Amelia Earhart climbed to the top of Low Library

Before becoming an acclaimed aviator and the most famous missing person in the world, Amelia Earhart scaled the heights of Morningside. Earhart attended Columbia from 1919 to 1920 through the Extension Teaching program, which later became the School of General Studies, and returned in the spring of 1925. She planned to matriculate into medical school, but a year later she moved to California to pursue her passion for flying.

While at Columbia, Earhart honed her sense of adventure. In her 1932 memoir, The Fun of It, she recalled, “I was familiar with all the forbidden underground passageways which connected the different buildings of the University. I think I explored every nook and cranny possible” — particularly around Low Library. “I have sat in the lap of the gilded statue which decorates the library steps, and I was probably the most frequent visitor on the top of the library dome. I mean the top.” Several photos of Earhart, taken by her friend and classmate Louise de Schweinitz in 1920, show her perched on the dome’s roof.

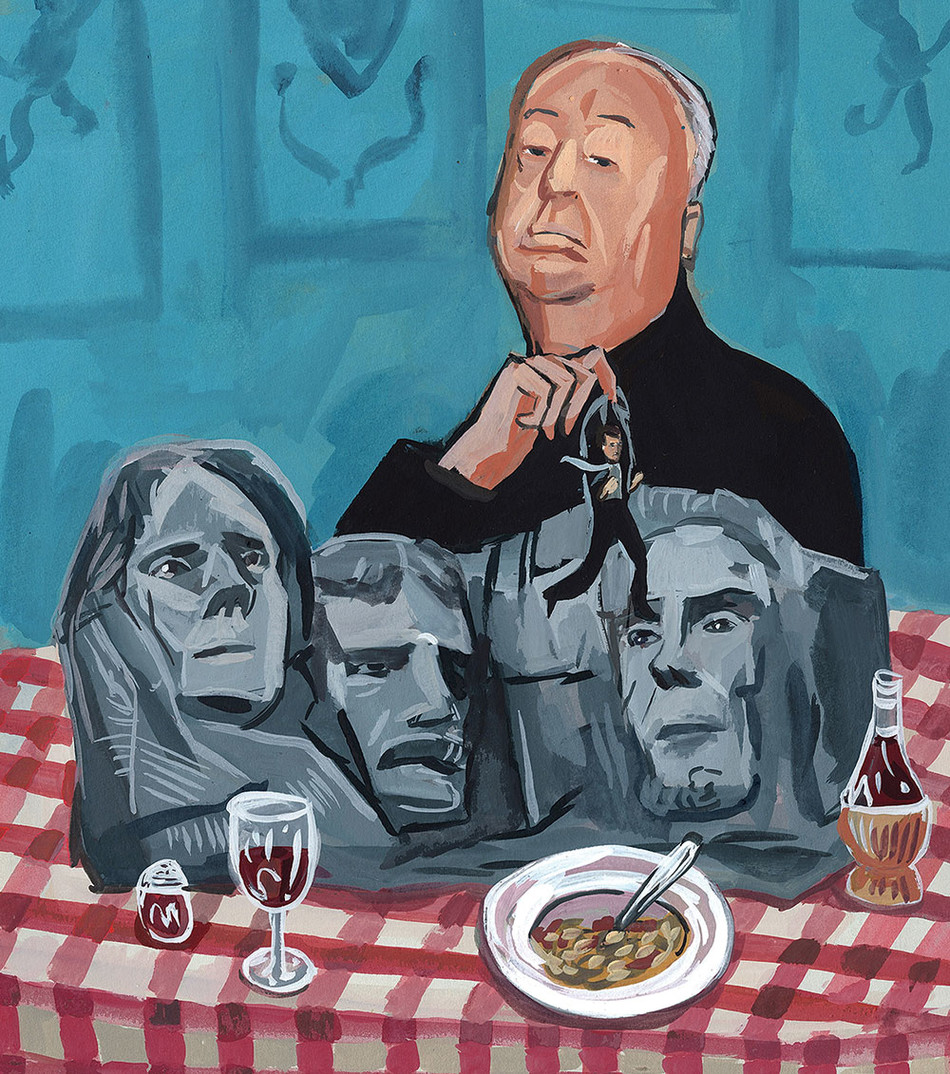

Alfred Hitchcock spilled secrets over lunch

In June 1972, legendary filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock received an honorary degree from Columbia. During his visit, he spoke at the seventy-fourth annual Commencement Day Luncheon in Ferris Booth Hall, sponsored by the Columbia Alumni Federation.

At the luncheon, Hitchcock told guests that during the production of the famous Mount Rushmore scene in the 1959 thriller North by Northwest, he wanted Cary Grant to hide inside Abraham Lincoln’s nostril and have a sneezing fit there. “The parks commission of the Department of the Interior was rather upset at this thought,” the director recalled.

Willa Cather, novelist of the frontier, faced the patriarchy

Willa Cather, the American writer best known for her 1913 novel O Pioneers!, received an honorary degree from Columbia in 1928.

“The Commencement at Columbia was really quite thrilling and splendid,” she wrote to her mother after the ceremony. “I was the only woman among the seven recipients of honorary degrees, the rest were all old men, as you will see by their pictures.” She continued, “I was never so patted and embraced by so many old men at once.”

Cather took note of her popularity: “I really got a great deal more applause than anyone else.” Edith Labaree Lewis, Cather’s domestic partner, was in the audience to watch and cheer. She attested that the roar for Cather lasted twice as long as that for the other recipients.

Cather reported that meeting the Trustees, the professors, and their wives was all very exciting — and exhausting. “I was a tired creature when I came home in President Butler’s car.”

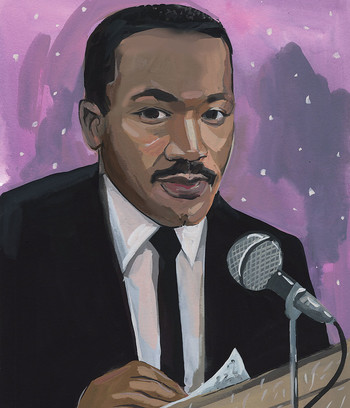

Martin Luther King Jr. headlined a fundraiser organized by a student newspaper

In 1961, The Owl, then the weekly newspaper of the School of General Studies, organized a series of performances by folk singers and comedians to benefit the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). The shows went so well that an SCLC leader in Harlem approached Owl editor Wally Wood and told him that if he could put together a large event, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the chairman of SCLC, would come to Columbia and give a speech.

Wood got to work. He contacted other New York City schools and organized an intercollegiate talk at Columbia’s McMillin Theatre (now Miller Theatre). All the schools sold tickets to ensure a robust, citywide turnout.

On October 27, nearly four hundred people filled the auditorium at Broadway and 116th Street to hear King. “He brought the audience to its feet,” Wood recalls. “The electricity in the room was extraordinary.”

Groucho Marx had a perfectly wonderful evening

During the 1930s, Columbia’s Division of Film Study — one of the first academic cinema-studies departments in the US — hosted the Motion Picture Parade, a series of screenings and panel discussions at Columbia’s McMillin Theatre. Celebrities including Groucho Marx and the director Fritz Lang appeared as speakers.

A pamphlet for the events noted, “The discussion will never be permitted to become hifallutin, arty, or highbrow. It will be kept lively, stimulating, and interesting.”

Bette Davis came for tea and attended an acting class

Two-time Oscar winner Bette Davis made at least two appearances at Columbia over the course of her life.

One occurred in 1929, less than a year before the actress moved to Hollywood to start a screen career. At the time, Davis was starring in Broken Dishes, a Broadway play about a henpecked husband. She and costar Donald Meek, who would later appear in numerous films, including Stagecoach in 1939, were invited to afternoon tea at the Columbia Women’s Graduate Club. As reported in the Spectator at the time, “Miss Bette Davis entertained the group with her interesting reminiscences of her fellow actors.”

In a 1980s interview with biographer Charlotte Chandler, Davis recalled also visiting Columbia with director George Cukor, who had briefly employed her in his theater troupe in the 1920s: “‘It’s important not to have a character indulge in so much self-pity that she loses the sympathy of the audience,’ George Cukor once told me. When I went with him to a Columbia University acting class where he was a guest speaker, he told the young actresses, who were proud of their ability to produce tears, ‘If you cry for yourself, the audience won’t cry for you.’”

W. Somerset Maugham played bridge with President Eisenhower

In 1950, W. Somerset Maugham, the author of The Moon and Sixpence and Of Human Bondage, delivered a lecture at Columbia at the invitation of a friend, the philosopher Irwin Edman 1917CC, 1920GSAS. According to the biography Maugham, by Ted Morgan ’55JRN, the room had no microphone and was “unseasonably warm,” so windows were open and Maugham had to compete with noise from the street outside.

The next day, the novelist played bridge with Columbia president Dwight Eisenhower ’47HON, where he reportedly lost twelve dollars and was a sore loser. But he would later say, “We had a very agreeable game.”

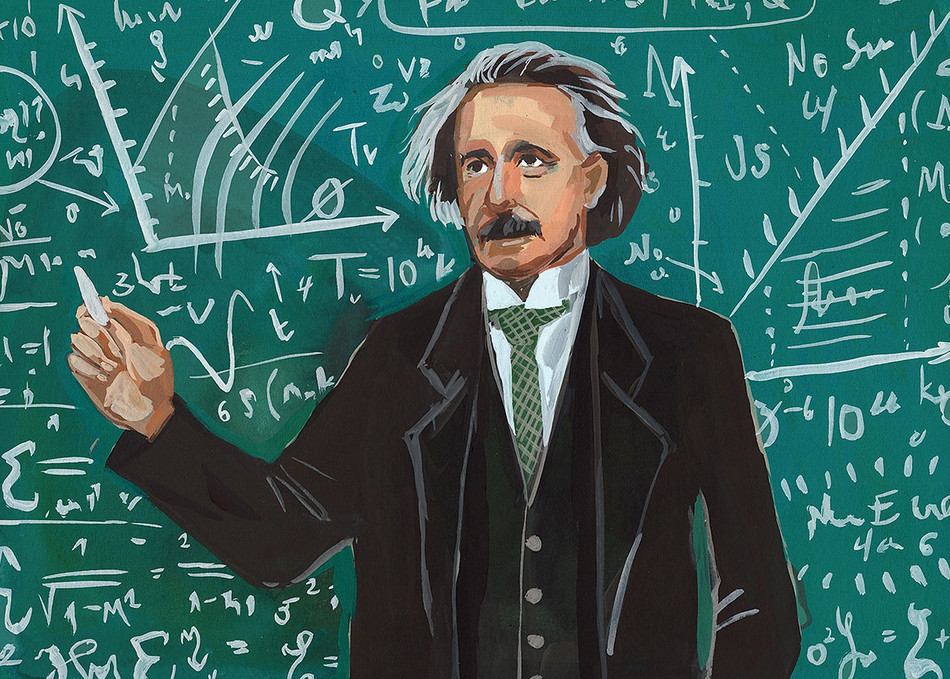

Albert Einstein gave a relatively simple presentation

In 1921, Albert Einstein gave his first public lecture in the United States on the theory of relativity. The speech, which he delivered in German, took place at the Horace Mann Auditorium at Columbia Teachers College.

The Spectator reported that the small number of attendees who understood Einstein’s native language laughed when the scientist related that parts of his theory were really “very simple.”

According to the New York Times, Einstein also “caused much amusement when he wished to erase diagrams he had drawn on the blackboard and made futile motions in the air with his hand until Professor [Michael] Pupin came to his rescue” with an eraser.

Federico García Lorca mingled at campus parties

Spanish poet Federico García Lorca spent ten months in New York City from 1929 to 1930. During his stay, he took English classes at Columbia, lived on campus in Furnald and John Jay Halls, and wrote his book Poet in New York on University stationery. He was struck by the city’s intense social environment. “There are more parties and gatherings here than anyplace else in the world,” he wrote to his family back home. “Americans cannot stand to be alone.”

Reflecting on the University, he wrote, “I have never seen more innocent creatures in my life than these Columbia students, or kinder, or more savage ones. This is a totally savage people, perhaps because there is no class system. These boys stretch and yawn with the innocence of animals, they sneeze without taking out their handkerchiefs and are always shouting, everywhere.”

He added, “And yet they are open and friendly, and they truly enjoy doing a favor for you.”

Édith Piaf showed off her pipes

Known as la môme piaf, or the little sparrow, Édith Piaf rose to fame in the 1940s with her international hit “La Vie en Rose.” During her first trip to the United States, in 1947, the petite chanteuse visited the Maison Française at Columbia and took English lessons from Maison director Eugene Sheffer ’26CC.

During her time at the Maison, Piaf gave a concert that the Spectator called “brilliant” and that “left applause ringing in her ears long after she had concluded.” Piaf and Sheffer became lifelong friends.

Roar-ee inspired the MGM lion

Before Howard Dietz became a prolific lyricist of Broadway musicals such as 1931’s The Band Wagon, he worked as an adman in the late 1910s at the Philip Goodman Agency. One of his clients was movie mogul Samuel Goldwyn, whose new production studio, Goldwyn Pictures Corporation, needed a logo.

Having recently dropped out of Columbia Journalism School, the young Dietz was inspired by Columbia’s mascot — specifically, the laughing lion seen in the campus humor magazine The Jester — and proposed that Goldwyn’s company use a roaring lion for its own branding. Leo the Lion was born; Dietz was hired as Goldwyn’s director of advertising and publicity; and the company, which became known as Metro Goldwyn Mayer after a 1924 merger, went on to become one of Hollywood’s “big five” studios.

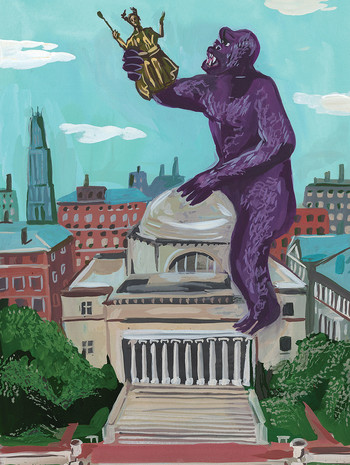

King Kong’s codirector learned moviemaking here

One of the most iconic film scenes of all time involves a giant ape perched atop the Empire State Building, swatting at airplanes attempting to shoot the creature down.

Ernest B. Schoedsack, codirector of the 1933 film King Kong and the sole director of its sequel Son of Kong, learned how to shoot action scenes at Columbia, but not in a traditional film-production program.

In January 1918, Columbia had opened the School of Military Cinematography to train World War I soldiers in combat photography and filmmaking. Organized by the US Army through an arrangement with University president Nicholas Murray Butler, the school hired such up-and-coming faculty as Victor Fleming, who would later direct the 1939 classics The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind.

It was in the Columbia program that Schoedsack, who went on to document the Polish–Soviet and Greco–Turkish wars for the American Red Cross, studied the art of combat film. (Ape bombardment was not part of the curriculum.)

Winston Churchill paid a warm tribute to Nicholas Murray Butler

In March 1946, six months after the formal end of World War II, Winston Churchill took an extended trip across the pond. During his stay, he gave his famous Iron Curtain speech at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, before accepting an honorary degree from Columbia.

Approximately eleven thousand people — including several hundred picketers protesting the threat of a new war with the USSR — crowded outside Low Library to greet the former British prime minister. While speaking in the library’s rotunda, Churchill paid tribute to his longtime friend Nicholas Murray Butler 1882CC, 1884GSAS, who had just retired as president of Columbia and had recently gone blind. Churchill told the audience, “The light that burns within burns all the brighter.”

Paul Robeson fell in love and switched careers

In 1920, before he became an international star of stage and screen and shortly after he distinguished himself as an All-American football player at Rutgers, Paul Robeson ’23LAW was a law student at Columbia. To support himself he played professional football. One day Robeson got injured during a game and was taken to Columbia Presbyterian Hospital, where he stayed for weeks.

At least one hospital worker recognized him. Eslanda “Essie” Cardozo Goode 1920TC, a chemist in the pathology lab — the first Black person to be hired there — had met Robeson in Harlem. Now she had the chance to get to know him better. They fell in love, and Goode, who would become an anthropologist, journalist, and civil-rights activist, as well as Robeson’s business manager, persuaded the then-unknown performer to accept the lead role in a play at the Harlem YMCA called Simon the Cyrenian, about an Ethiopian man who helps Jesus carry his cross. Robeson’s performances were electric, and word got out.

In 1921, Robeson and Goode eloped, and after graduating from Columbia, Robeson joined an all-white law firm, only to quit after a secretary refused to take his dictation. Disgusted, he turned his back on the profession — a foreshadowing of the public stance against racism that would define his legacy.

With Essie Goode Robeson’s encouragement, Paul Robeson returned to the stage, playing the leads in Eugene O’Neill’s All God’s Chillun Got Wings and The Emperor Jones, and in 1936 he starred in the film version of Show Boat, in which he sang “Ol’ Man River.” The following decade he played the title role in Othello, which ran for 296 performances — still the longest-running Shakespeare play in Broadway history.

The Grateful Dead sneaked onto campus

On May 3, 1968, more than a week into the student protests that rocked Columbia, iconoclastic hippie band the Grateful Dead played a surprise show outside Ferris Booth Hall. Because police had barricaded campus, the group’s six members and their instruments had to be smuggled through Columbia’s iron gates in a bread delivery truck.

“Always up for an adventure, we of course went right along,” recalled drummer Mickey Hart. “We were already jamming away before the security and police could stop us.” Bass guitarist Phil Lesh remembers it as being “the fastest setup ever.” In his memoir, Searching for the Sound: My Life with the Grateful Dead, he writes, “We play a short set, pack up, and split — the whole operation taking less than two hours.”