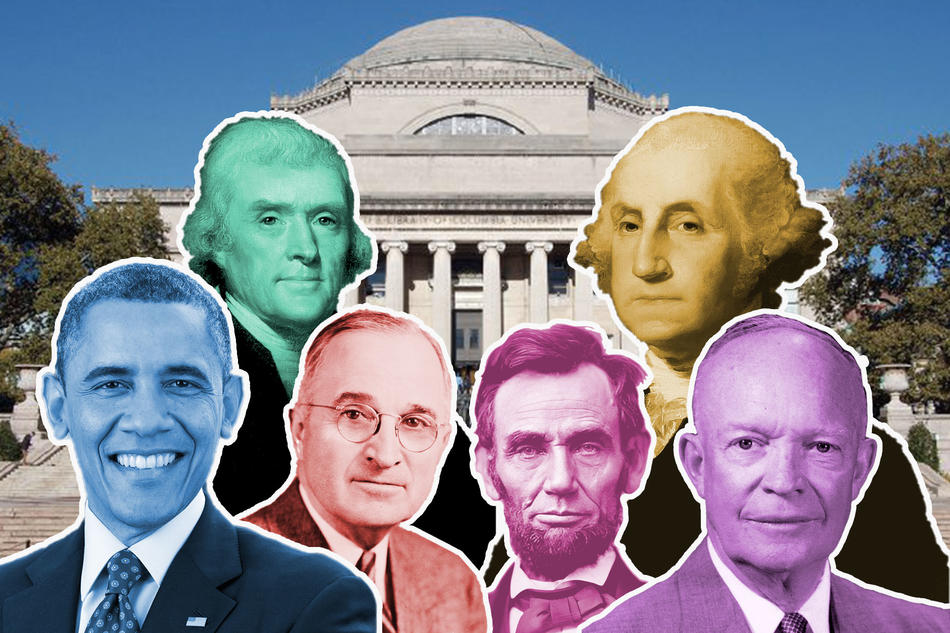

An Incomplete History of Columbia's Connections to the Highest Office in the Land

George Washington’s son slept here

John (Jacky) Parke Custis was four years old when his mother, Martha Dandridge Custis, married George Washington, a twenty-seven-year-old Virginia planter and member of the colony's legislature. Custis was a wild child who loved horses and guns and hated books. But Washington was intent on educating his unruly stepson and paid the boy’s way into King’s College in 1773.

Custis arrived at King’s in May, but the death of his sister that summer and his engagement to Eleanor Calvert, together with his lack of interest in schooling, curtailed his college career after just four months.

Custis married, had four children, and served under his stepfather — now General George Washington — as his aide-de-camp at the Battle of Yorktown in 1781, the last major land battle of the Revolutionary War. During the conflict, Custis contracted “camp fever” (perhaps typhus or dysentery) which killed him at twenty-six. In 1789, Washington became the first president of the new and sovereign nation the United States of America. Though the Father of His Country never had biological children, his grandkids were a joy and comfort in his old age.

Jefferson and Hamilton became campus neighbors

On June 2, 1914, Columbia dignitaries unveiled a statue of Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, in front of what is now called Pulitzer Hall, home of the Journalism school. The statue, by William Ordway Partridge 1885CC, was a gift from J-school founder Joseph Pulitzer to the City of New York. Pulitzer’s executors chose to install the bronze sculpture in front of the new academic building that Pulitzer had funded. The statue was a stone’s throw from Partridge’s 1908 figure of Alexander Hamilton in front of Hamilton Hall, an apposition that seemed to embody the standoff between the commerce-minded Federalists (Hamilton), who wanted a strong central government, and the agrarian-minded Democratic-Republicans (Jefferson), who supported states’ rights.

At the ceremony, University president Nicholas Murray Butler, surrounded by trustees and faculty, said, “How significant it is that after the lapse of a century and more, the lifelike figures of the two great antagonists on the battleground of early American politics stand side by side.”

Columbia regained a long-lost White House letter

In 1983, a woman in Scotland, Jane Haldane, found an old letter in a closet. Dated June 26, 1861, it was addressed to Charles King, president of Columbia College. The writer of the letter thanked King for coming to the White House, where King had conferred upon the writer an honorary degree. The signer of this 122-year-old thank-you note was Abraham Lincoln.

Haldane donated the lost letter to the University, where a facsimile is now on display in the Alumni Center.

Our stalwart president ran for US president — and lost

In the presidential primaries of 1920, Columbia president Nicholas Murray Butler ran as a Republican, believing himself a man of destiny and confident that he would win the nomination. He sounded warnings about the encroachment of Bolshevism and trumpeted patriotic mercantile values. With his robust intellect and connections to the wealthy and powerful, Butler felt he was vastly superior to the others in the Republican field, which included Illinois governor Frank Lowden, the favorite; General Leonard Wood, a Harvard-educated doctor who commanded the Rough Riders during the Spanish-American War; Hiram Johnson, an isolationist California senator who, unlike Butler, had opposed America’s entry into World War I; and Ohio senator Warren G. Harding, notable for his lack of intellect (“the archetype of the Homo boobus,” sneered H. L. Mencken). Butler once referred to Harding as “a cheese paring of a man.”

But when no candidate garnered the requisite 471 votes at the Republican Convention in Chicago, a cabal of senators huddled in the proverbial smoke-filled hotel room and agreed to throw their weight behind Harding. Butler finished at the bottom of the heap — a tremendous blow to his titanic ego. Years later, in Across the Busy Years, his 1939 autobiography, Butler placed himself at the center of the convention’s climax, in a small back room with Harding and Lowden: “In an instant,” Butler wrote, “the door of the room in which we three were sitting burst open and Charles B. Warren of Michigan leapt into the room, shouting: ‘Pennsylvania has voted for you, Harding, and you are nominated!’ Harding rose, and with one hand in Lowden’s and one in mine, he said with choking voice: ‘If the great honor of the Presidency is to come to me, I shall need all the help that you two friends can give me.’”

A faculty member resurrected Grover Cleveland

Columbia history professor Allan Nevins ’60HON wanted to compile a book of the letters of Grover Cleveland, the former New York governor who became the twenty-second president (1885–1889) and twenty-fourth president (1893–1897). In 1932, Nevins put out a call for Cleveland’s letters by composing his own letter — to the editor of the New York Times. “Numerous letters by Mr. Cleveland are known to be in private hands throughout the country,” Nevins wrote. “We earnestly request all persons holding them to send either the originals or careful copies to the editor of the collection, Professor Allan Nevins, Columbia University, New York City.”

Nevins amassed a good deal of material and published a 766-page doorstop titled Grover Cleveland: A Study In Courage. The book won the 1933 Pulitzer Prize for biography. That same year, Houghton Mifflin released Letters of Grover Cleveland 1850–1908, selected and edited by Nevins.

In 1948 Nevins founded the Oral History Research Office at Columbia, which captured history through in-depth interviews. Now called the Columbia Center for Oral History Research, the office conducted the presidential oral history of Dwight D. Eisenhower ’47HON and is currently at work on the Obama Presidency Oral History Project.

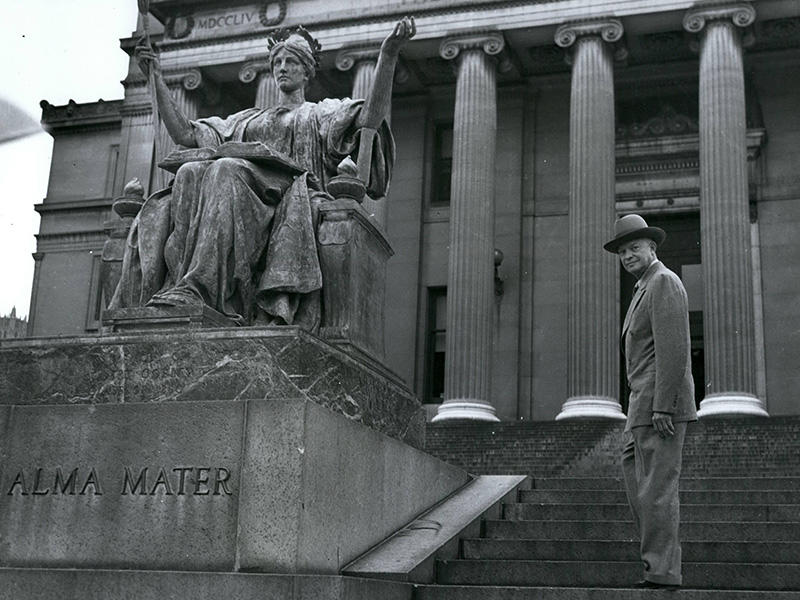

Our absentee president ran for US president — and won

In May of 1948, Dwight D. Eisenhower, the United States Army general who led the Allied invasion of France during World War II, became president of Columbia University. Though he traded his field jacket for an academic gown, Eisenhower never got comfortable in his residence at 60 Morningside Drive. Two years into his term, with the Cold War heating up, Eisenhower was asked to serve as Supreme Commander of NATO forces in Europe, and on December 19, 1950, he took his second leave of absence from Columbia, resettling at NATO headquarters near Paris. His plan was to return immediately to Columbia upon his release from the military. In the meantime, Provost Grayson Kirk would be acting president.

But plans changed. With a national election scheduled for 1952, the US presidency beckoned, and Eisenhower tossed his hat in the ring. His quarters at President’s House remained empty as he hit the campaign trail. In July, he was nominated as the Republican candidate for president. When he won the general election in November 1952, he was still officially president of Columbia. Finally, on January 19, 1953, Eisenhower resigned from the University. The next day, at inauguration ceremonies in Washington, he was sworn in as president of the United States.

Truman gave ’em hell on Morningside

Harry Truman was six years out of office when he visited Columbia in April 1959 to give a three-part lecture. From April 27 to 29, in a crowded McMillin Theater (now Miller Theater), Truman chatted informally about the presidency, the Constitution, and the perils of demagoguery.

A president, he said, is the “absolute commander in chief of the Armed Forces” whose privilege it is “to appoint generals, and sometimes to fire them if necessary.” He is “the maker of the foreign policy of the United States, absolutely responsible for our relations with other countries. No one else can do it.”

Truman called the Constitution “a plan but not a straitjacket,” saying that “the president never goes outside the Constitution, but he may stretch it a little.” As for demagogues, Truman, whose presidency coincided with Senator Joseph McCarthy’s anti-Communist crusade, warned against those “who try to circumvent the Constitution during periods of political hysteria.”

During the Q&A, Truman was asked about his decision to drop atomic bombs on Japanese cities to hasten the end of World War II. “The atom bomb was no ‘great decision,’” the former president said. “It was used in the war, and for your information, there were more people killed by firebombs than dropping of the atomic bombs accounted for. It was merely another powerful weapon in the arsenal of righteousness.”

Columbia docs kept Hoover running

When Herbert Hoover, the thirty-first president, died in his suite on the thirty-first floor of the Waldorf Astoria in 1964, he was ninety years old. Until then, among American presidents, only John Adams had lived as long. And while Adams had the most famous doctor in America, Benjamin Rush, Hoover had the advantage of modern medicine.

Two years before his death, Hoover was admitted to Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital to have a tumor removed from his large intestine. The surgeon was Rudolph Schullinger 1923PS, a professor of clinical surgery, who had successfully removed Hoover’s gall bladder in 1958. Schullinger and his team saw the former president into his ninth decade.

On Hoover’s milestone birthday in 1964, a journalist asked him how it felt to be ninety. “Too old,” came the reply.

The 2008 presidential campaign featured three Columbians, two of whom were not named Obama

2008 was a big year for Columbians and the presidency. The presidential race featured three Columbia graduates: Illinois senator Barack Obama ’83CC; Las Vegas oddsmaker and conspiracy theorist Wayne Allyn Root ’83CC; and former Alaska senator Mike Gravel ’56GS. And in a September ceremony, two former presidents who never finished law school — Theodore Roosevelt 1882LAW and Franklin D. Roosevelt 1907LAW — were awarded posthumous degrees.

Gravel, whose claim to fame was reading the Pentagon Papers into the record on the Senate floor in 1971, had one of those heady, short-lived bursts of attention common to novelty candidates early in the cycle, when his take-no-prisoners debate performances raised hopes among opponents of the Iraq War, before media interest reverted to the top-tier candidates. Root, a brash, self-promoting entrepreneur, ran as a Libertarian, and in May 2008 he was named the vice-presidential candidate on the Libertarian ticket, headed by former Georgia congressman Bob Barr. Obama, a one-term senator, won the Democratic nomination and defeated Arizona senator John McCain in the general election to become the first Black president of the United States.

Obama would serve two terms. Root would return to Las Vegas to promote myths about Obama’s birth certificate on his radio show. Gravel faded from the public view, but in April 2019, a month before his ninetieth birthday, a pair of eighteen-year-olds in New York decided to revive his candidacy. The teenagers became Gravel’s campaign managers, and Gravel agreed to run, if only to inject his anti-imperialist spleen into the conversation. He did not, however, poll high enough to qualify for the Democratic debates, and he ended his campaign that August, endorsing youngsters Bernie Sanders and Tulsi Gabbard.