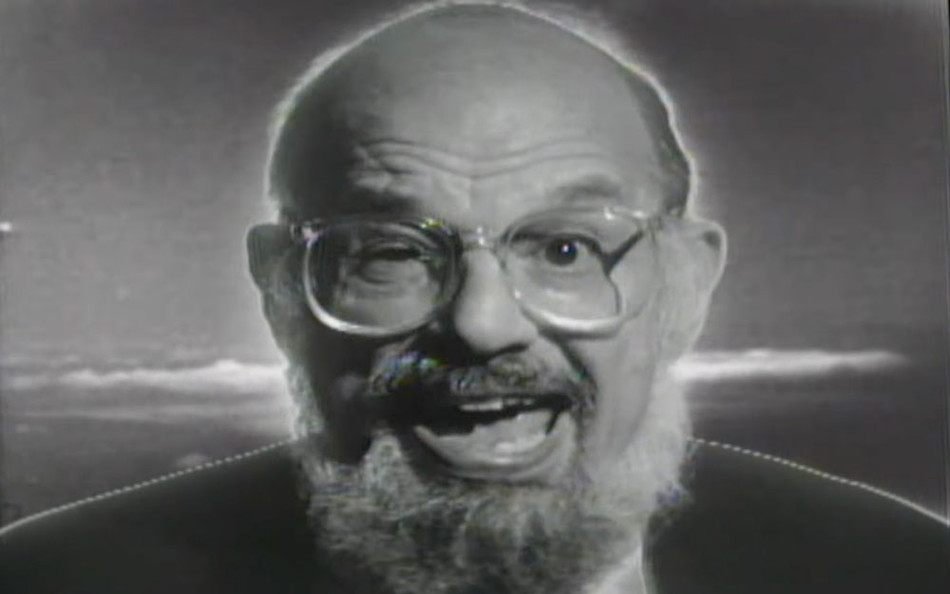

Allen Ginsberg makes no bones about his love of skeletons

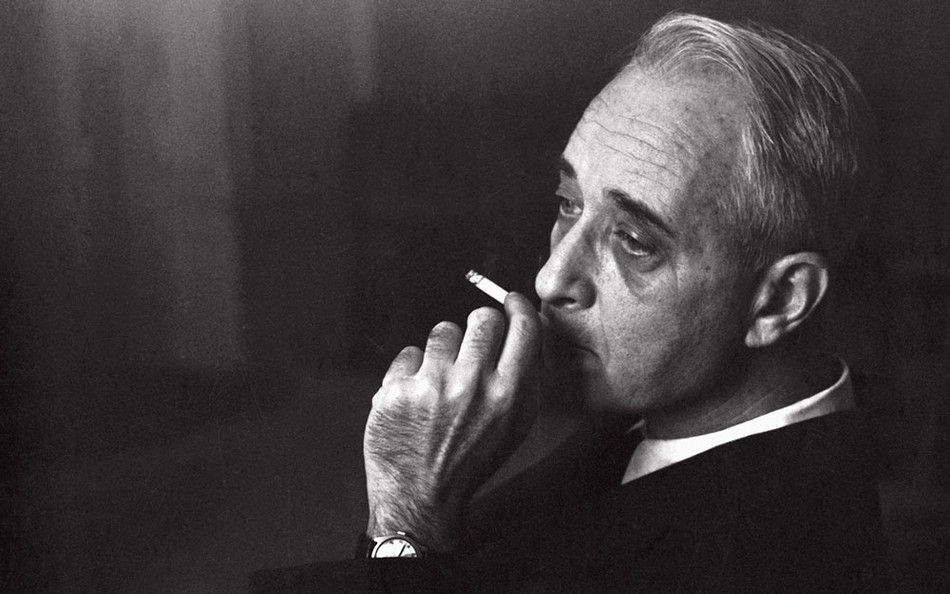

“Genius Death, your art is done / Lover Death, your body’s gone / Father Death, I’m coming home,” writes Allen Ginsberg ’48CC in “Father Death Blues.” Like poets from Poe to Plath, Ginsberg has a macabre sensibility that goes well with Halloween. There’s a story, unconfirmed, that on one Halloween in the late 1970s, Ginsberg and Bob Dylan, wearing masks, took Dylan’s kids trick-or-treating in the LA neighborhood of Pacific Palisades (they managed not to be recognized). More verifiably, the two artists once visited the grave of former Columbia Lions halfback and literary bum Jack Kerouac in Lowell, Massachusetts. There, Ginsberg recited a passage from a Kerouac poem, speaking of "Streets where phantoms / Hastened out of sight ..."

In 1996, the year before his own death, Ginsberg recorded a song called “Ballad of the Skeletons,” with musical help from, among others, Paul McCartney and Philip Glass. In his lyrics, with their litany of archetypes (the Supreme Court Skeleton, the Free Market Skeleton, the Macho Skeleton), Ginsberg leaves no headstone unturned. The video was directed by Gus Van Sant.

“It’s a great collage,” Ginsberg told journalist Steve Silberman. “[Van Sant] went back to old Pathé, Satan skeletons and mixed them up with Rush Limbaugh and Dole and the local politicians, Newt Gingrich, and the president. And mixed those up with the atom bomb. When I talk about the electric chair — ‘Hey, what’s cookin’?’— you got Satan setting off an atom bomb, and I’m trembling with a USA hat on, the Uncle Sam hat on. So it’s quite a production. It’s fun.”

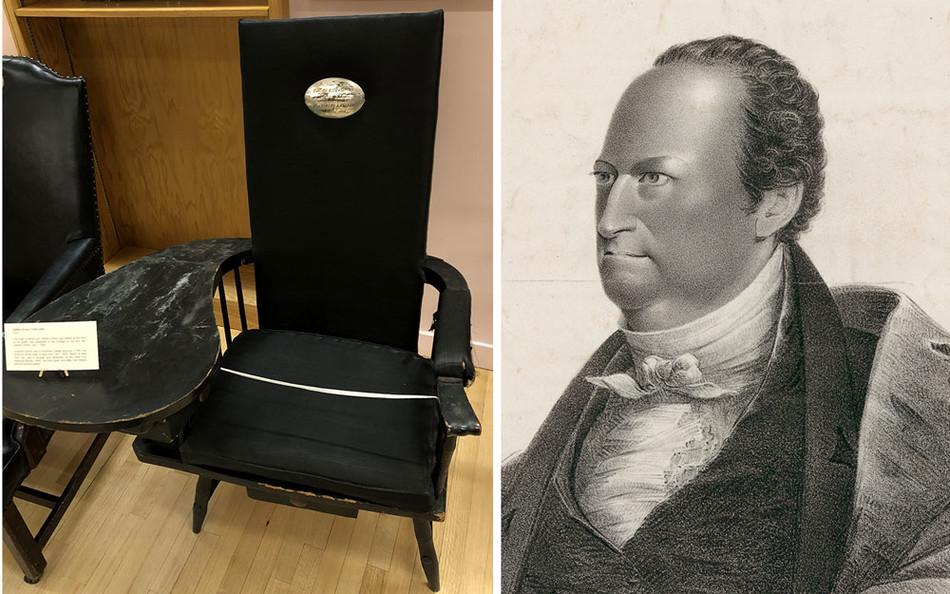

There’s something spooky about DeWitt Clinton

Since his death in 1828, DeWitt Clinton 1786CC, 1826HON, so active in life, seems never to have gone to his rest. Although he was mayor of New York City, governor of New York State, a US Senator, and a presidential candidate in 1812 — not to mention a member of the first graduating class of Columbia College (formerly King’s College) and the visionary behind the Erie Canal — Clinton died broke, and his remains were stored for years in Albany until his family could afford a nice burial spot. In the 1840s, the new Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn needed some star power in the graveyard to attract new customers. Clinton was an ideal candidate. Arrangements were made, and the family sent the bones downriver. After being held in a Green-Wood vault for several years, his remains were reinterred in 1853 beneath a majestic bronze statue.

It was around this time that American Spiritualism — the belief that the dead can communicate with the living — was growing in popularity. Clinton’s ghost, perhaps disturbed by the decades of uncertainty surrounding the disposition of his skeleton, was rumored to haunt City Hall, and the towns and neighborhoods that honored his name were home to notoriously spooky real estate. In Brooklyn’s Clinton Hill, on Clinton Avenue, sits the Lefferts-Laidlaw House, which was the subject of an 1878 New York Times article detailing the unexplained creakings and rattlings in the Greek Revival mansion, disturbances that baffled even the “infallible Police” who had been summoned to investigate. And in Clinton, New Jersey, the Red Mill, a landmarked 1810 structure, is still said to be haunted by the ghosts of workers who died there in gruesome nineteenth-century accidents (one unfortunate soul fell into a third-floor hopper and was suffocated). Today, for a brief period each October, the site becomes the “Haunted Red Mill,” an attraction offering “an intense experience meant to frighten adults.”

But perhaps the most morbid piece of Clintonia resides in Columbia’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library, on the sixth floor of Butler Library. There, in the Corliss Lamont Reading Room, is a black wooden chair — the very chair, as a plaque notes, “in which Gov. De Witt Clinton was seated at the time of his death.”

Fittingly, Corliss Lamont ’32GSAS, a humanist philosopher and Columbia professor who died in 1995, did not discount the idea of the paranormal. In his 1935 book The Illusion of Immortality, Lamont writes, “Considering how freakish and mischievous are many of the communications and physical manifestations that occur at séances, the hypothesis that impish and non-human demons or elfs are the cause is not without merit. The traditional belief of the Church in diabolical possession, still held in many quarters, is possibly more plausible than the theories of the Spiritualists.”

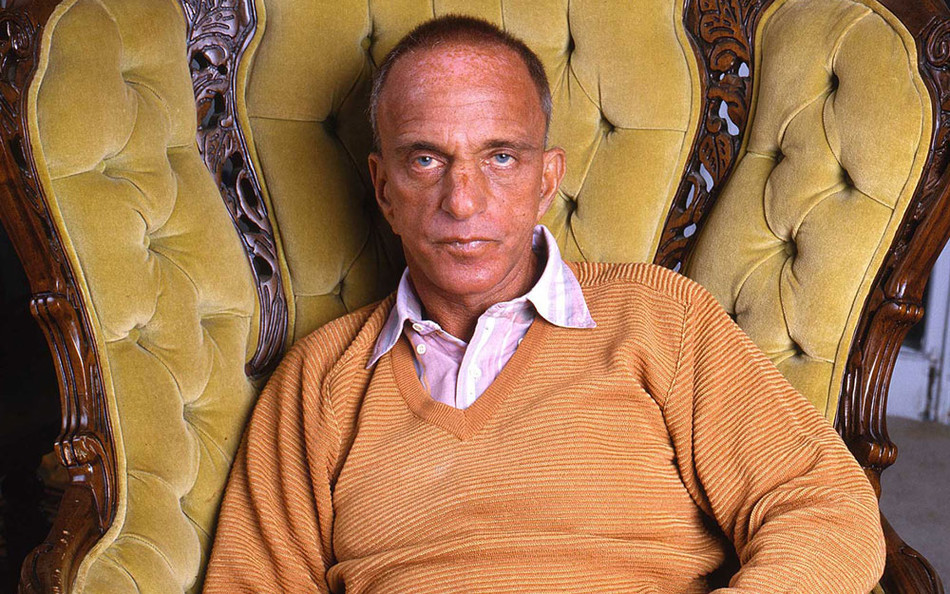

Roy Cohn scares a ghost

Roy Cohn ’46CC, ’47LAW has had a busy afterlife. Best known as the prosecutor who helped send Julius and Ethel Rosenberg to the electric chair for espionage and as the red-baiting chief counsel for Senator Joseph McCarthy during the Army-McCarthy Hearings, Cohn, who died in 1986, has been remembered more recently as a mentor to former president Donald J. Trump, who in 2017, angry at attorney general Jeff Sessions for recusing himself from the Russia investigation, was quoted as saying, “Where’s my Roy Cohn?” Trump’s father, Fred, hired Cohn in 1973 to fight charges brought by the Justice Department that the Trump real-estate business had discriminated against African-Americans.

Cohn’s biggest posthumous role came in the early-1990s Pulitzer Prize–winning play Angels in America, by Tony Kushner ’78CC, ’10HON, in which Cohn is portrayed as an explosive monster of hypocrisy and self-interest. In one scene, Cohn, sick and dying, is visited by the ghost of Ethel Rosenberg:

What is this Ethel, Halloween? You trying to scare me? Well you’re wasting your time! I’m scarier than you any day of the week! So beat it, Ethel! BOOO! BETTER DEAD THAN RED! Somebody trying to shake me up? HAH HAH! From the throne of God in Heaven to the belly of Hell, you can all fuck yourselves and then go jump in the lake because I’M NOT AFRAID OF YOU OR DEATH OR HELL OR ANYTHING!

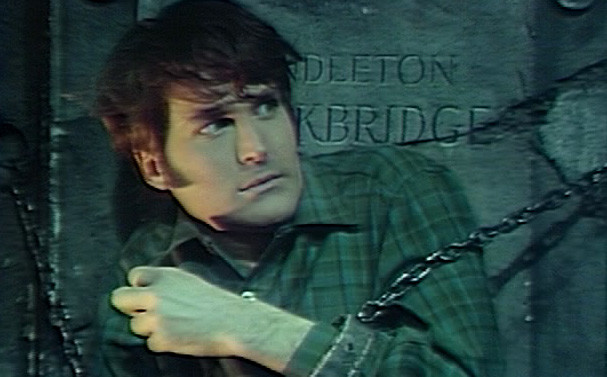

Blood in the afternoon

Vampires aren’t supposed to come out in the daytime, but that’s what happened in 1967 when the gothic soap opera Dark Shadows, which centered on the eerie world of the wealthy Collins family of Collinsport, Maine, introduced the fanged, pallid, cape-draped character of Barnabas Collins. The show doubled down on the scares in 1968, when heartthrob Donald Briscoe ’62CC, ’65GSAS joined the cast, playing five characters, including Chris Jennings, a werewolf. That same year, Roger Davis ’61CC arrived on set, also playing five characters, including a vampire and a lawyer.

Briscoe and Davis had been classmates at Columbia, where they were members of the Columbia Players, the theater group that produced the Varsity Show. Another classmate, who was general manager of the Players, would go on to have a particularly distinguished career in scaring audiences: film director Brian De Palma ’62CC.

Brian De Palma wanted to lend a hand to Carrie

De Palma, a grand master of suspense, started making movies as a Columbia sophomore. “I was with the Columbia Players, and I had a background in photography,” he said in a 1970 interview. “I was obsessed with the idea of directing the Players. But they wouldn’t let undergraduates direct them. So I was frustrated. I figured I’d go out and direct movies instead.”

One of those movies would be Carrie, the 1976 horror masterpiece based on Stephen King's first novel, about a sheltered, awkward, picked-on high-school girl who, when distraught, can move objects with her mind. (Spoilers ahead.) When the shy Carrie, played by Sissy Spacek, is convinced to go to the prom, her life’s sadness turns to unfathomable joy when she is inexplicably chosen to be prom queen. In a virtuoso slow-motion scene of the sort De Palma is known for, Carrie, freshly crowned and basking in applause, is humiliated by her classmates in a cruel prank. Soaked in gleaming pig’s blood, Carrie, without moving a limb, wreaks an elaborate and sadistic vengeance on the entire gymnasium. She then goes home, kills her mother (a ghastly crucifixion involving flying cutlery), destroys the house, and perishes in the inferno.

In the film’s coda, one of the massacre’s traumatized survivors, Sue Snell, played by Amy Irving, has a soft-focus, slow-motion dream in which she brings flowers to Carrie’s grave. As she tenderly places the bouquet down by the wooden cross, a bloody hand shoots up from the dirt and grabs Sue’s arm — a jolt of terror that scared audiences out of their seats in 1976, and still does.

In her autobiography, My Extraordinary Ordinary Life, Spacek takes us behind — and underneath — one of cinema’s most memorable shocks. She recounts how the movie’s art director, Jack Fisk (who was Spacek’s husband), built a wooden chamber underground with a breathing hole and a Styrofoam barrier for Carrie’s arm to thrust through. As Spacek recounts, when she learned that De Palma wanted to hire an extra to do the scene, she objected:

“Please, Brian, I want to do it myself.”

“But Sissy, we’ll have to literally bury you in a coffin in the ground,” Brian said. “Let me hire someone.”

“No, Brian, I do all my own hand and foot work!” I was joking, but I was also serious.

He looked at me and then turned to my husband.

“Jack,” he said. “Bury her.”

A Halloween party for the sages

In his only novel, The Middle of the Journey, about Communism and anti-Communism among a group of American intellectuals, Lionel Trilling ’25CC, ’38GSAS, the literary critic and Columbia professor, based the character of Gifford Maxim on Columbia dropout and Soviet spy Whittaker Chambers. In 1937, Chambers had had a spiritual epiphany: he embraced Christianity, quit the Party, and set about resurrecting his literary career and reputation as a witness to the evils of the Communist enterprise.

In 1938, a year after his conversion, Chambers, hoping to restore his ties with American anti-Stalinist liberals, attended a Halloween party in New York thrown by the Mexican-born intellectual Anita Brenner ’34GSAS. Trilling and his wife, the literary critic Diana Trilling, were there. So was the philosopher Sidney Hook ’27GSAS, who recalled in his 1987 memoir that the arrival of Chambers caused a “sudden hush” to fall over the room. Partygoers were wary of the brilliant, enigmatic, often disheveled Chambers, thinking he might still be a Stalinist spy. Amid decorations of masks, pumpkins, and skeletons, Chambers skulked around the Brenner residence, and Diana Trilling later recalled that more than one guest greeted him with “Whose ghost are you?” According to Hook, “Chambers left with the same fixed and sickly smile on his face with which he entered.”

In 1948, just a year after the publication of Trilling’s novel, Chambers testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), in what proved to be an ideological flashpoint in US cultural and political history. Chambers had accused Alger Hiss, the president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and a former State Department official under Franklin D. Roosevelt ’08HON, of having been a Soviet spy in the 1930s. The Chambers-Hiss hearings captivated the country, and the case turned on a cache of government documents — included materials bearing Hiss’s handwriting — that Chambers had kept hidden inside a pumpkin on his Maryland farm. Diana Trilling would speculate that Chambers got the pumpkin idea from the Halloween decorations at Brenner’s party a decade earlier.

Alger Hiss was convicted of perjury and served forty-four months in prison. Chambers, who died in 1961, worked as a journalist and in 1952 published a memoir, Witness, which became a bestseller. As for Trilling’s novel, reviews were mixed, with critic Irving Howe declaring that the portrayal of Chambers through the character of Maxim was the book’s “one major triumph.”

If Trilling was prescient in anticipating Chambers’s public emergence in 1948, he could hardly have predicted the real-life horror that was to follow: the Chambers-Hiss affair led straight to the McCarthy-led anti-Communist “witch hunts” of the 1950s.

Joseph Mankiewicz had an early thing for ghosts

As a Hollywood director, Joseph Mankiewicz ’28CC, acclaimed for such works as All About Eve, Sleuth, and Suddenly, Last Summer, covered nearly every movie genre. But two of his earliest films were decidedly ghostly: the gothic romance Dragonwyck, which featured a haunted mansion and starred Gene Tierney as an innocent farm girl and Vincent Price as her distant cousin, a creepily charming aristocrat; and The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, again starring Tierney, about a woman who rents a house that is occupied by the ghost of its former owner, a dead sea captain played by Rex Harrison.

Of Dragonwyck, critic Richard Brody of the New Yorker has written, “With its blend of historically accurate political debates and macabre mysteries, it plays like a fusion of Poe and Tocqueville.” Demoncracy in America, anyone?