Hot Weather Is More Dangerous than You Think. Here Are 6 Things You Need to Know

As global temperatures continue to rise, heat stroke, once rare, is now the leading weather-related killer in the US, responsible for hundreds of deaths per year. But misconceptions about this serious condition and other forms of heat illness, like heat exhaustion, are pervasive.

“Even healthcare professionals are having to educate ourselves about heat illness, because in recent years scientific understanding of the threat has evolved as heat waves have become more frequent, intense, and long-lasting,” says Christopher Tedeschi, an emergency physician at Columbia University Irving Medical Center (CUIMC) and an expert on how extreme heat affects the human body.

Columbia Magazine recently spoke to Tedeschi, who oversees the emergency department’s preparedness for mass casualty events, about the basics of heat illness, how to prevent it, and when to seek medical care. Here’s what we learned.

No one is immune to heat illness, and older adults, and kids, are particularly vulnerable

Heat illness, which occurs when the body builds up more heat than it can dissipate, can affect anyone exerting themselves in hot weather or exposed to high temperatures for long periods of time, according to Tedeschi. But older adults, young children, athletes, people working outdoors, and those living in urban “heat islands” that lack cooling trees and green spaces are especially vulnerable. “I worry a lot about people over 65 because as we age our bodies have a more difficult time regulating temperature,” says Tedeschi, who notes that many medications commonly taken by older adults, including diuretics, can interfere with the body’s ability to cool itself. He adds that children’s bodies heat up very quickly because they have more surface area relative to their mass. “The big challenge with kids is they’re not as good at articulating what they’re physically feeling, so if heat illness is coming on, they may simply act cranky and irritable or seem to have an upset stomach. Parents and doctors need to be attentive to the signs of heat-related illness.”

Heat stroke is very different from heat exhaustion

The most common form of heat illness, heat exhaustion, is a fairly mild ailment marked by dizziness, headache, nausea, and vomiting. A person will feel uncomfortably hot, as a result of their body surface temperature rising, but their core temperature will remain stable and their symptoms will typically resolve after they rest, hydrate, and cool off.

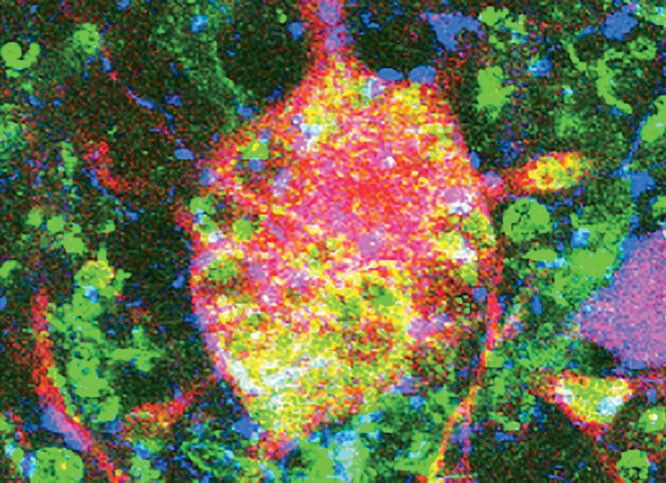

Heat stroke, on the other hand, is a life-threatening condition that occurs when the temperature of one’s internal organs exceeds 104°F. In addition to physical weakness, it causes confusion, delirium, loss of consciousness, seizures and other neurological symptoms and can prove deadly if a person isn’t treated promptly. “It can be tricky to spot at first because its neurological symptoms resemble those of other conditions, including cerebral strokes,” says Tedeschi. “Once a person is determined to have heat stroke, we’ll immerse them in ice water until their core temperature drops back down into the normal range.” He says that during heat waves CUIMC doctors keep coolers filled with ice for this purpose. “Then we’ll monitor the patient to make sure the heat stroke hasn’t sparked any other problems.”

Seek medical attention for heat stroke, no matter what

If you suspect that you or someone in your company is experiencing heat stroke — with cognitive difficulties being the surest indication — get medical attention immediately, because delaying treatment can have long-term health consequences, according to Tedeschi. “A spike in core body temperature can stress the heart and cause lasting damage to the kidneys, liver, and other organs,” he says. “The longer treatment is delayed, the greater these risks.”

Tedeschi says it’s a good idea to seek medical attention for heat exhaustion, too, especially if you are older or have existing medical issues. “Even mild heat illness can exacerbate other conditions including cardiovascular and lung disease,” he says. “So, if you’ve overheated and attempted to cool off, but still don’t feel well after a little while, go to the hospital. On the way, you can continue to cool down using ice packs or wet towels.”

When the mercury rises, don’t go solo

On sweltering days, avoid engaging in strenuous activities by yourself or in desolate locations because if you develop heat stroke you may become disoriented and struggle to get help, Tedeschi says. “Preparation and prevention are extremely important, given the cognitive symptoms that can occur,” he says. “I tell people to stick together, and before you head out on that jog or hike, talk about the warning signs of heat illness. And then pay attention to how people are doing around you. If someone looks really wiped out, have the confidence to say, ‘Hey, why don’t we sit down for a minute? Why don’t we take a dip and cool off?”

Similarly, primary-care physicians, athletic coaches, employers, and others need to educate themselves about the dangers of heat illness and promote awareness among those whose safety they are entrusted with. “Simply encouraging people to stay hydrated, take breaks to cool off, and ask for help if they feel too hot can save lives,” he says.

Temperatures don’t need to be exceptionally high to pose a danger

When planning activities, pay attention not only to the temperature but to the “heat index,” which describes the cumulative impact of heat and humidity. “Your body naturally cools itself by perspiring, but when it is extremely humid outside the perspiration cannot evaporate off your skin and so you can’t cool down,” Tedeschi says. “The difference this makes can be enormous.” For example, he notes that a 90-degree day with 75-degree humidity will feel, to the human body, like 110 degrees.

There’s no substitute for cooling off

“One of the myths about heat illness is that you can ward it off merely by staying hydrated,” Tedeschi says. “But that’s not true. Hydration is necessary, but not sufficient, for preventing and treating heat illness. Think about a football player who collapses at practice on a 90-degree day — that guy was probably drinking lots of Gatorade. The problem is that he’s too hot despite it. So, he needs to be taken inside to cool off. There’s no substitute for that.”