The Whitney Museum’s elevator doors open onto a film projected on a black wall. Grainy figures march in what looks like a Vietnam War protest. But the 8 mm footage isn’t as old as it looks. In fact, it was shot by artist Josephine Meckseper in 2004 at a demonstration against the Iraq War. This tangible reminder of art’s continued role in responding to conflict introduces visitors to An Incomplete History of Protest: Selections from the Whitney’s Collection, 1940–2017, an exhibition co-curated by Rujeko Hockley ’05CC that will run until spring 2018.

Throughout the show, a variety of media — film, photography, poster, painting, drawing, sculpture, installation, and text — capture a wide range of protest movements and perspectives. Such breadth in one exhibit reflects Hockley’s philosophy as a curator. “I’m interested in expanding the types of work we see in institutions,” she explains. “At the Whitney that means thinking in the most expansive way possible about what it means to be an American artist.”

Hockley arrived at the Whitney as an assistant curator in March 2017 and brought with her a complex sense of American identity. Born in Zimbabwe to a Zimbabwean mother and an English father, she moved to the United States at age two and grew up in Washington, DC, and New York City. "I'm kind of a hodgepodge of things,” she says.

Hockley’s career took root at Columbia, where, as an art-history major, she studied the ways in which American art has historically represented a relatively narrow spectrum of American people. After graduation, she landed a job as a curatorial assistant at the Studio Museum in Harlem and worked there for two years before moving to Laos to teach English, and then to California to start a PhD program at UC San Diego. In 2012, she joined the staff of the Brooklyn Museum, where she co-organized powerful exhibitions including this year’s We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85, which, Hockley says, “really homed in on the relationship between Black women artists and second-wave feminism.”

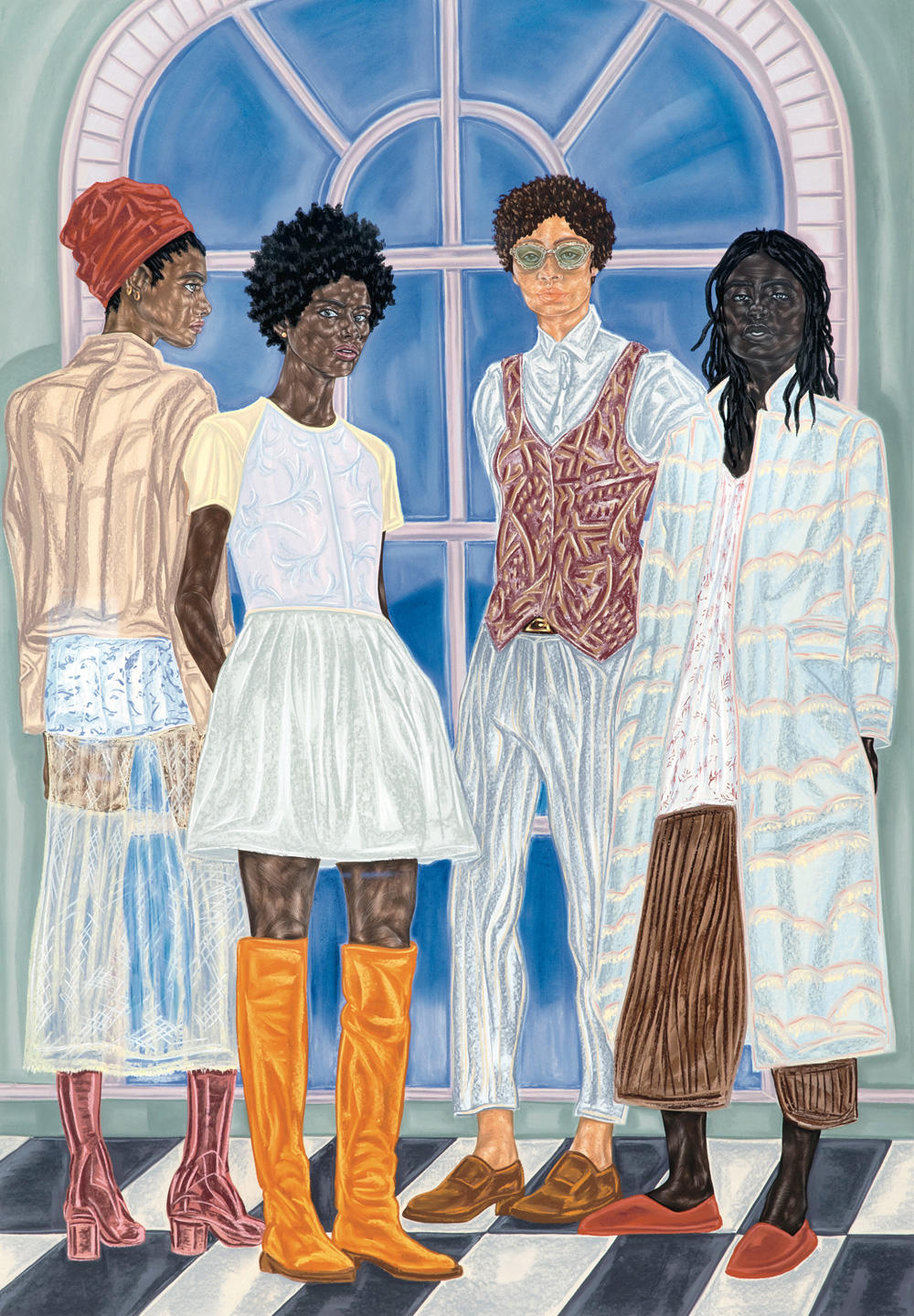

Her latest project at the Whitney, titled Toyin Ojih Odutola: To Wander Determined, features drawings by a Nigerian-American artist who explores themes of identity and narrative through richly textured portraits of fictional characters. Like Hockley, Ojih Odutola is in her early thirties, and, like Hockley, she was born in Africa but grew up in the United States. “Ojih Odutola's also interested in exploring who’s an American and what we talk about when we talk about American art,” Hockley says.

Ojih Odutola's drawings, on view until February 25, aren’t just beautiful; they invite viewers to think about representations of race, class, and nationality. Hockley explains: “Society has a tendency to flatten the experiences of people of color into a kind of monolith — into a singular ‘Black experience,’ for example — and Ojih Odutola pushes audiences to think about the specificities and nuances of individual lives.”

As a curator, Hockley says she is motivated to showcase work that reflects an ever-complex, ever-diverse America. “We’re doing ourselves a disservice if we don’t embrace the full range of human experience,” she says. “Of course, that’s a hard thing to do, and we struggle with it as a nation. But I see great art all the time, and I see people who are really engaged with their current moment and surroundings. And to me, that’s all good.”