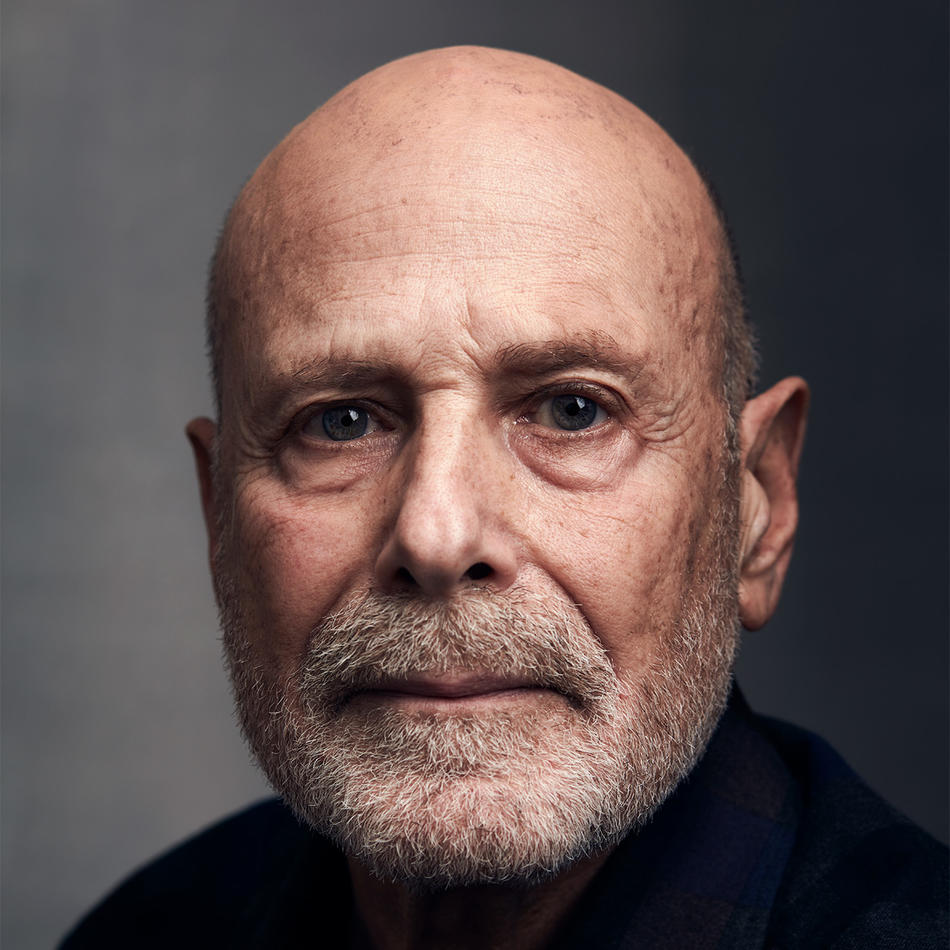

When COVID-19 hit New York and the city shut down, Barry Rosen ’74GSAS took things in stride. People around him grew restless, anxious, and depressed, but Rosen, seventy-six, was unperturbed. “I’m inside a lot, but I can take a walk, I can see grass, I can enjoy the sunshine, I can read anything I want,” says Rosen, who lives on the Upper West Side with his wife, Barbara. “I feel freer than most people who are constrained by COVID because of my experience in Iran. In my 444 days as a hostage, I spent maybe twenty minutes outdoors. I was in darkness most of the time. This is far better than captivity,” he says with a faint chuckle. “Far, far better.”

Rosen was one of sixty-six Americans seized inside the US embassy in Tehran on November 4, 1979. Ultimately, he and fifty-one others would be held in appalling conditions for more than fourteen months. This winter marks the fortieth anniversary of the end of the hostage crisis, but for Rosen the memories are still fresh. Seated in his apartment on Riverside Drive a short walk from Teachers College, where he spent ten years as an administrator, Rosen talks about those horrific 444 days with the disarming openness of a person who has worked for years to make sense of his experience.

As the embassy’s new press attaché, Rosen had arrived in Iran in 1978 full of enthusiasm. He had spent two years in Iran as a Peace Corps volunteer in the 1960s, was fluent in Farsi, and had great affection for the people and culture of Iran. And then came the Iranian Revolution. Fueled by zealous anti-American sentiment, the uprising led directly to the Iran hostage crisis, which destroyed Iran–US relations, battered the American psyche, brought down an American president, and changed the lives of Rosen and the other embassy staff — attachés, officers, and military guards — who got caught in a geopolitical whirlwind.

During his confinement, Rosen suffered beatings, mock executions, and unbearably long, desolate stretches of isolation. He lived in anguish and acute fear, cut off from the world and from his wife and two small children, never knowing if he was going to live or die. When he was finally freed, on January 20, 1981, he had lost forty pounds and much of his spirit.

“Healing has been a very slow process,” he says. “In the beginning I was trying to get my head around it all — especially coming home and trying to integrate into the family and restart my life. It was very hard.” Rosen gradually discovered that what he needed more than anything was to be with people — his family, friends, and colleagues, whose support kept him afloat in rough mental seas. Only after years of therapy, meditation, and reading has Rosen come to understand what happened to him and how to live with it.

Rosen was born in East New York and raised in East Flatbush by his mother, a housewife, and his father, an electrician. Brooklyn was his whole world. Growing up blocks from Ebbets Field, Rosen loved the Dodgers and was heartbroken when they left. He attended Yeshiva Rabbi David Leibowitz in East Flatbush for nine years, graduated in 1961 from Tilden High School, went on to Brooklyn College, and entered a graduate program in public affairs at Syracuse University. His research was on a Pakistani mullah who had formulated a notion of an Islamic state — a kind of forerunner to Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini. Wanting to visit Pakistan, Rosen applied to the Peace Corps, a program started by President Kennedy in 1961 that sent young people abroad to assist in civic-minded projects. But Pakistan was under military rule, and there were no openings. There was, however, an opportunity in Iran.

“It was a chance to see the world,” says Rosen. “The idea of being in the Peace Corps, of helping others, intrigued me, and I really wanted to get out of a more parochial life and the comforts that I had as an American.” Few Americans ever gave Iran a thought, which heightened its appeal for Rosen. He spent three months learning Farsi before flying to Tehran in 1967. He was twenty-three, and it was his second trip on a plane. (The first was to Syracuse.) He loved his Peace Corps duties — teaching Iranian police cadets English, teaching kindergartners at a school near the Caspian Sea — and in his free time he’d leave his small apartment and wander into the bazaar. He reveled in the rhythms of conversation, the long meals, the ancient etiquette. “It was a place where you felt the guest was always paramount,” he says. He made friends easily and felt a thrilling sense of belonging. On holidays he visited historical sites, marveled at the mosques, and lost himself in Persian poetry. When his two years were up and it was time to return to New York, he felt the sadness of leaving home.

Though Rosen never planned to return to Iran, he wanted to pursue Farsi and enrolled in Columbia’s Middle East Languages and Cultures program to study Farsi and Uzbek. One of his professors, Edward Allworth ’59GSAS, a leading scholar of Central Asia, told him after his oral exams that Voice of America (VOA) was seeking a new head of its Uzbek desk. “I wanted to work on my dissertation,” says Rosen. “But I had just gotten married and felt pressure to get a job.”

Rosen worked for four years at VOA. Then, in 1978, his former boss there, who had become the public-affairs officer at the US embassy in Iran, asked Rosen to be the embassy’s press attaché. Going from VOA to the Foreign Service was a huge leap, and Rosen, adventurous and service-minded, embraced the idea. He hadn’t imagined that he’d ever go back to Iran. There was a hint of destiny in it.

Iran, however, was in turmoil: in 1977, Iranians calling for a liberal democracy began confronting the country’s autocratic leader, the shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi ’55HON, over censorship and abuses of the judiciary. The shah had been installed with US support after the CIA backed the overthrow in 1953 of the democratically elected Mohammad Mossadegh (“a brilliant man,” says Rosen), whose desire to nationalize Iran’s oil supply did not sit well with Britain or the US. Now, after twenty-five years, anger against the shah erupted in mass demonstrations. The shah imposed martial law, and on September 8, 1978, known as Black Friday, the military fired on demonstrators, killing dozens.

That same month, the Rosens, living at Barbara’s parents’ house in Brooklyn, had their second child, a girl. They gave her a Persian name: Ariana. Two months later, Rosen left for Tehran. As press attaché, Rosen was spokesperson for the US ambassador to Iran, William Sullivan, and led a staff of Armenian-Iranian and ethnic Persian interpreters who translated articles from the Iranian press. Events were moving quickly. In January 1979, with protests mounting, the shah fled the country, and on February 1, the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, spiritual leader of the opposition, returned to Iran after nearly fifteen years in exile. Rosen had never seen such adulation for a human being as he did among the millions of working-class people who greeted Khomeini’s motorcade as it moved through Tehran.

Two weeks later, in the power vacuum of Iran, armed leftist militants stormed the embassy. Rosen was beaten and thrown up against a wall — he was certain that he would be executed. But forces from Khomeini’s provisional government intervened, the attackers abruptly withdrew, and Rosen escaped further harm. The embassy was closed, and personnel were sent back to the US. Officials reopened the embassy in March and gave the staff the option to return. Many chose not to. Rosen went. The plan was for his family to join him when things settled down.

But conditions grew worse. Rosen knew the embassy was vulnerable, yet through the Tehran spring and summer he pressed on, committed to performing his duties in a volatile environment. The crisis deepened on October 22, 1979, when President Jimmy Carter, bowing to domestic political pressure, allowed the cancer-stricken shah to enter the US for medical care. The reaction in Iran was intense. Outside the embassy, angry students, many of them from traditional middle-class families, burned US flags and effigies of Carter. Rosen, in his office, could hear shouts of Marg bar Amrika! —- Death to America.

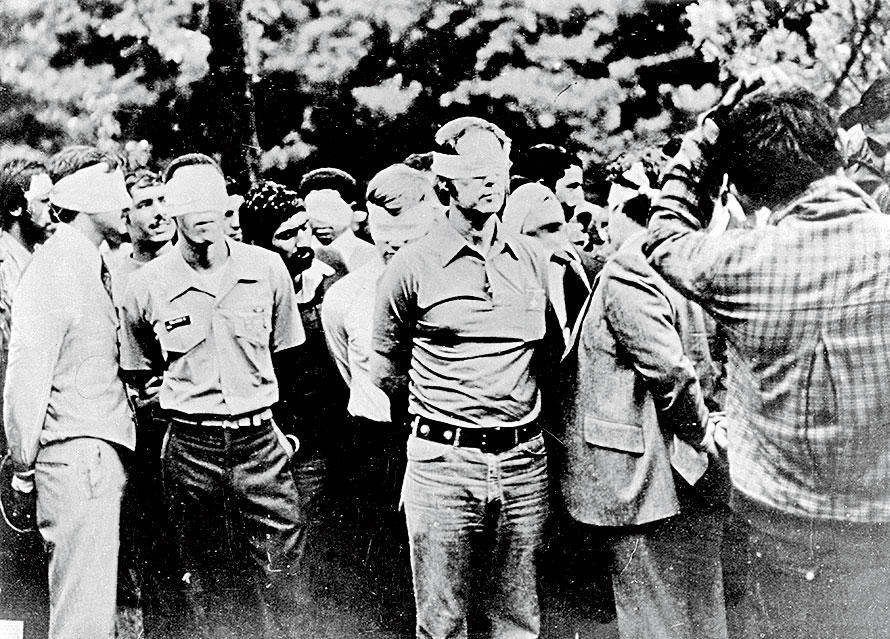

The morning of November 4 was gray and rainy, but the demonstrations continued. Then, from his window, Rosen noticed that the students were climbing over the embassy walls. The next thing he knew, there was pounding at his door. When Rosen’s secretary opened it, the students, who looked more like boys than men to Rosen, poured into the room and accused him of being part of a “nest of spies.”

“I stupidly said, ‘This is the US embassy, and according to the Geneva Accords …’ They threw me down in my chair, tied my hands. Before they led me away I said goodbye to my staff. Everyone was crying. I told the students, ‘Leave these people alone — they have nothing to do with us.’”

Bound and blindfolded, Rosen was detained at first in the kitchen of the ambassador’s quarters. Like the other hostages being kept tied to chairs in dark rooms in the sprawling embassy and watched round the clock, he assumed the ordeal would be over in a few days. But the students had the “Great Satan,” as Khomeini referred to the US, by the tail, and — fearful of American plots and reprisals — they could not let go. For Rosen, the situation was beyond terrifying. “There are no words for it,” he says. The captors held guns to his head and ordered him to sign a confession that he was a spy: he had ten seconds or he’d be shot. Rosen resisted until the last two seconds. After that, he felt utterly broken.

Each night, he tried to stay awake. If you’re up they can’t kill you, he told himself. Stay alert, stay alert. Students would barge into his room to scare him. “They’d point guns and then pull the trigger and there was nothing. It was a psychological game.” Some hostages attempted suicide. One man banged his head repeatedly against a wall. Another tried to cut his wrists with glass. Rosen was not immune. “Every day,” he says, “I wanted to die.” The students controlled when the hostages ate and when they were allowed to use the bathroom, and as the days of hunger, humiliation, and terror dragged on and the unheated embassy got colder and colder, Rosen lapsed into a depression.

That first winter, a delegation of US clergy, including Reverend William Sloane Coffin Jr., senior minister of Riverside Church, traveled to Iran to check on the hostages. Before his departure, Coffin received a visitor at the church: it was Barbara, who handed him a letter and a family photograph. In Tehran, Coffin gave the picture to Rosen. Deeply moved, Rosen did his best to appear cheerful to Coffin. He did not want his family to worry — nothing was more important to him — and when Coffin returned to New York he told Barbara that Rosen was in good spirits.

That was balm for Barbara, but of course she still worried and had to push herself through the countless days. Fortunately, she had help: everyone — her parents, her grandmothers, her siblings, her in-laws — pitched in to care for the kids. “They say it takes a village,” she says, “and I was lucky to have a village.”

In April 1980, Barbara traveled to Europe to rally support for international sanctions on Iran. While she was in Germany meeting with Chancellor Helmut Schmidt, the US staged a rescue mission, but it was aborted when a sandstorm in the Iranian desert disabled the rescue helicopters. One of the grounded helicopters backed up and struck a refueling plane, causing an explosion that killed eight service members.

News of the failed attempt prompted the captors to divide the hostages into groups and send them to different locations around the country. Rosen landed in a windowless cell in what he believes was the city of Isfahan, 250 miles south of Tehran (he saw “Isfahan” written in Farsi on a bottle of milk). His cellmate was Dave Roeder, the embassy’s Air Force attaché. The reading material supplied by the captors was limited to the boating classifieds of the Washington Post, and it happened that Roeder knew boats. So Rosen and Roeder would pick out boats from the listings and then lie back and close their eyes, and Roeder would narrate a boat trip on the Chesapeake Bay. They did that every night.

One day, without notice, the hostages were led outside, packed into a truck, and transferred to the notorious Evin Prison in Tehran. The site of torture and executions of dissidents, the prison was an improvement in that it was warmer and the hostages were four to a cell, so Rosen had people to talk to. For exercise, he and the others would walk in a line around the tiny cell for miles and miles.

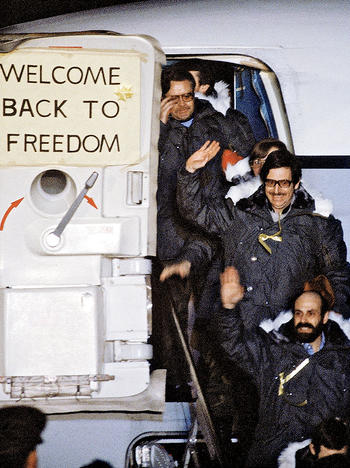

On January 20, 1981, president-elect Ronald Reagan was inaugurated in Washington. In Tehran, the hostages were told to pack their things. Cut off from the outside world, Rosen and the others had no idea that the United States, with Algeria as the intermediary, had agreed to unfreeze $8 billion in Iranian assets as part of a deal to release the hostages. They had spent 444 days in captivity.

“The students blindfolded us, marched us out, put us on buses,” says Rosen. “We didn’t know where we were. We’re screaming at them, they’re screaming at us. The bus stopped, and as we got out they tore off our blindfolds, and there was a gauntlet of students, and they spat at us. We were at the airport. I saw a light pointing toward us — an Algerian Airlines plane. We got onboard and waited.” The plane did not move until after Reagan was sworn in. Over Turkish airspace someone uncorked champagne, but Rosen was too dazed to celebrate. “I was jubilant in one way and fearful in another. I thought: Am I ready for this? Am I really ready for freedom? Am I really ready to see Barbara and the kids? Am I sane enough?”

After the homecoming — after the reunion with Barbara and with Ariana, now two, and with Alexander, now four; after meetings with Carter and Reagan; after the standing ovation in St. Patrick’s Cathedral, the prayers at Temple Emanu-El on Fifth Avenue, and the ticker-tape parade in Lower Manhattan — Rosen had to readjust. He was home, but at the same time he was far, far away.

“I came back to a situation where my family was different in certain ways,” Rosen says. “My integration back into the family was slow. I wanted to be very gentle with the kids, especially with Ariana, who was just a baby when I left. I wanted to make sure that she wasn’t seeing me as a stranger.”

Major League Baseball played an unexpected role. It was the only organization that reached out to the former hostages, offering them free tickets to games. Though the kids were very young, Rosen would take them to Shea Stadium. “Barbara would urge them to go out with me, because in the very beginning they wouldn’t go out with me at all,” Rosen says. “The ball games played a very important role in strengthening our relationship.”

There is a slight catch in his voice when he talks about this. “It was so good to be with the kids. They made it easier on me. They were there for me in so many ways, even though they were just little ones. It was great to just spend time with them and to be more of the father that I wasn’t during that period.”

Shortly after Rosen returned, Columbia president Michael Sovern ’53CC, ’55LAW, ’80HON offered him a fellowship to do research on Iranian novelists and Central Asian history. Rosen accepted, and the family moved to Riverside Drive. “It was a daunting period, because I was undergoing treatment for depression,” says Rosen. After the fellowship, “there was the question of going back into the Foreign Service. I had a great opportunity to go to Italy or India, but Barbara could not agree to this for fear of something happening again.”

Instead, Rosen became assistant to the president of Brooklyn College, where he organized the first academic conference on post-revolution Iran. He gave press interviews, and he and Barbara wrote a book, The Destined Hour, about how the hostage crisis affected the family. “Working on the book helped me process what had happened,” he says. In 1995, he was named executive director of external affairs at Teachers College, where he became a beloved staff member. Still, he suffered recurring bouts of PTSD — what he describes as “an overwhelming sense of a loss of self.”

Yet for all the trauma, Rosen never lost his perspective. “When it was over, I could at least say that as bitter as I was toward those who held me, I kept a sense of ‘There’s Iran, and there’s the revolution.’ I still feel that way. I was a victim of the revolution, but that doesn’t change my basic attitude about Iran and Iranians. Many are suffering under this regime, and I feel bad for them as much as I felt bad for myself during that hostage crisis. I’m not going to destroy my own worldview. I don’t want to live in hate.”

Rosen has backed up that philosophy with action. In 1998, he accepted an invitation to a conference in Paris to appear with Abbas Abdi, the mastermind of the embassy takeover, in a symbolic gesture of conciliation. Knowing that Abdi had had run-ins with the Iranian regime, Rosen figured that their meeting might show hard-liners on both sides that there was room in the middle to build trust. So he, Barbara, and Ariana went to Paris. Rosen remembers entering the hotel lobby days before the conference and he and Abdi spotting each other. “He called me over, and we sat and started talking as if nothing had happened,” Rosen says. “It was wild. We discussed US–Iran relations and our families, then we said goodbye until the meeting a few days later.

“The next morning he knocked at our door and held out a book on Iranian art and architecture and said, ‘This is a gift from me to you and your family.’ And every day, whenever we met, he gave me something from Iran.” Rosen read in Abdi’s gestures more than a twinge of remorse. “He saw my family, saw who we were, saw that I really cared about Iran and wanted it to be a free and open state.”

At the conference, however, they both stiffened their stances, with Rosen condemning the takeover. The state-run Iranian press vilified both Rosen and Abdi. “When we said goodbye, I told him, ‘I hope I haven’t caused you any problems.’ And in fact he did go to jail. The first indictment against him was as a pollster — he had polled Iranians about how they felt about the US, and the results showed that despite everything, many Iranians had a positive feeling. The second indictment was for meeting with me.”

Rosen has always been a teacher. He taught English in Iran for the Peace Corps and afterward taught high-school science in New York. And months after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, he embarked on an educational mission as demanding as anything he’s ever done. The job was in Afghanistan.

In the 1950s, Teachers College began working with the ministry of education in Afghanistan on creating textbooks and curricula for high-school students, a project that ended abruptly with the 1978 Soviet-backed coup. But in 2002, with the Taliban government ousted, UNICEF approached TC president Arthur Levine about reviving the program. Levine asked Rosen to lead it. “I didn’t want to give up my position, which I loved, but this was an amazing opportunity,” Rosen says.

Rosen and Margaret Jo Shepherd, a professor emerita of education at TC, were tasked with creating new textbooks from scratch, assisted by TC students and Afghanis. They flew to Kabul and soon found that doing the job in such a chaotic, depleted country was nearly impossible. Aside from safety concerns, Rosen and Shepherd dealt with spotty electricity, poorly educated teachers, inexperienced writers, and quarrels over the role of religion in the books. They worked seven days a week for two and a half years to produce the country’s first illustrated textbooks, written in Dari, Tajik, Pashto, and Uzbek. “It took a lot out of us,” says Rosen. “But no matter what, we forged on.”

That level of commitment is typical of Rosen. “Barry is such a positive person,” says Shepherd. “He’s thoughtful, open, authentic, and gregarious and has a natural feel for diplomacy. When he goes into a country, he becomes a part of it to the extent that he can. He believes in public service not only because he thinks it’s important for people to help each other but also because it can be helpful to the person providing the service.”

Rosen remains engaged with human-rights issues in Iran and is involved with Hostage Aid Worldwide, a nascent organization of survivors of hostage ordeals that uses data, including recently unclassified State Department documents, to better understand the issue of hostage-taking. And he has maintained contact with some former Iran hostages, mostly in their ongoing, frustrating effort to get compensation from the US government. “A group of us are working with lawyers, so we’re always in touch in some way,” he says. “But many people don’t communicate anymore. Some are in their late eighties. It gets harder as time goes on.”

Retired since 2016, Rosen has arrived at a place of security and self-knowledge. His kids have children of their own, and he and Barbara are busy grandparents. Rosen still thinks every day about Iran, and his heart is with the Iranian human-rights activists who are being detained in the same prison that had held him and his fellow hostages. And if he can’t heal Iran–US relations, he has managed, through love and hard work, to heal himself. “It’s been a long process, but it’s also taught me a lot, and I think it’s made me a better person,” he says. There could hardly be a greater journey than that.

This article appears in the Winter 2020-21 print issue of Columbia Magazine with the title "Soul Survivor."