rambling wild growth and the darkness of hanging trees, crows squawk around something I can’t make out.

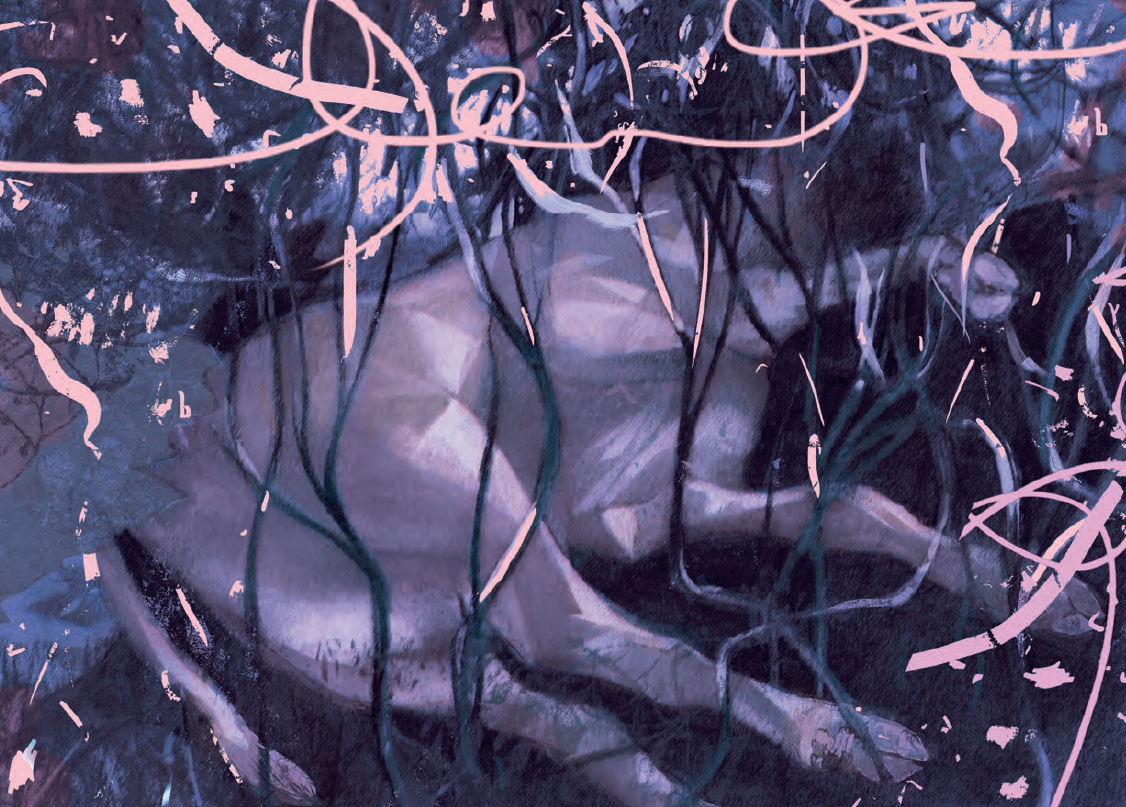

I walk quickly toward the excited birds. The hindquarters of a sprawled animal become visible to me in a swath of frilly weeds, the leaping undergrowth shaded by branches. I’ve never seen a cow lying like this, on its side, with its thin legs thrown out beneath it. I’ve only seen cows sitting up, their heads straight in the air, their feet tucked under their bodies. Now I notice patches of blood darkening the ground like smeared mud. The back legs and tail are washed in blood, too, not mud, though streaks of gray mud, or maybe it’s only dark fur, stain the legs above the hooves. It’s a young animal, slender and delicate. Blood seems to have poured from its anus, or perhaps there was a bullet to the side it’s lying on. I see no hole, no wound in its flank. Birds are walking over the calf’s narrow frame, perching on its thin legs bent sharply at the knees. They caw and scatter as I fling my arms, stepping around a puddle of bright blood.

Dark trickles have seeped down its neck, into the soft woolly white fur of its chest. I still can’t make out where it’s been shot. Its head is swallowed by a dip in the ground, a crevice filled with a gust of tall white-flowering weeds and saplings. I step closer and part the greenery. One long beautiful eye is open. Behind it, the ear is gone and the back of the head torn off. The smell is thick and raw. I can’t understand how the eye can look so lovely against the ear stub and splintered red cavity of the skull. A crow lands on its neck, pecking inside the skull’s pulpy bowl. I shut my eyes and look away. My throat feels like someone’s caught hold of it. I don’t have anything to say to Reggie Platt. I owe him no warning.

And yet I walk back to the house, noticing spurs of blood coming from a different area of the lawn, where the cow might have run from. My feet go mechanically up the outer stairs. I don’t know the reason for what happened. A dark shoe print marks several steps. Whether it is blood or slush is not clear — it’s a brown imprint visible on varnished wood. Let him explain himself — although Romen could be right. Platt may have been drinking. Nothing more to it than that. But even then, how could he lose his mind like this? Why slaughter an innocent animal?

The same company-issued cane sofas and chairs as ours form a grouping on the verandah, Platt’s furniture painted white as if a feminine touch has been applied. I remember hearing, though, that he’s divorced — or widowed. The wife, I’m quite sure, is gone. His children are in England or Shillong, some boarding school. He lives alone, from what I remember. Not a sound coming from the house. I knock again, harder. I wonder if he’s already gone — if someone alerted him and came by to pick him up.

A Nepali boy pulls away the curtains from the glass panes and opens the doors. He is wearing a white suit and nods at me shyly. “Where’s your Sahib?” I say. “Tell him Saigal Sahib has come to see him.” I’m led inside to the drawing room. I can see an end of the dining table in the room to the right where the boy disappears. A light is on. Platt must be taking his breakfast. I hear the Englishman’s voice break out sharply, as though admonishing the boy, “Tell him to wait.” I get up, a fury stirring in me, and I cannot stop myself from crossing the drawing room and walking straight into the other room.

“Good morning, Reggie. I wanted to have a word with you.” I stand at the opposite side of the table, near the doorway. I’m taken aback — there’s a young lady seated with him, a dark-haired girl of sixteen or seventeen with wide gray eyes. He introduces her as his daughter, Emily, but says nothing more. I give her a quick smile, wondering what brought her home — I don’t think there are any school holidays in early October. She’s in a housecoat, yellow roses around the collar. She focuses on her plate as if to absent herself. I’m a little uncomfortable bringing this up in front of her, but Reggie is peering at me as if I better explain myself, so I look straight at him and say, “My bearer just informed me that your servants, and some of the servants around, and local people are upset because a cow was shot by you. I just saw it over there, lying under the trees. I think quite a large group may be coming up to you. I heard something on the road earlier —”

He stands up. “All right. Thank you for letting me know.” Around the table he comes to usher me out, apparently not wanting to continue the conversation in the girl’s presence. It was my mistake to burst into the room as I did — I had no idea he had a young daughter at home. Platt is wearing khaki half-pants, knee socks, brown leather shoes. The schoolboy dress of the British engineer. Perfectly bald at the top of the head, thick dark hair at the sides. His eyes are firm under fraying eyebrows that push together.

“There could be a lot of trouble if they see the cow lying there like that — it would be best for you to offer an apology. I’m sure you must be aware we Hindus consider the cow sacred. Gow mata, we call it, because it gives milk just like the mother. Gow is cow. Mata, mother. I can speak to them for you.” I don’t mean it as an offer, and he recognizes that. I mean it as an obligation. Something he must do for the terrible offense he’s committed. Surely he wants to make amends for hurting people so deeply, especially in front of his daughter. Yet coming closer to him in the darkened drawing room, with the door shut to the outside, his brusque, unyielding manner is more pronounced. I’m sure he’s done it deliberately. Maybe he wasn’t even drinking.

“Apologize to who? The bloody servants who come running even when you call ‘Dog’?” Platt pierces me with a look as if I’m some clerk who’s dared to point out a mistake in the Sahib’s work and needs a dressing-down. He better mind how he’s talking, I’m tempted to tell him. I’ll lodge a complaint with administration. I’m a covenanted officer like him. A chartered accountant, responsible for all Assam Petroleum’s cash reserves. The company has only two other qualified chartered accountants: Evans, from the London office, and A. N. Birchenough, head of the finance department, to whom my boss, Mr. Kamble, reports. I’m the only Indian with that qualification. I oversee the payroll of seven thousand workers. Out of a hundred people in the accounts hall, I’m one of five managers with a private office.

“Everyone has strong sentiments about their beliefs, Reggie. Don’t let this thing build up,” I force myself to say calmly.

Beneath a harsh stare, a bewildered expression comes across Platt’s face. Something like puzzlement breaks through, despite his effort to appear in charge. He erupts in a grunting laugh, as if it were all meant in fun. I wonder if he might be drunk now, the way his face reddens and his voice sharpens into mockery. “There’s always a pack of them at my heels. Should I say ‘sorry’ now over a stray cow? Yeah?” His words are knotted up; his sentences twist off and break. He doesn’t speak in sharp lines like the Britishers at the General Office. Unpolished — you can hear it in his voice. “Should’ve started praying? Yeah?”

Maybe it’s that I’m a good fifteen years younger and unapologetic about confronting him that infuriates him. Or does he think of me as some kind of “Indian assistant” from the old days? In a way, he’s trying to tell me he could call me “Dog,” too, if he wanted, and what could I do about it? “As you like. It’s up to you.” I walk toward the door. A ruthless fellow. No point trying to find a reason for what he’s done. There can be no reason. Still, at the door, I call back to him and can’t help the quiver in my voice, “Why did you shoot it? It was just a calf.”

“Any idea how bright a full moon is? You could see shadows on the grass, it was that bright. Couldn’t claim, could I, it was just blind shots in the dark?” He mumbles something I can’t make out. “Teach them not to let their animals roam, making a mess on others’ property. They ought to have put up a pound on this side as well.”

I decide not to speak of the incident with anyone at the office. Platt’s use of the word “property” surprised me. Does he think his bungalow is his property? Not even the general manager’s no. 1 bungalow is his own. It is all company property, company furniture, company servants. The company can take any of it away, at any time. Does he think he’s some kind of proprietor here by virtue of being a Britisher working for a British firm that owns the town? The company has set up a cattle pound out by the oilfields, I remember, near the War Graves Cemetery. That’s what he’d been talking about. Wandering cows were rounded up and imprisoned there. The owner had to pay a fine to get his animal back. Everything comes under the company’s regulations, even a poor man’s cow. I think Platt just wanted to show his servants what he could do to them in their own country. Kill a cow for sport. Mock their beliefs.

But they’d returned, I found out when I went home for lunch that day. The crowd I thought I’d heard down the road in the morning must have reached Platt’s house fifteen or twenty minutes after I left. Normally he would have been at the refinery by then, but he’d stayed back, perhaps for his daughter’s sake.

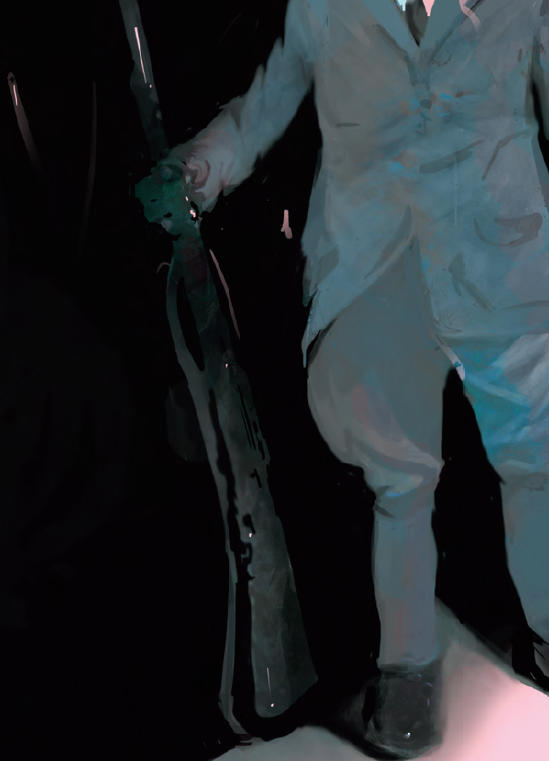

The mob had set fire to his car because at first he wouldn’t come out and listen to them, and when he did, he started shouting. It’s the one thing they hate, being shouted at by any Sahib, and they’d reacted violently, cursing him, igniting his car. Platt went inside and reappeared on the verandah, raising his rifle. That’s when they tried to torch his bungalow, too, Suraj Ali had heard, dousing the stilts with petrol. But Platt had started firing and they ran. From our verandah Suraj Ali had seen dozens of screaming men and even school-age boys bounding down the road, yelling to each other to make sure no one had been hit.

For two days following the incident, I wake up in the mornings seeing the calf with its open, yearning eye. In my mind it is a dying animal, not yet dead because of that eye still seeing the world, all its frenzy, seeing me — an innocent eye that seems aware of everything, accepting of everything. The word in the office is that Maclaren, the general manager, a fair-minded man, a man I admire, is sending Platt back to England. It has become a police case because Platt fired into the crowd, so his departure is seen as a solution. Still, an unspoken anxiety seems to grip the British managers. I think it’s a fear that the masses of Hindu laborers may strike or stage a rebellion of some sort.

The third day after the incident, T. A. B. Skene, our head of staff, comes to my office. After a few questions about an upcoming visit by officials of the Ministry of Natural Resources being arranged by my boss, who is in Delhi for talks with the government, he remarks that he heard I tried to intervene with Reggie Platt. He minces no words in telling me the company doesn’t condone Platt’s behavior in the least. It’s unprecedented to have the number-two man in the company sitting in my office. He pushes himself forward in one of the cane chairs set before my desk, a formidable Scot, long legs protruding, arms closed across his stomach.

Trying to fend off shyness, I tell him, perhaps too bluntly, “He fired into the crowd. He could have killed somebody.”

There’s a distinct tightness in Skene’s voice, a resistance, when he replies that Platt never shot at the crowd. He only fired warnings in the air, which people misunderstood. His mouth usually hovers between a smirk and a jutting-open challenge, so you can never gauge his mood, but now he presses his lips together, as if I’ve offended him. His face is like a soldier’s, the wavy silvering hair creamed back with a shine. A full moustache. They panicked, he says — they had no experience of guns. My servant spoke to some people who’d been there, I try to explain, and they felt themselves to be Platt’s target. He was shooting at the men. Skene lets out a long “No,” as if I’ve completely misinterpreted the situation. He was only trying to disperse the crowd. If Platt had meant to hit someone, he wouldn’t have missed all his shots. I don’t argue with him. He’s the senior man. Platt is leaving the day after tomorrow, Skene tells me, scowling slightly, as if that ought to satisfy me.