As a child, Stefan Sharff liked to scare his mother. Once, while she was on the balcony of their house in Lublin, Poland, Sharff locked the windows from the inside. Moments later he appeared on the rooftop across the street. His poor mother had no choice but to watch in fear as her son stepped onto the ledge of the roof and tottered along it, looking as if he might fall.

Sharff’s life was full of such potent cinematic suggestions. A working filmmaker who shot and edited more than a hundred films, many of them public-television documentaries, Sharff taught film analysis in the School of the Arts at Columbia for thirty years. He helped found the film division of the newly-established School of the Arts in 1965, was chair of the department from 1970 to 1978, and started the PhD program in film studies in 1974. Students remember him as a polite, sharp-witted, and intellectually demanding teacher who spoke with a Polish accent and whose courses were always filled.

“Sharff was probably the best film professor around,” says Raymond Foery ’71SOA, ’97GSAS, a Sharff student and author of Frenzy: The Last Masterpiece, a study of Hitchcock’s 1972 thriller. “When he analyzed a film, it was like nothing any of us had ever experienced.” Oscar-winning director Kathryn Bigelow ’81SOA (The Hurt Locker, Zero Dark Thirty, A House of Dynamite), has described her experience in the film department under Sharff as “peerless” and “extraordinary,” and director James Mangold ’99SOA (Walk the Line, Ford v Ferrari, A Complete Unknown) credits Sharff for imparting to him the beauty of the transitional shot, which takes the viewer from one scene to the next — demonstrating that, as Mangold has said, “the magic of cinema is in the cut.”

For Sharff, narrative film was a kind of language, and he developed a method of breaking down a film shot by shot into its syntactical parts. To demonstrate this in the classroom, Sharff screened movies by Rossellini, Fellini, Bergman, Kurosawa, Truffaut, Godard, and, above all, Hitchcock.

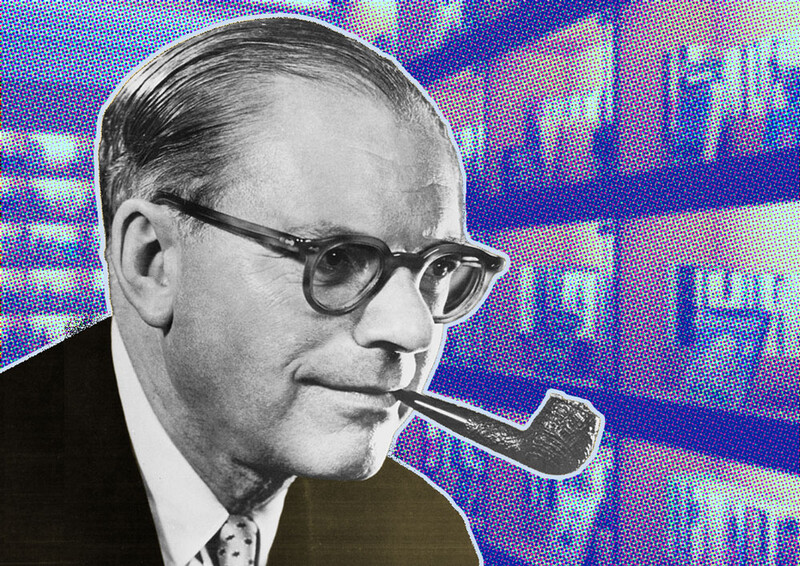

Though Hitchcock was revered by French New Wave directors like Truffaut, Godard, and Chabrol, his artistic reputation in the US suffered from his mass appeal. Film critic Andrew Sarris ’51CC, ’98GSAS, who taught in the film program with Sharff, was one of the first American critics to place Hitchcock in the pantheon of great directors. In his first Village Voice review, for Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), Sarris wrote: “A close inspection of Psycho indicates not only that the French have been right all along, but that Hitchcock is the most daring avant-garde filmmaker in America today.”

For years Sharff had lobbied Columbia to ratify the critical consensus within the film department by honoring Hitchcock with a degree. “Hitchcock was God to my father,” says Sharff’s daughter Monica Sharf ’79BC, ’83SOA, a documentary filmmaker (she spells her last name with one “f”). “And he wanted the honorary degree for Hitchcock because he thought that Hitchcock should be recognized for his contributions to the art of filmmaking.”

In 1972, President William McGill assented. The timing was perfect: Commencement was scheduled for June 6, and Hitchcock’s latest movie, Frenzy, which concerned a serial strangler in London, was to be released that month in New York. This would allow Hitchcock to kill a few birds with one stone: he could get his Columbia degree, give a talk to graduates, and promote Frenzy.

For Hitchcock, the Doctor of Humane Letters would lend academic weight to a shelf conspicuously bare of any Best Director statuettes. And for Sharff, who understood Hitchcock’s cinematic idiom better than anyone, and who insisted on his greatness, the degree would represent a professional and cultural coup, and add another twist to his own unlikely story.

In March of 1939, Hitchcock, forty years old, known for his English thrillers like The Man Who Knew Too Much, The 39 Steps, and The Lady Vanishes, left his London home and sailed to America with his wife and daughter, to begin a new chapter in Hollywood. Within days of arriving in New York, he gave a talk at Radio City Music Hall moderated by John E. Abbott, head of the film library at the Museum of Modern Art. Abbott and his wife, the film critic and curator Iris Barry, taught a course on film history at Columbia University Extension (precursor to the School of General Studies), and Columbia and MoMA cosponsored the Hitchcock event.

“I think that pace in a film is made entirely by keeping the mind of the spectator occupied,” Hitchcock told the audience. “That is why suspense is such a valuable thing, because it keeps the mind of the audience going . . . We used to feel that suspense was saving someone from the scaffold, but there is also the suspense of whether the man will get the girl. I really feel that suspense has to do largely with the audience’s own desires or wishes.”

Later that year, on September 1, Germany invaded Poland, marking the start of World War II. Stefan Sharff, now a young man of twenty, left his hometown of Lublin and crossed into the Soviet Union, leaving behind his family. He enrolled in the Moscow Film School, but when the German army entered Russia in June of 1941, the film industry relocated two thousand miles away, to Alma-Ata, Kazakhstan. Sharff followed, and it was there in Central Asia that he got a dream job: assisting the great Russian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein on Ivan the Terrible Part II.

Eisenstein was famous for his 1925 masterpieces Strike and Battleship Potemkin, and for developing the technique and theory of montage, in which he posited that the “collision” of contrasting images produced meaning beyond the individual shots. In the 1930s, Soviet Premier Josef Stalin commissioned Eisenstein to direct a film about Ivan IV Vasilyevich, the 16th century Grand Prince of Russia. Eisenstein’s task was to portray Ivan’s brutal rule as heroic and unifying — an unsubtle analogue to Stalin. The film was a triumph for both director and dictator.

But Part II was another affair. Under Eisenstein’s wing, Sharff learned the language of film, and also a lesson in defiance: Part II showed Ivan’s descent into madness and cruelty. Stalin was not amused, and the film was suppressed until after his death.

In Lublin, meanwhile, Nazi soldiers forced the city’s forty-five-thousand Jews — one-third of the population — to leave their homes and relocate in the Lublin ghetto. Sharff’s father was shot outside his leather shop. The ghetto was liquidated in 1942. The Nazis sent most of the residents, including what was left of Sharff’s family, to an extermination camp.

Several worlds away, in Hollywood, Hitchcock was flourishing. Though he struggled for creative control with David O. Selznick, the movie producer and executive (and one-time Columbia student) who signed him to a seven-year contract, it was hard to argue with the results: Hitchcock’s first US film, Rebecca, won the 1941 Academy Award for best picture. His output through the war years included the now-classics Suspicion (1941), Shadow of a Doubt (1943), and Lifeboat (1944).

In 1945, as the war ended, Hitchcock prepared to film his espionage thriller Notorious, while Sharff, in smoldering Europe, was merely trying to survive. Fortunately, Sharff had maintained connections in Poland. When the war ended and the Soviets recruited Sharff’s former professor to be a delegate for a coalition Polish government, Sharff became his attaché.

One night, as the story goes, Stalin hosted a state dinner for the delegates in the Kremlin. Sharff attended with the professor. Mid-meal, the professor, an elderly man, began fidgeting. Stalin noticed this, and, flashing the charm that had helped him disarm his rivals and amass power, offered to escort the professor — and Sharff — to his private lavatory. It’s tempting to imagine a Hitchcockian crane shot, the camera swooping behind the trio as they proceed through the grand, gilded hall, through a heavy door, and into a regal chamber furnished with Russia’s finest plumbing fixtures. “I remember experiencing a Beckett-absurdist sensation,” Sharff wrote in a 1984 article in Encounter, “standing there urinating next to Stalin.”

After the war, Sharff helped liberate a prison camp in Poland. But he clashed with the communist leaders, and in the late 1940s, he emigrated to the US, where he became chief of the newsreel division at the United Nations.

He also began making his films. One of them, Memento, a seven-minute public-service announcement about automobile safety funded by AT&T, bears the DNA of Eisenstein and Hitchcock: shot in a vast junkyard of mangled cars, Sharff employed slow pans, rapid-fire montages, lingering shots of steel wreckage heaped like the ruins of an extinct civilization, impressionistic recreations of crashes, and — as a speeding motorist argues with his wife in voice-over — gut-tightening suspense. For another film, Selma-Montgomery March –1965, Sharff took four of his Columbia students and five Bolex cameras to Alabama to cover the fifty-four-mile march led by Martin Luther King, Jr. Each student shot a specific element: the marchers’ feet, their faces, the spectators, and the sky, where a loud helicopter hovered. The result was a twenty-minute visual poem set to Black spirituals, with the music intermittently drowned out by the grinding whump-whump-whump of the chopper’s blades.

When Sharff wasn’t shooting and cutting film, he was watching it and studying it. And in the 1950s and early 1960s, the wisest eyes were on Hitchcock, who in that period reeled off Strangers on a Train (1951, based on the novel by Patricia Highsmith ’42BC), Rear Window (1954, based on the novel by Columbia dropout Cornell Woolrich), Vertigo (1958), North by Northwest (1959), Psycho (1960, starring former Columbia undergrad Anthony Perkins), and The Birds (1963).

Sharff arrived at Columbia in 1963 and immediately made an impact. “Stefan had a way of looking at films that was truly unique,” says Foery. “He almost never bothered with the acting or the performances. He was always concerned with where the camera was and what it was doing, and how this shot meshed with the previous shot and predicted the next shot.”

For his class, Sharff would focus on about forty minutes of a given film. “He would break it down shot by shot, revealing the cinematic language that was in play,” says another former student, Larry Burke ’71SOA, who taught film for fifteen years at Simon’s Rock at Bard College. “His insights were just eye-opening.”

In early 1972, Burke and Sharff took a trip to Hollywood to try to find a distributor for Sharff’s second and last feature film, Run. Sharff always tried to involve his students with his work. For Run, Burke was the camera operator and Foery was the production manager. While in Hollywood, Burke recalls, Sharff arranged a meeting with Hitchcock, to iron out details of Hitchcock’s forthcoming Columbia visit.

Sharff and Burke went to Hitchcock’s office at Universal Studios. Burke can still picture Hitchcock, sitting behind a large, imposing desk, with the Universal lot out the window. “I was twenty-four and in the presence of the master, and I was completely tongue-tied,” Burke says. During the hourlong visit, Sharff queried Hitchcock about his next film project, called Family Plot, which would be Hitchcock’s last. “Stefan asked, ‘What is it about this particular story?’” Burke says. “The story concerned two couples who had absolutely no reason to be connected to each other, and Hitchcock said he loved the cinematic challenge of how to create this parallel action where eventually the couples would come together. For him, that moment of their crossing paths was the most interesting thing about it.”

Now, in real life, two other paths, Sharff’s and Hitchcock’s, had improbably crossed. And, as in the best dramas, their meeting — so impossible to imagine in 1939 — had, in 1972, a certain cinematic inevitability.

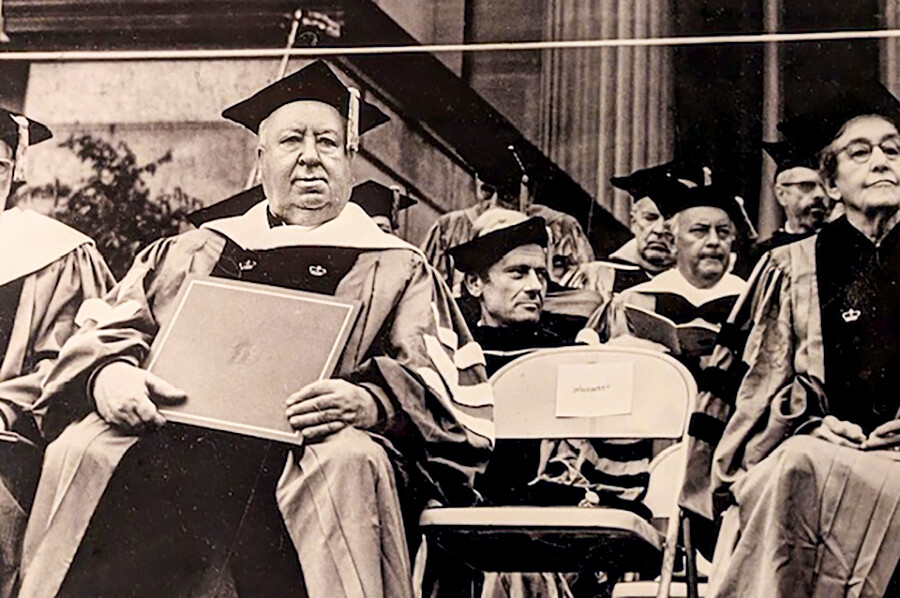

“For forty-seven years you have fashioned rousing entertainments for mass audiences without submerging your creative identity in the collective process of movie-making,” intoned Columbia president William McGill on that sunny June day as Hitchcock, in a capacious gown, sat among 6800 graduates and undergraduates on Low Plaza. “From The Pleasure Garden in 1925 to Frenzy in 1972, you have displayed an understanding of both the concrete and connotative power of the photographed image in the development of a visual language.”

As Hitchcock rose to accept the degree, the graduates, whom Sharff had supposed would see Hitchcock as a relic of a past generation, stood and applauded. That moved Sharff greatly. After the ceremony, Hitchcock spoke at a luncheon in Ferris Booth Hall, where he told an amusing story about the filming of North by Northwest. Then he continued his New York promotional tour for Frenzy.

Sharff taught for twenty more years. He was married three times and had six children and two stepchildren. After retiring in 1993 he moved to New Hampshire, where he finished his third book of film analysis, The Art of Looking in Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1997), which followed Hitchcock’s High Vernacular (1991) and Elements of Cinema (1982). Sharff died in 2003 at age eighty-three.

In Hitchcock’s High Vernacular, Sharff credits Hitchcock, who died in 1980, with propagating the most elevated style of the visual dialect that Sharff had spent his career defining: “I believe him to be one of the great masters, a man who persistently experimented with new forms, who always sought new ways,” Sharff writes. “While an artist of considerable purity, he was not an extremist and was able to attain enormous popular appeal. This fact alone may be the beginning of proof that elegant cinema ‘language’ can reach and gratify a mass audience.”