"Use the busts. Tell that story. Go."

These were the marching orders that Valerie Paley ’11GSAS was given in 2008 when the head of the New-York Historical Society Museum & Library asked her to curate an exhibition called New York Rising. The show, which combines a crowded, salon-style display of artifacts and images with touchscreen technology, was designed to be the centerpiece of the society’s first-ever permanent installation and a key part of its recent $70 million renovation.

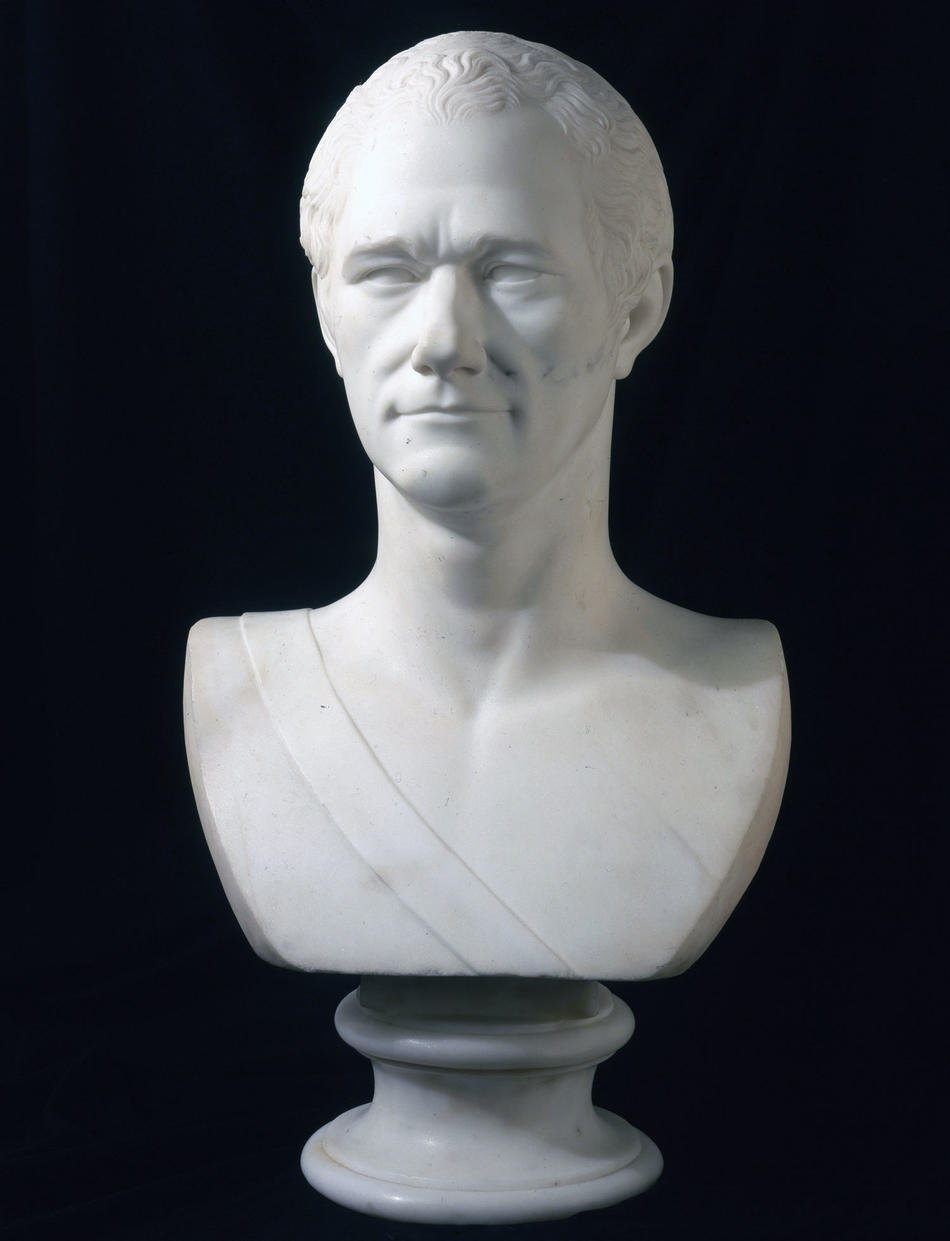

Paley, who is the society’s historian for special projects, faced a daunting curatorial task. The show’s intended focus was Revolutionary and Federalist New York, including the city’s occupation by the British, its largely unheralded role as America’s first capital, the birth of Wall Street, and the 1804 founding of the New-York Historical Society itself. Paley knew she had to employ the traditional artifacts in the collection, starting with the busts. This posed a serious problem.

“We don’t do the history of dead white men,” Paley explains. “It’s not the sort of history we’re taught in the academy anymore, nor is it the sort of history that is revered among scholars. We want to do something a little deeper and more nuanced. But to superimpose the new social history on busts of dead white men can be a fraught process.”

Paley was born in New York City in 1961 and grew up in Greenwich Village, where, she says, “I always had this palpable sense of history around me.” But her route to becoming a historian was circuitous: she trained, from age three to fourteen, with the Joffrey Ballet, until an injury caused her to switch to modern dance (as a teenager she performed with the Valerie Bettis Dance/Theater Company). Following what she calls her “thwarted career as a ballet dancer,” Paley entered

Vassar College, where she majored in English and psychology. After graduation, she joined her father’s graphic-design business, becoming first art director, then creative director. She retired in 1990 when her son was born (she now has a daughter as well and is married to a “semi-retired money manager”). But she soon found that “stay-at-home mothering as a full-time job wasn’t really my thing.”

So, at thirty-three, Paley entered Columbia as a master’s student in liberal studies, with a concentration in American studies. “Everything I did there was tailored around the idea of New York history and New York culture and architecture and preservation,” she says. “I absolutely loved it. I was almost bereft when I finished.”

Encouraged by her mentor, Kenneth T. Jackson, the Jacques Barzun Professor in History and the Social Sciences, Paley laid aside plans to be an archivist and enrolled in Columbia’s doctoral program in history. She received her PhD this past May and was class valedictorian. Her dissertation discussed how the trustees of New York cultural institutions “shaped the cultural infrastructure of the city” and argued that the city’s “openness to difference . . . made for some exceptional, world-class institutions.”

Meanwhile, Paley had been volunteering at both the New-York Historical Society and the Museum of the City of New York. In 2002, Jackson, who was president of the New-York Historical Society at the time and is now a trustee, offered Paley a position as editor of the society’s journal. Paley accepted. This led her to the editorship of several exhibition catalogs. Then, in 2008, she got the call from Jackson’s successor, Louise Mirrer: would Paley be interested in creating the new permanent installation in the Robert H. and Clarice Smith New York Gallery of American History?

“She’s very good and very smart,” Mirrer says, when asked why she selected Paley. “She had just completed a dissertation on this period, so the research was very fresh in her mind. And I knew I could work with her. People are going to judge the institution on this installation, and I wanted personally to make sure it met all expectations for giving people a palpable sense of history.”

And her exhortation to “use the busts”?

“Busts, in my opinion, are one of the most visceral expressions of the founding era,” Mirrer says. “You’re here with these people, they look at you, and I thought that museum-goers would feel the thrill of historical discovery were these people to come alive for them.”

So Paley asked her staff to survey the relevant busts in the collection. Then, she says, “all of a sudden, we started making this Venn diagram of relationships. For example, John Jay [1764KC] and Robert Livingston [1765KC]: frenemies. They were very close friends who met in college and then became bitter enemies and political rivals.” In the collection were busts of both statesmen, as well as letters between them that hinted at the complexity of the relationship.

In examining the era, Paley’s staff eventually produced an astonishing three thousand pages of research, which they boiled down to five hundred. They called on Small Design Firm, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to help them create technology that would allow visitors to drill deep into both the history and the objects on view — “almost the way a historian does research,” Paley says. Eventually, the touchscreens were supplemented by wall labels, an iPhone app, and a program guide.

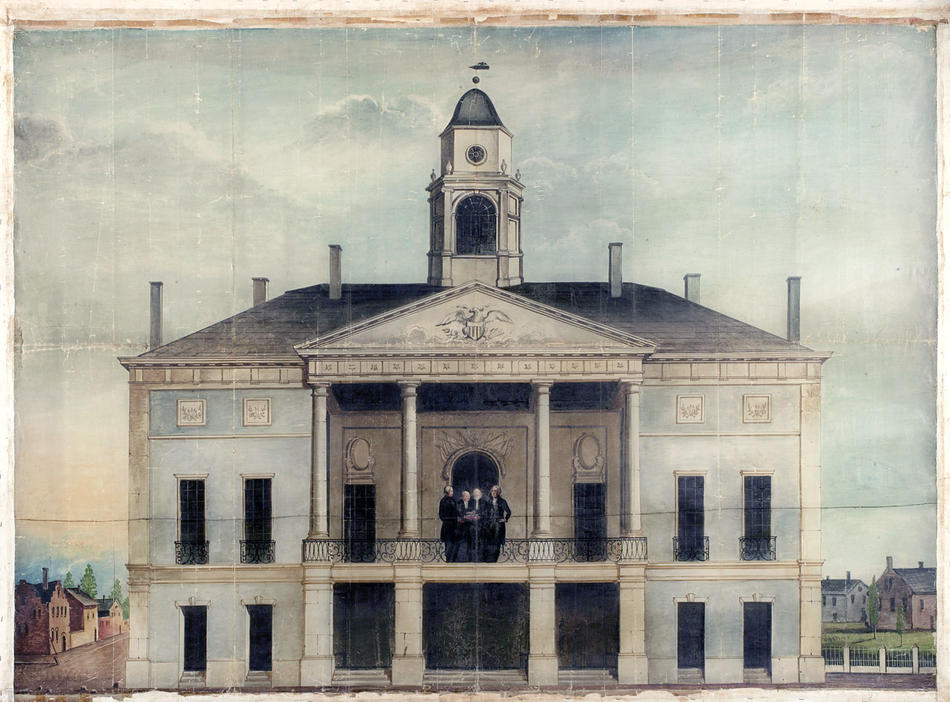

New York Rising has five sections: “Revolution,” “Marketplace,” “Capital,” “Politics,” and “Civilization.” Each is anchored by a large painting that serves “as a kind of gateway into the larger story that we’re trying to tell,” Paley says. Vitrines contain an apparent jumble of smaller objects, including a brick from a tavern, a pair of child-sized slave manacles attached to a cast of a child’s hands, and one prize loan, from JPMorgan Chase: the dueling pistols used by Alexander Hamilton 1776KC and Aaron Burr. Below these, at floor level, are objects such as the prosthetic leg of Gouverneur Morris 1768KC and a keg that New York governor DeWitt Clinton 1786CC used to inaugurate the Erie Canal.

And the busts? Instead of positioning them high up, as though “they were looking down at the civilization below,” Paley says, she decided that “we’ll scatter them around the way the men were scattered around the city at the time.”

The exhibition’s juxtapositions are meant to be provocative. Near a large, headless statue of the British parliamentarian William Pitt, targeted by loyalists for his colonial sympathies, hangs a painting of an angry New York mob pulling down a monument to King George III. Beside it is another memento of that scene: a sculptural fragment from the tail of the horse the king was riding. Three artifacts, two acts of vandalism during the American Revolution: the connections aren’t immediately obvious, but, once explained, they convey the tumult of the period.

The display also includes the utterly unexpected — such as a nineteenth-century portrait of a homely woman once thought, incorrectly, to be New York’s royal governor Lord Cornbury (1661–1723), in women’s clothes. An old label on the portrait advances this claim. Paley says she had to battle a curator who didn’t want this historical mistake displayed. “That’s why I want it there — because it’s wrong,” Paley says. “History is a reflection of the time in which it’s written. We use the portrait to represent [American feelings about] the decadence of British culture. But we’re also using it as an object lesson in how history is told.”

In the end, New York Rising suggests that the Revolution and its aftermath didn’t just consist of “men marching around in costumes,” Paley says. “Children were there; slaves were there. We want to capture the hustle, the bustle, the smells, the feeling of what it’s like to live in this period.”

New York Rising, it turned out, was just the starting point of the Smith Gallery, a modern, light-filled expanse visible through glass doors from Central Park. When it became clear that the space could hold more content, Paley filled it with a remarkable variety of exhibits, introducing the society’s collections, aims, and stance toward historical interpretation.

The first exhibit a visitor is likely to encounter is an installation by Fred Wilson titled Liberty/Liberté. Made for a 2006 show, Legacies: Contemporary Artists Reflect on Slavery, the piece incorporates busts of George Washington and Napoleon, a wrought-iron balustrade from Federal Hall (where Washington was inaugurated), a tobacco-shop sculpture of an African-American, and slave shackles. Paley says it suggests a dialogue about “what is liberty to this slave and what is liberty to these freedom fighters who were slaveholders.” The Wilson piece is not only a commentary on the contradictions embedded in America’s founding myths but also serves as an introduction to the historical society itself, showing, Paley says, “that we embrace that sort of critical history.”

One of the most engaging aspects of the Smith Gallery is History Under Your Feet, a tribute to urban archaeology. Displayed below the floor, in nine manhole-like exhibition cases, are such artifacts as the shoes of a child killed in a 1904 fire aboard a steamboat called the General Slocum (the deadliest catastrophe in New York before 9/11) and a crushed clock, stopped at 9:04 a.m., recovered from the World Trade Center debris.

The clock is positioned underneath the scratched and battered door of a fire truck used by first responders on 9/11. Both are adjacent to Here Is New York, seventy-five photographs of the terrorist attacks and their aftermath, including images of the smoke enveloping the World Trade Center, the search for survivors, and a rally in defense of Muslims. Here Is New York faces New York Rising, and, as Paley points out, echoes it both visually, in its salon-style display, and intellectually, as a testament to New York’s capacity to remake itself after disaster.

Also in the Smith Gallery are screens showing collection highlights, a ten-foot-tall display case for large-scale treasures, and a video animation based on Johannes A. S. Oertel’s Pulling Down the Statue of King George III, New York City (1852–1853), which is displayed in New York Rising. The animation, inspired by the painting, responds to the movements of onlookers. When enough people congregate in front of it, the video mob pulls down the statue — a way, Paley says, of reminding visitors that they, too, have a role in the history of New York, that it wasn’t only the men whose heads were cast in marble and bronze who made things happen.

“There’s a process, and there’s a layering of history, and there’s no right and wrong necessarily,” Paley says. “History is part of a continuum — and the museum visitor is part of that.”